It was “the locus of mad freedoms.”

That’s how the painter David X. Young once described the “Sixth Avenue Loft,” a grungy, vermin-infested, five-story walk-up at 821 Sixth Avenue in New York City’s Flower District that served as Young’s art studio and home from 1954 to 1964. How we know anything about what happened there, especially its place in the history of jazz music, is an “accident of history,” according to Sam Stephenson, author of The Jazz Loft Project. What we know is the result of one man’s compulsive need to document the world around him: American photographer W. Eugene Smith.

Today, 821 Avenue of the Americas reveals nothing of its past. There are no plaques or signs outside. No one strolling by would think there was ever a time when one could have ducked inside its unlocked front door after midnight, walked up its creaky stairs, and sat down to watch and listen to all-night jam sessions by the world’s leading jazz artists at the peak of their powers. Or that Norman Mailer, Salvador Dalí, Anaïs Nin, or Willem de Kooning might be there, too, listening in, or chatting away in the next room.

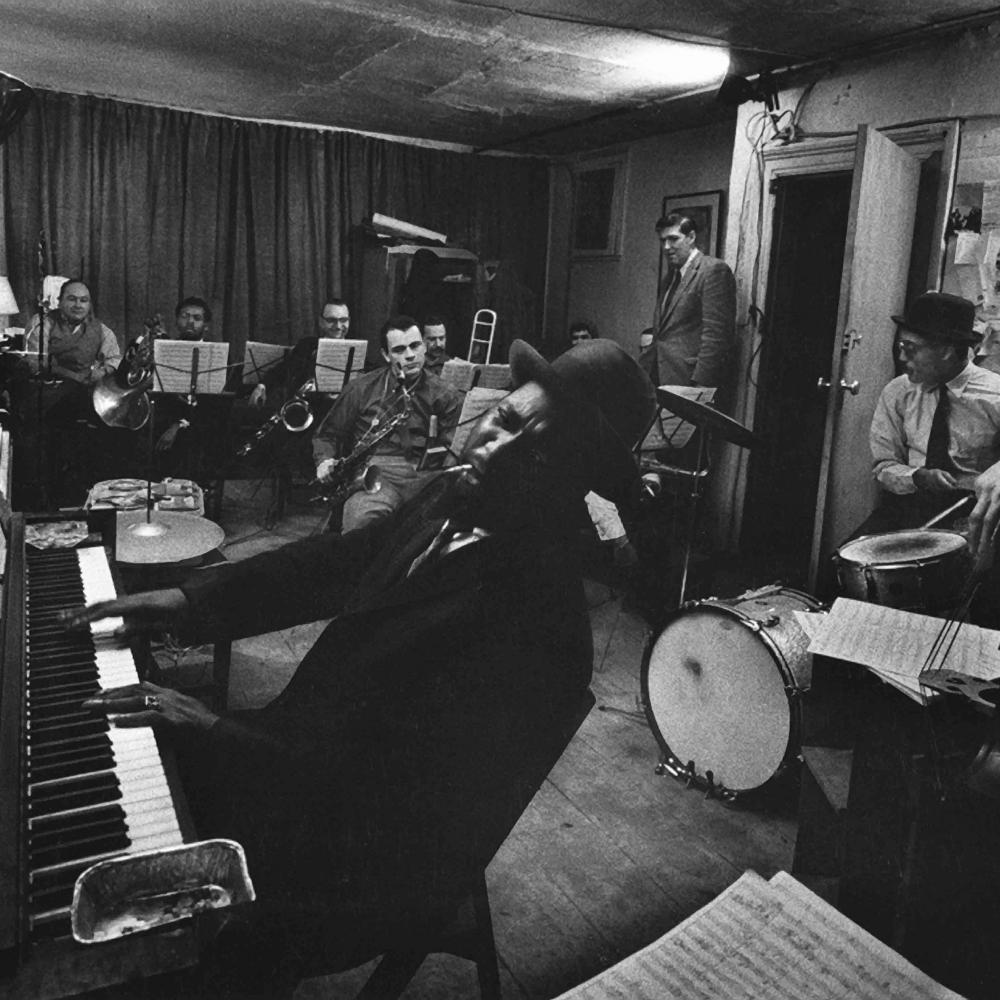

Hundreds of musicians played there, drawn to a space where they could stretch out, experiment, and expand the horizons of their own musical visions without the confines or expectations of audiences, club owners, or neighbors. No one got paid. No one paid to get inside. They were there to pursue the music, to see where it could take them, for the love of it and nothing more, and, deliberately or not, to play their own parts in the creation of the modern jazz era.

Young rented the top three floors of the building in 1954 for $120. He kept the fifth floor for himself and rented the third and fourth floors to two musician friends: Hall Overton, a pianist, composer, and educator; and Dick Cary, a trumpeter, composer, and arranger. Young had a voracious appetite for jazz and knew practice space for musicians was scarce. He found a $50 piano, had it hauled up through a window, and invited his acquaintances over to play. It didn’t take long for “the loft” to become a late-night scene. Located almost in the dead center of Manhattan, it was easily accessible from other parts of the city, yet isolated enough to exude a sense of personal and artistic freedom within its doors. Musicians would play a four- or five-hour gig at a legitimate club, then head to the loft with their instruments, often playing until dawn.

There were a handful of similar places in New York at the time, but the presence of Overton and Cary as residents lent 821 Sixth Avenue a cachet other “jazz lofts” lacked, not least because the pianos were tuned. It drew the biggest names in jazz: Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Chet Baker, Art Blakey, Dizzy Gillespie, Lee Morgan, Yusef Lateef, and Thelonious Monk. Musicianship was number one. You didn’t have to be famous to sit in, but you had to be good. Many of Overton’s students would come in to observe, including Steve Reich and Doris Duke.

Overton sublet half of his space to the photographer Harold Feinstein, sharing the fourth floor with him until 1957, when the imminent birth of Feinstein’s first child made him seek surroundings more conducive for family life. Feinstein turned the space over to his colleague W. Eugene Smith, whose life was heading in the opposite direction. Smith had just abandoned his wife and children, fleeing a huge house in Croton-on-Hudson in the midst of a profound professional and personal crisis.

At the midpoint of the 1950s, W. Eugene Smith was one of the country’s most renowned photojournalists. Credited with introducing the photo essay to American magazines, he was respected by his peers and highly paid for his exceptional and groundbreaking work. Shortly after beginning his career at Newsweek in 1938, he revealed a perfectionist streak earning him the label “difficult.”

During World War II, Smith started taking photographs for Life magazine. His work was daring and intense. Unafraid to get close in for a compelling image, he ended up severely injured by an explosive. After a long recuperation, he embarked on a legendary postwar career, creating masterpieces in the new form of photo essays, including The Country Doctor (1948), Nurse Midwife (1951), and A Man of Mercy (1954), about Albert Schweitzer’s work in Gabon.

Smith’s place in the pantheon of influential photographers is assured, but he remains less well known compared with many of his contemporaries, including Diane Arbus and Henri Cartier-Bresson (both of whom would visit Smith while he lived at the loft). The traits that made Smith a legend among his peers unmade him with bosses, earning him the nickname “Crazy Gene.” He shot obsessively and demanded an unheard-of amount of control over how his images were developed and published. His willingness to battle his editors earned him artistic respect, but eventually cost him his livelihood.

He quit Life at the end of 1954 over issues of artistic control, and accepted an assignment from the Magnum agency to shoot one hundred pre-scripted images illustrating the city of Pittsburgh’s bicentennial. The assignment was supposed to last three weeks. Smith took photographs for two years, ultimately producing 22,000 images. He never delivered the project to Magnum, unable to realize his vision. Today Smith’s work from Pittsburgh is widely acknowledged to be among the best of his career, but the experience was a fiasco he couldn’t overcome.

Retreating from failure, he moved to the fourth floor at 821 Sixth Avenue in 1957, embarking on what would become his largest undertaking, and, until a decade ago, his most obscure: “the Jazz Loft Project.”

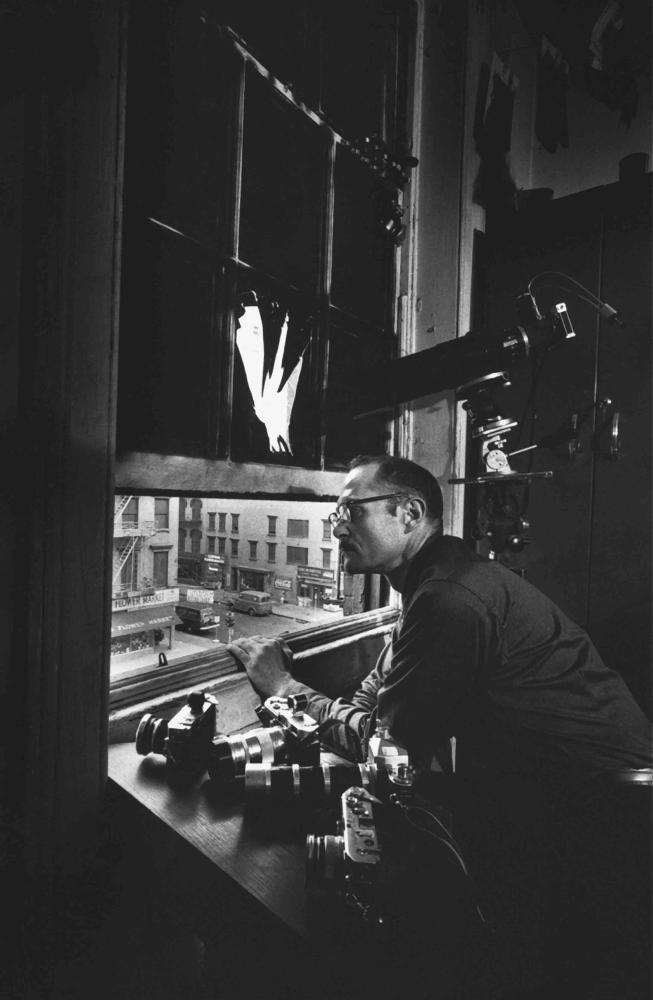

The scale of the “project” is almost impossible to exaggerate. Smith’s subject became life as he and others experienced it at 821 Sixth Avenue. He shot more than one thousand rolls of film, took more than forty thousand photographs, and made more than four thousand hours of audio recordings on 1,740 reels of tape. All of it originating from within the building, all of it captured between the front door and the ceiling of the fifth floor. More than twenty thousand images capture life as viewed by Smith from his window on the fourth floor. He famously wired the building with microphones, drilling through his neighbors’ walls and floorboards in an attempt to capture the results of their creative process and spontaneity. He sat in on jam sessions without an instrument, snapping away on his Leica, held near his hip like a gunslinger’s six-shooter. To observers who were present, none of Smith’s behavior came off as voyeuristic or revealed any hint of base intentions. He just wanted to be there, in the room, documenting what was happening. That was how he always worked, and working in the loft was no different.

The results can be interpreted as many things: artistic obsession; social, cultural, and musical anthropology; a work of staggering ambition in the realm of photojournalism, accompanied by what might be the world’s most unique soundtrack. All of the above, all rolled into one. His work wasn’t secret, but he tried to keep it discreet, playing the fly on the wall to the extent it was possible.

After Young, Overton, and Cary moved out of the building in 1964, the music stopped. Smith continued teaching in New York while living and working in the building until 1971, taking over the top three floors and filling them with boxes and boxes of prints and tapes until he was eventually evicted. He spent the next two years working on one last large-scale project, documenting the effects of mercury poisoning in Minamata, Japan. The project included one of his most iconic images, Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath, taken in 1971.

After Smith returned to the U.S. in fading health, Ansel Adams helped him obtain a teaching position at the University of Arizona in Tucson, where he spent his last years teaching and organizing his archives. When Smith died in 1978, he had already begun the descent toward obscurity, manifested by the state of his archives: 22 tons of material, stored in boxes at the University of Arizona’s Center for Creative Photography. That we know anything about any of it at this point is the result of respectful peers, diehard admirers of Smith’s work, and a couple of serendipitous accidents of history.

In 1994, Sam Stephenson, a young writer from North Carolina, became so captivated during his first visit to his wife’s hometown of Pittsburgh that he decided to write a book about the city. Still working on it in 1996, Stephenson was given, by his wife, a camera to help him capture images for the project. During a visit to a camera store in Raleigh, Stephenson learned of W. Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh project through a chance conversation with the shop’s owner, who just the night before had watched Photography Made Difficult, the 1989 American Masters documentary about Smith, which discusses the Pittsburgh project.

Intrigued, Stephenson read Jim Hughes’s authoritative biography, W. Eugene Smith: Shadow and Substance. Through his affiliation with Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies, Stephenson learned more about Smith’s Pittsburgh images and found his way to the archives in Tucson to view them in person. Stephenson’s original idea for a Pittsburgh book evolved into a book about Smith’s Pittsburgh project: Dream Street: W. Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh Project (2001, W. W. Norton and Lyndhurst Books of the Center for Documentary Studies).

While researching at the Smith archives in Tucson, Stephenson noticed rows of boxes stacked against a wall. Told the boxes contained tapes untouched since their arrival in the 1970s, Stephenson opened one of them and pulled out a box holding a reel of quarter-inch tape. There were names chicken-scratched on the cover. One stood out: Monk. Stephenson picked up another tape and turned it over. More names of jazz musicians he recognized. The Jazz Loft tapes had been discovered.

Stephenson acknowledges that the existence of the tapes wasn’t a secret, but the scope of organizing the 1,740 audio-tapes was beyond the ability and, frankly, the interest of anyone primarily concerned with Smith’s photography. As it happened, Stephenson was also very interested in jazz, and he revered the music of Thelonious Monk more than that of any other musician. The existence of the tapes kept pulling at his attention.

In 1998, Stephenson wrote an article about the Jazz Loft for DoubleTakemagazine, planting the seeds for what would become The Jazz Loft Project. He received a $65,000 grant from Reva and David Logan to preserve the tapes, and the project kicked into another gear when Stephenson applied for and received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The NEH grant provided him with time and financial resources to eventually raise $1.2 million. Over the next ten years, Stephenson and his partners transferred the contents of every tape (more than 4,000 hours of material) to digital files stored on over 5,000 compact discs. The tapes, and the 40,000 photographs Smith took at 821, most never seen before, became the subject of Stephenson’s second book, The Jazz Loft Project, published by Alfred A. Knopf in 2009.

In 2005, Sara Fishko entered the story. Fishko’s path to the project also seems serendipitous. A producer, host, and culture journalist for WNYC in New York City, Fishko was also an experienced documentary film editor. She possesses an extensive knowledge of music and a deep interest in jazz.

A friend of Fishko’s attended a talk given by Stephenson in New York, and told her a fascinating anecdote of a tape featuring Thelonious Monk dancing out a French horn solo on the floor for French horn player Bob Northern in preparation for Monk’s legendary 1959 Town Hall concert. Fishko called Stephenson almost as soon as she got off the phone with her friend, and the two hit it off immediately. She suggested they create a radio series focused primarily on the music, a project she knew would take years to complete, based on the volume of material Stephenson had unearthed, but one she knew would find a receptive, enthusiastic audience.

In 2009, “The Jazz Loft Project” radio series accompanied the publication of Stephenson’s book of the same name. The series featured ten episodes, focused primarily on the music and musicians. Only the second episode focuses on Smith. The book and radio series were well received by jazz enthusiasts nationwide.

Given the excitement generated by the book and the radio series, it wasn’t surprising someone eventually suggested a Jazz Loft Project film. At least a couple of well-known filmmakers expressed an interest, but the more serious the subject became, the more Fishko realized the collaboration between her, Stephenson, the Smith Estate, and WNYC was evidence they could, and should, make the film themselves. Stephenson agreed, so Fishko pitched the idea of making the film in-house at WNYC and the station agreed. Fishko would write, produce, and direct. Again, an NEH grant proved instrumental.

Fishko knew well that telling a story on film was very different from presenting it on the radio and immediately set about interviewing musicians. At the same time, she knew the film required a narrative arc to work, and that’s how Smith emerged as the center of the story, at least in this iteration. The film became The Jazz Loft According to W. Eugene Smith, capturing the essence and scope of what were now three distinct Jazz Loft projects, each presenting the material from a different perspective. Possibly, a fourth project awaits a meticulous mind with the time (and funding, no doubt) to create an online, nonprofit archive containing the entirety of W. Eugene Smith’s work at the loft, serving musical and cultural historians for decades to come.

Fishko’s film is the most immediate way to step into the world of the Jazz Loft Project, perhaps because it bears the closest resemblance to Smith’s own primary influences, which were music and theater. Smith revered Tennessee Williams, and he wanted his Pittsburgh project to have the profundity of late Beethoven. We’ll never fully understand how much and in what ways the jazz at 821 influenced his work or his personal life, or anything really, because, perhaps unsurprisingly, Smith never interviewed anyone at the loft, nor was he interviewed during that time.

He recorded dozens of his phone calls and conversations, but those taped moments, like those captured on film, seem intended to document life, no further explanation needed. That ethos served Smith well as a photojournalist, but it doesn’t help us understand what motivated his work.

Perhaps we shouldn’t try.

Stephenson has observed a pattern within Smith’s work. Starting with his World War II photographs, Stephenson says, Smith captured the human experience “very sympathetically, very compassionately.” Elsewhere his photography “indicts the larger culture” in which “the individual is sort of doomed, up against this bigger, often mechanical human enterprise.”

A similar contrast is seen in the Jazz Loft photos. Roughly half capture the spontaneity of artists at work and play, collaborating in the process of creation, inside the loft, a space uninterested in and unaccountable to the world outside.

The other half are taken from Smith’s window looking out onto Sixth Avenue, documenting commerce, the hustle and bustle of city life, in which everything, even the most personal gestures, can be seen as performing in the theater of survival.

Between the two halves is still something else that brings to mind what the photographer David Vestal said to Stephenson: “What Smith saw with his eyes was not catchable by a camera.”