It’s a testament to the wide-ranging and unconventional nature of Joseph Priestley’s mind that no one has settled on a term to sum up exactly what he was. The eighteenth-century British polymath has been described as, among other things, a historian, a chemist, an educator, a philosopher, a theologian, and a political radical who became, for a period of time, the most despised person in England. Priestley’s many contradictions—as a rationalist Unitarian millenarian, as a mild-mannered controversialist, as a thinker who was both ahead of his time and behind it—have provided endless fodder for the historians who have debated the precise nature of his legacy and his place among his fellow Enlightenment intellectuals. But his contributions—however they are categorized—have continued to live on in subtle and surprisingly enduring ways, more than two hundred years after his death, at the age of seventy, in rural Pennsylvania.

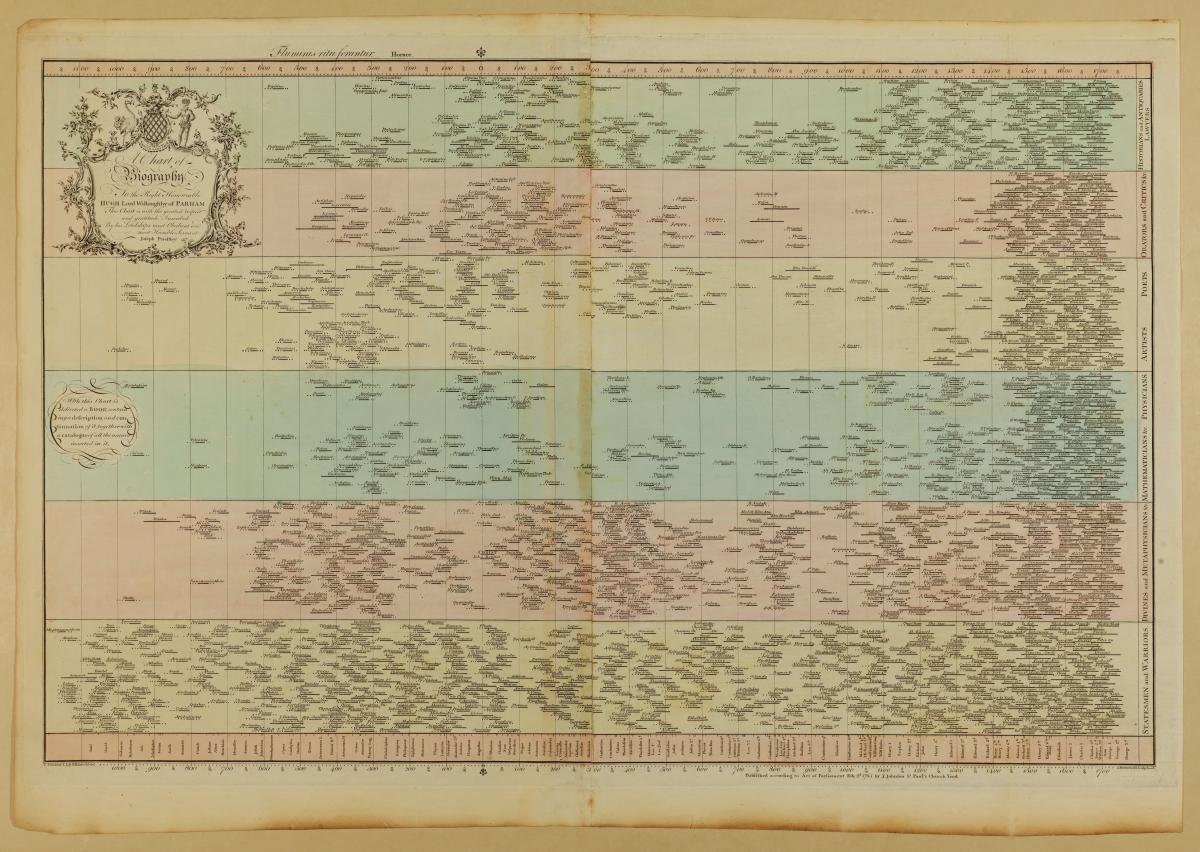

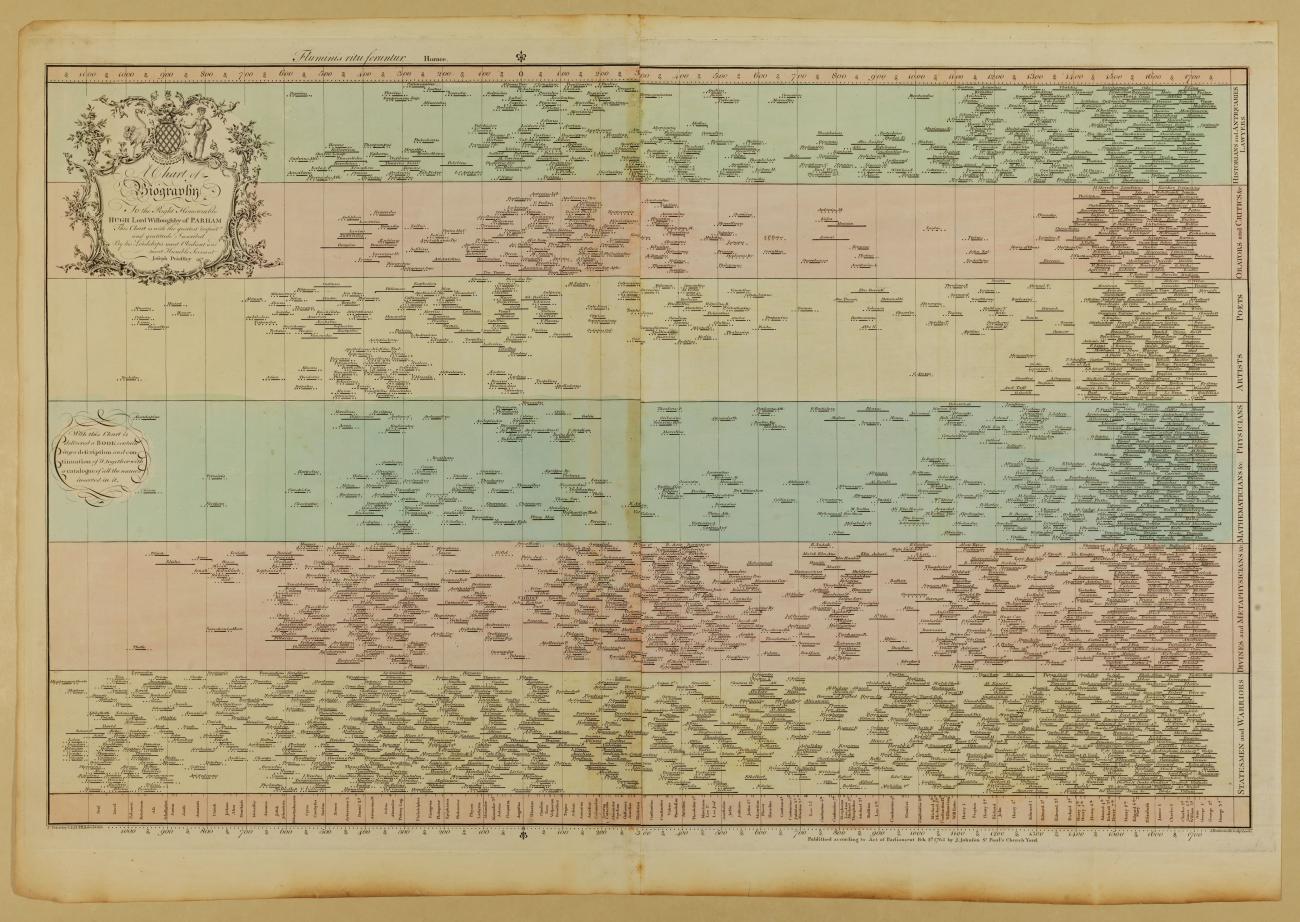

Take, for example, A Chart of Biography, which is considered to be the first modern timeline. This unusual, and unusually beautiful, pedagogical tool, which was published by Priestley in 1765, while he was in his thirties and working as a tutor at an academy in Warrington, England, tends to get lost in the shuffle of Priestley’s more notable achievements—his seminal 1761 textbook on language, The Rudiments of English Grammar, say, or his discovery of nine gases, including oxygen, 13 years later. But the chart, along with its companion, A New Chart of History, which Priestley published four years later, has become a curious subject of interest among data visualization aficionados who have analyzed its revolutionary design in academic papers and added it to Internet lists of notable infographics. Recently, both charts have become the focus of an NEH-supported digital humanities project, Chronographics: The Time Charts of Joseph Priestley, produced by scholars at the University of Oregon.

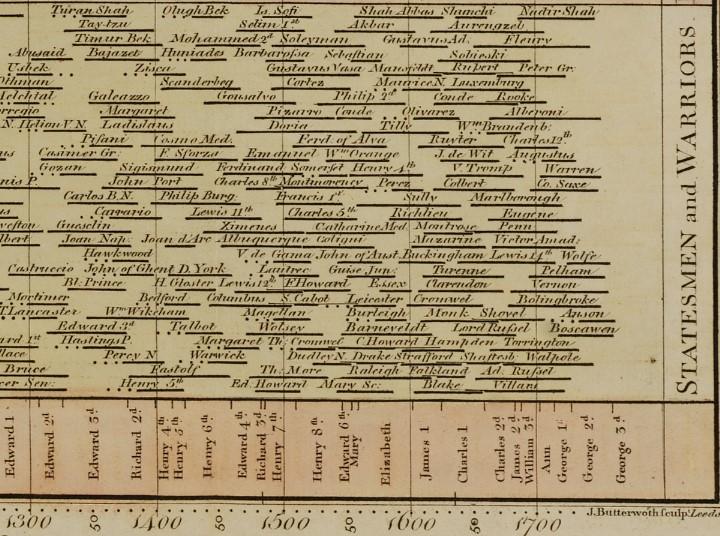

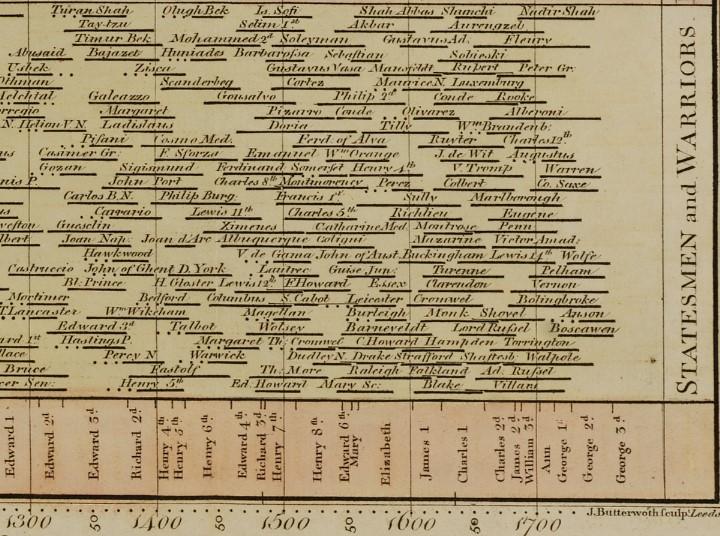

Even those of us ignorant of (or uninterested in) infographics can look at the painstakingly detailed Chart of Biography for a moment or two and appreciate how it has become a source of fascination. The two-foot-by-three-foot, pastel-striped paper scroll—which contains the meticulously inscribed names of approximately 2,000 poets, artists, statesmen, and other famous historical figures dating back three millennia—is visually striking, combining a formal, somewhat ornate eighteenth-century aesthetic with the precise organization of a schematic. Every single one of the chart’s subjects is grouped vertically into one of six occupational categories, then plotted out chronologically along a horizonal line divided into ten-year increments. Despite the huge quantity of information it contains, it is extremely user-friendly. Any one of Priestley’s history students could run his eye across the chart and immediately gain a sense of the temporal lay of the land. Who came first: Copernicus or Newton? How many centuries separate Genghis Khan from Joan of Arc? Which artists were working during the reign of Henry VIII? The chart was a masterful blend of form and function, and Priestley knew it.

“Please now to inspect the Chart, and as soon as you have found the names, you see at one glance, without the help of Arithmetic, or even of words, and in the most clear and perfect manner possible, the relation of these lives to one another in any period of the whole course of them,” he boasted.

The most significant design feature of Priestley’s chart—as historians point out—was the way in which he linked units of time to units of distance on the page, similar to the way a cartographer uses scale when creating a map. (The artist Pietro Lorenzetti lived two hundred years before Titian and thus is situated twice as far from Titian as Jan van Eyck, who predated Titian by about a century.) If this innovation is hard for contemporary viewers to fully appreciate, it’s probably because Priestley’s representation of time has become a convention that’s used everywhere in visual design and seems so obvious it’s now taken for granted.

To Priestley’s contemporaries, though, who were accustomed to cumbersome Eusebian-style chronological tables or the visually striking but often obscure “stream charts” created by the era’s chronographers, Priestley’s method of capturing time on the page revealed something revelatory and new—a way of seeing historical patterns and connections that would have otherwise remained hidden. “To many readers,” wrote Daniel Rosenberg and Anthony Grafton in their book, Cartographies of Time, Priestley’s Chart of Biography offered a never-before-seen “picture of time itself.”

It was no wonder, then, that eighteenth-century readers found themselves drawn to it. A Chart of Biography sold well in both England and the United States, accruing many fans along the way. Along with the New Chart of History, it would go on to be printed in at least 19 editions and spawn numerous imitations, including one by Priestley’s future friend Thomas Jefferson, who developed his own “time chart” of market seasons in Washington, and the historian David Ramsay, who acknowledged Priestley’s influence in his Historical and Biographical Chart of the United States. The time charts marked Priestley’s first major commercial success and played a key role in establishing his reputation as a serious intellectual, earning him an honorary degree from the University of Edinburgh, and helping him secure a fellowship nomination to the Royal Society of London.

As much as anything he published, and he published a staggering amount—somewhere between 150 and 200 books, articles, papers, and pamphlets—Priestley’s time charts encapsulate his uniqueness as a thinker. Of his many intellectual gifts, his gift for synthesis—for knitting together the seemingly disparate things that caught his attention—might have been his greatest. On any given subject, his biographer Robert Schofield observed, Priestley had “contemporaries who were more profound and analytic,” but he “made systematic and operational what had been fragmentary, frequently impractical, and unused before him.”

The charts, which he energetically promoted, also serve as a perfect example of the man’s seemingly compulsive need to share the knowledge he acquired with others. “The proper employment of men of letters,” he once wrote, “is either making new discoveries, in order to extend the bounds of human knowledge; or facilitating the communication of the discoveries which have been made already, in order to make an acquaintance with science more general among mankind.”

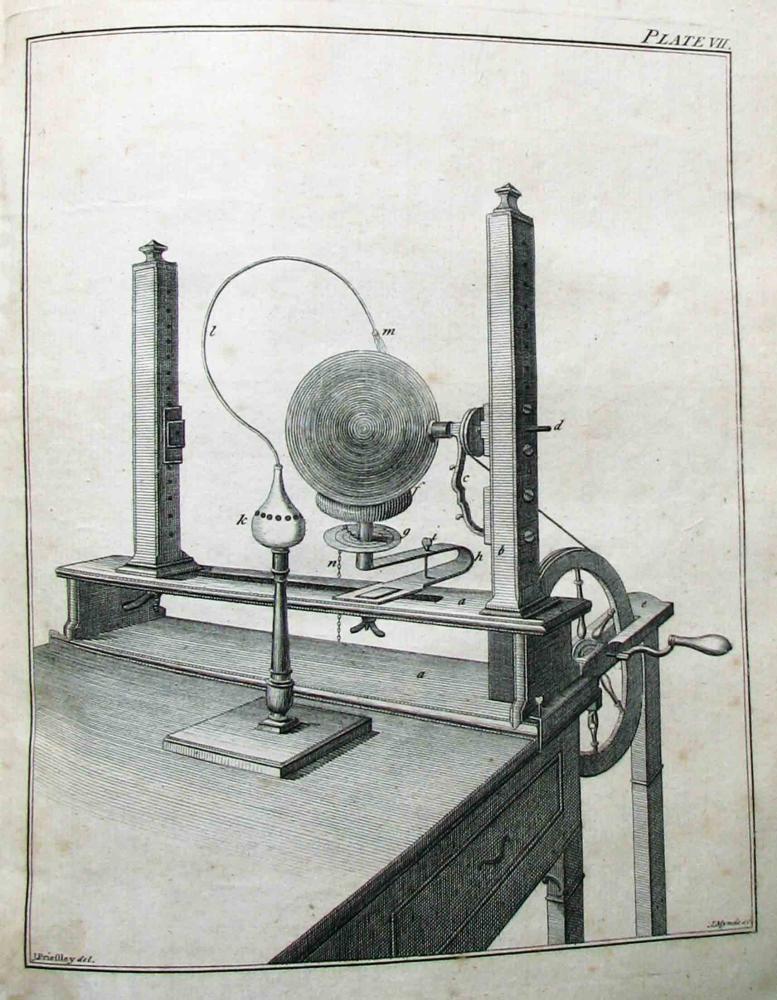

In this regard, he wholeheartedly practiced what he preached. After Benjamin Franklin’s 1751 book on electricity piqued his interested in the subject, Priestley finagled an introduction to the book’s famous author, then proceeded to research and publish his own 700-page tome on the subject—a “history of the discoveries in electricity,” complete with his own experiments for interested readers. When the book’s plates required an illustrator, and he was unable to find a satisfactory one, he taught himself perspective drawing, then published a 1770 tutorial for aspiring artists titled A Familiar Introduction to the Theory and Practice of Perspective. (Fun fact: Priestley is often credited with discovering the erasing properties of rubber, as well as with naming the substance, which was perfectly suited for “rubbing” away errant pencil marks.)

A bit of dabbling in the subject of optics followed, along with a history of the field, published in 1772. That same year, after explaining to friends over dinner one night how he could “sweeten” water by using a pig’s bladder to infuse it with carbon dioxide, he produced the 34-page illustrated pamphlet “Directions for Impregnating Water with Fixed Air.” “To make this process more generally known,” he wrote in its preface, “and that more frequent trials may be made of water thus medicated, at land as well as at sea, I have been induced to make the present publication.”

Priestley’s “Pyrmont water”—or what’s commonly known today as carbonated water—was an instant hit in England and France and contributed to his receiving the Copley Medal of the Royal Society in 1773. Bolstered by the mistaken belief that the water contained antiscorbutic properties, Britain’s Royal College of Physicians instructed Captain James Cook to test out the carbonation process on his upcoming second sea voyage. Regardless of whether Cook actually carried out the experiment—sources conflict on this point—it was doomed to failure. Priestley’s fizzy Pyrmont water had no more vitamin C in it than uncarbonated flat water, and so it was equally useless when it came to preventing scurvy. But it was an unconventional, and thus fitting, way to mark Priestley’s foray into yet another scientific discipline. Schofield noted wryly: “This is the work for which Priestley became known to the world as a chemist; a description of how to make ‘soda water,’ wrongly assumed to have medicinal value.”

Priestley turns up in another intriguing footnote related to Cook’s famous 1772 voyage—which is that he was, briefly, offered the opportunity to join the expedition as one of the ship’s astronomers. The invitation, which was extended to Priestley in a letter from the legendary botanist Joseph Banks, is the kind of tantalizing “what if” that counterfactual history is made from. Who knows what other subjects Priestley would have set his sights on if he’d had the opportunity to travel the globe?

A few weeks after receiving Banks’s invitation, the offer was rescinded. The reason was never fully made clear, but Priestley had a theory. “Mr. Banks,” he would write in a memoir that was published two years after his death, “informed me that I had been objected to by some clergymen . . . on account of my religious principles.”

This may or may not have actually been the case. (Schofield contends that Banks jumped the gun, inviting Priestley to join the expedition without being authorized to do so.) But Priestley’s assumption was an understandable one. He was a nonconformist minister and a member of England’s Protestant Dissenter minority, one that opposed state involvement in religious issues, refused to subscribe to the Anglican church’s doctrine, and, as result, faced discrimination. (Dissenters like Priestley were, for instance, prohibited from matriculating at the University of Oxford or Cambridge until the nineteenth century.)

And Priestley’s heterodox religious views were a matter of public record. He was, by that point, a seasoned veteran of the era’s pamphlet wars, having embroiled himself in controversy with his 1768 A Free Address to Protestant Dissenters on the Subject of the Lord’s Supper before going on, two years later, to attack major aspects of Calvinist doctrine in An Appeal to the Serious and Candid Professors of Christianity. Over the next two decades, his notoriety would only grow as he published a series of “brilliantly controversial works,” wrote the historian David Wykes, which “advanc[ed] ideas that caught up and convinced many of his readers and a generation of young ministers” but which also unleashed “a storm of anger.” Orthodox readers were not particularly keen to hear Priestley analyze the logical flaws he had discovered in the doctrine of atonement or to hear him out as he explained the ways in which their beliefs regarding the Holy Trinity were “inconsistent with reason and common sense.” In 1785, three years after it was published, his book An History of the Corruptions of Christianity was banned in Holland.

Far from silencing him, the barrage of angry responses goaded Priestley into picking up his pen and producing more pamphlets filled with more arguments. “He entered each controversy with a cheerful conviction that he was right, while most of his opponents were convinced, from the outset, that he was willfully and maliciously wrong,” Schofield wrote. “He was able, then, to contrast his sweet reasonableness to their personal rancor while responding, in kind to irony and sarcasm.”

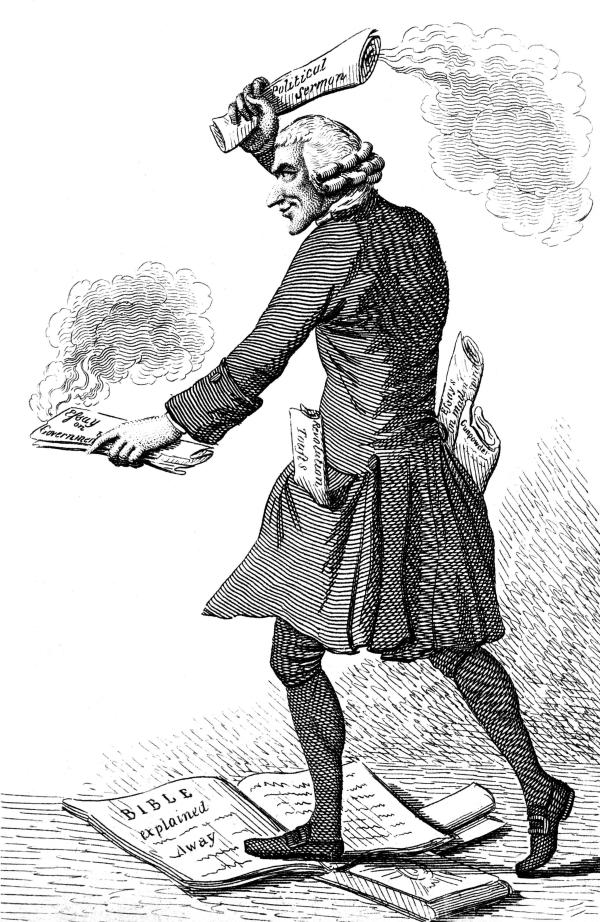

Priestley’s religious provocations, combined with a potent mix of unpopular political views—his support for the American and French revolutions, his criticism of the slave trade, his commitment to religious liberty for Dissenters, his agitation for parliamentary reform—only served to cement his reputation, first as a radical, and then as a dangerous menace. By 1790, his enemies had come to see the soft-spoken minister as “the devil incarnate,” wrote Wykes. It was a comparison that Priestley, perhaps unwisely, did not shy away from. “If he really took me to be that malicious Being, above described,” he wrote gleefully of one of his foes, “he should not have trodden upon my cloven foot, or have kicked me so near my tail, without remembering that I had horns, and he had none.”

Had he known what was coming, he might not have found it so amusing. One evening in the following July, Priestley received a warning that a large number of protestors had attacked a group of diners attending a Bastille Day celebration at the Birmingham Hotel. From there, the mob—which had grown significantly larger—moved on to destroy the Unitarian meeting house where Priestley presided as minister, ripping out the pews and setting them on fire. And, it seemed, they were now on their way to the Priestley residence. There was no time for Priestley and his wife to do anything but flee, and then watch as a crowd converged on their house and proceeded, with some difficulty, to burn it to the ground. “It being a remarkably calm, and clear moon-light,” Priestley recalled later:

We could see to a considerable distance, and being upon a rising ground, we distinctly heard all that passed at the house, every shout of the mob, and almost every stroke of the instruments they had provided for breaking the doors and the furniture. For they could not get any fire, though one of them was heard to offer two guineas for a lighted candle; my son, whom we had left behind us, having taken the precaution to put out all the fires in the house, and others of my friends got all the neighbours to do the same. I afterwards heard that much pains was taken, but without effect, to get fire from my large electrical machine, which stood in the library.

The attack on Priestley was personal—but it also wasn’t. Over the next several days, widespread terror and looting would engulf Birmingham as rioters clashed with local constables, targeting and destroying some two dozen homes, businesses, and churches belonging to prominent Dissenters and supporters of the French Revolution before authorities finally called in military dragoons to restore order. In the end, the violent events of July 1791 would come to be known as the Priestley riots, after their most high-profile victim, and the man who symbolized everything his “Church and King” enemies despised.

On one of Priestley’s sweeping timelines, a few days of riots would not merit even a speck of ink. As a historian, Priestley was well aware of this fact. More than two decades earlier, long before his home and nearly all his worldly possessions were destroyed, he had studied the rise and fall of empires, mapped out across his New Chart of History, and attempted to counsel his readers about the lessons he had found there. “What a number of revolutions are marked upon it!” he wrote:

What torrents of human blood has the restless ambition of mortals shed, and in what complicated distress has the discontent of powerful individuals involved a great part of their species! Let us deplore this depravity of human passions . . . but let not the dark strokes which disfigure the fair face of an historical chart affect our faith in the great and comfortable doctrine of an over-ruling Providence.

In the weeks and months following the riots, this sense of perspective would be put to the test. The mob had destroyed not only Priestley’s home, his valuable collection of manuscripts, and his beloved, expensive lab equipment (worth around $115,000 in today’s dollars), but also whatever illusions he might once have harbored about his own safety. Far from cooling the depraved human passions against him, the historian Wykes wrote, the events in Birmingham had turned him into “a national figure of hate.”

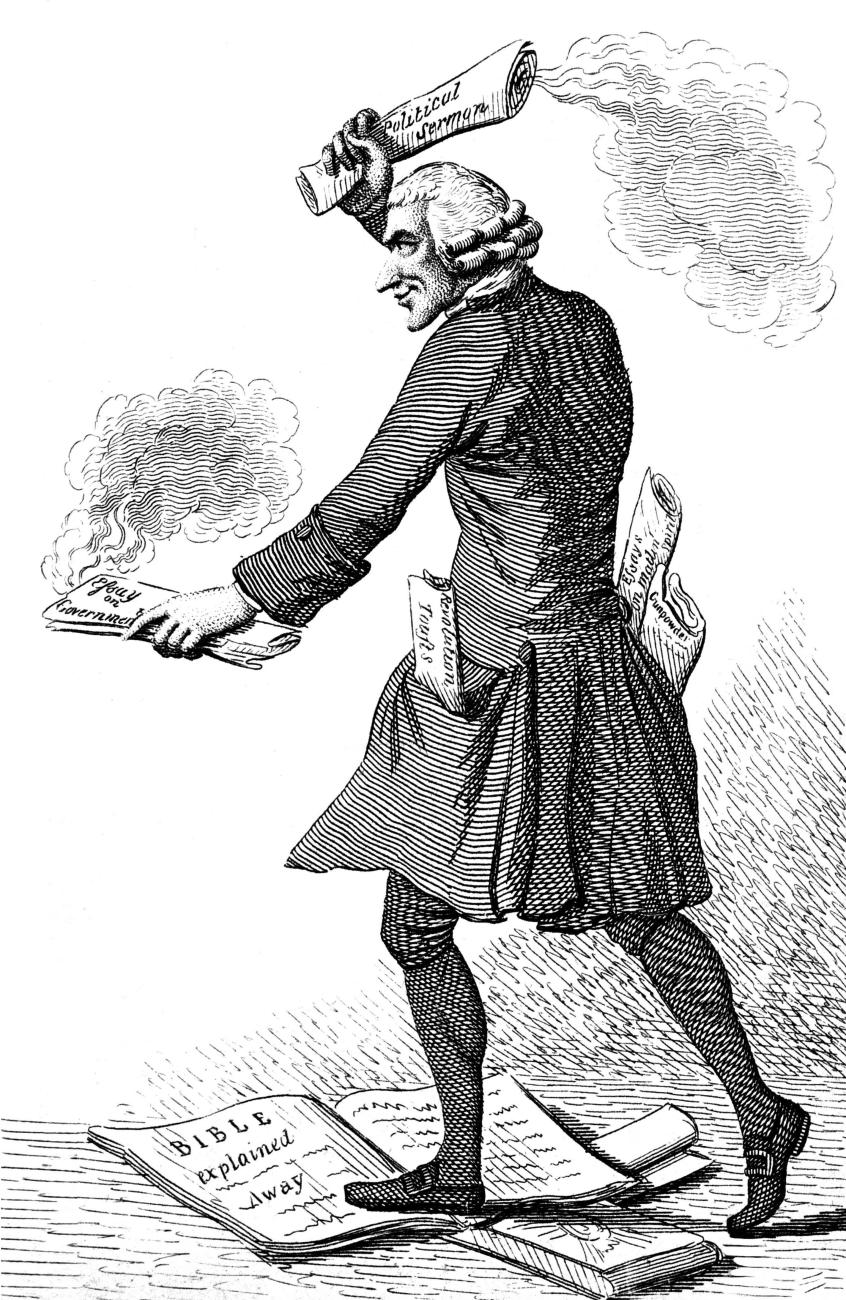

Priestley was satirized in caricatures, burned in effigies with his fellow radical, Thomas Paine. His adult sons were forced to flee the country. The prosecutions of fellow Dissenters that followed over the next few years were particularly frightening. “It shews that no man who is obnoxious,” he fretted in a 1793 letter, “however innocent, is safe.” And so, the following spring, at the age of sixty-one, he became a political refugee, following his sons Joseph and Harry across the Atlantic, where he was met with a hero’s welcome in the United States, eventually settling down with his family in the small town of Northumberland, one hundred forty miles northwest of Philadelphia, to assume the quiet life of a farmer.

But farming didn’t suit Priestley and neither did quiet. Over the next several years, Priestley found himself back in political hot water, clashing this time with his friend John Adams and the Federalists, in danger, at one point, of being deported from the very country that had just offered him asylum. (Adams blamed Priestley’s Letters to the Inhabitants of Northumberland for contributing to his 1800 electoral defeat to Jefferson.) In his adopted homeland, Priestley returned to his scientific work with renewed zeal, but that, too, proved to be controversial, as he produced paper after paper attacking the experiments of his fellow chemists, who had moved on from Priestley’s outdated theory of “dephlogisticated air” to follow the more quantitative approach of scientists like Antoine Lavoisier. In doing so, Schofield observed, Priestley was “perversely fighting the new chemistry based on his discoveries” in a way that would come to exasperate even his admirers. In a eulogy written for the Académie Nationale des Sciences, the zoologist Georges Cuvier would famously proclaim Priestley to be “the father of modern chemistry [who] never acknowledged his daughter.”

The century-old theory Priestley relied upon during his pneumatic experiments—which postulated that all flammable substances contained an element called phlogiston that was released into the surrounding air during combustion—proved to be wrong in the end. But the work he conducted in the final decade of his life was not a wasted effort, says Schofield. By relentlessly hounding his critics, by probing for the weak spots in their arguments, he had “forced the tightening of their experimental evidence,” and compelled them to up their scientific game. Surely that fact would have offered him some satisfaction. He understood that the pursuit of knowledge was not a solitary one. Even the most famous individuals, the ones whose accomplishments fill the pages of books, the ones whose names adorn charts of history, he once wrote, “enjoy . . . the labours and discoveries of others” before they “go off the stage,” leaving their work behind, to be advanced by those who follow them.

Priestley labored as long as possible, through deteriorating health and advancing old age, continuing to conduct experiments until he was unable to leave his bed. On February 6, 1804, he called his assistant to his side with one final request for help on revisions to an unfinished manuscript that required his attention. He worked until he had assured himself that he had finished what was needed. “That is right,” he said. “I have now done.” Minutes later, he was gone.