“Although Jane Addams has had her day, she has yet to receive her due.” –Jean Bethke Elshtain

In 1889, Jane Addams, an idealistic college graduate, rented a run-down mansion on a derelict strip of Halsted Street in Chicago’s Nineteenth Ward. The neighborhood was home to thousands of recently arrived immigrants—Italians, Greeks, Russian Jews, Bohemians, and Irish. Addams, like many young people, was searching for purpose and meaning. Her plan was to use the mansion to improve the lives of the urban poor. Named Hull-House after its original owner, Charles Hull, it would become known as America’s first settlement house.

The settlement started with a kindergarten, then added a day-care center, then an art studio. The early residents, who lived in the house to help the community, held reading groups and sewing classes. They also delivered babies, nursed the sick, prepared the dead for burial, and, from time to time, sheltered young women from abuse.

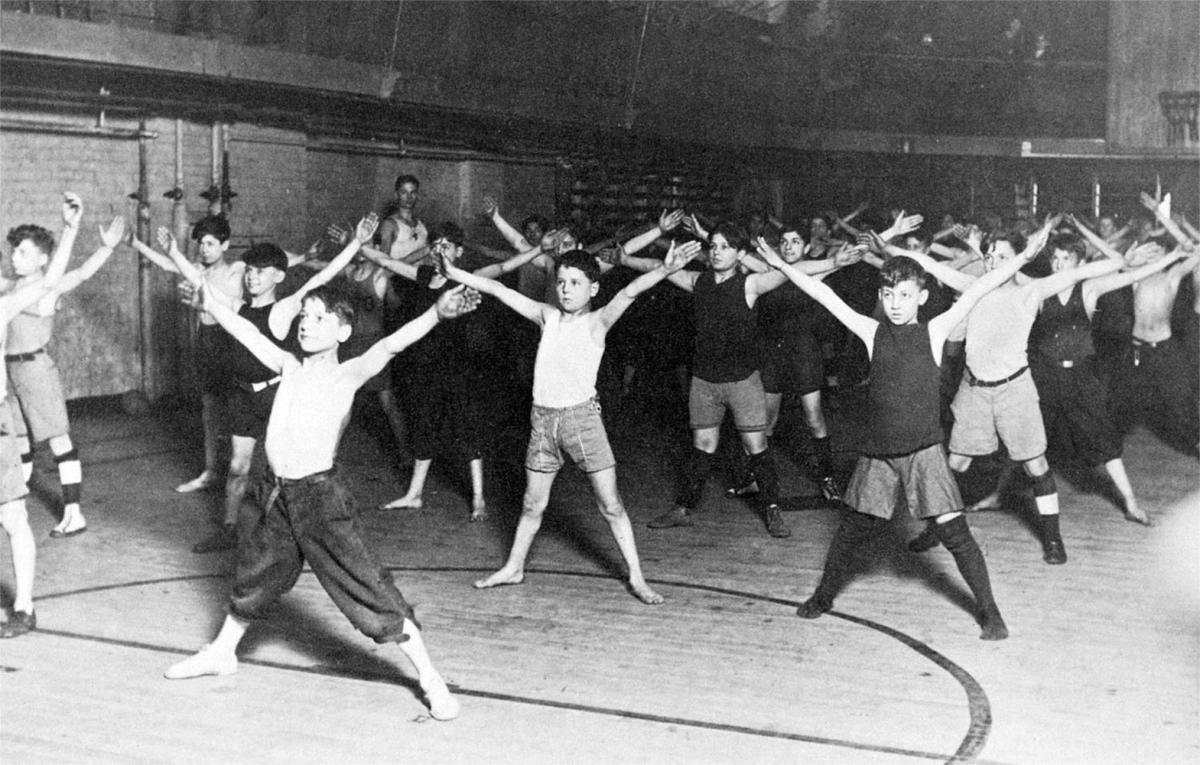

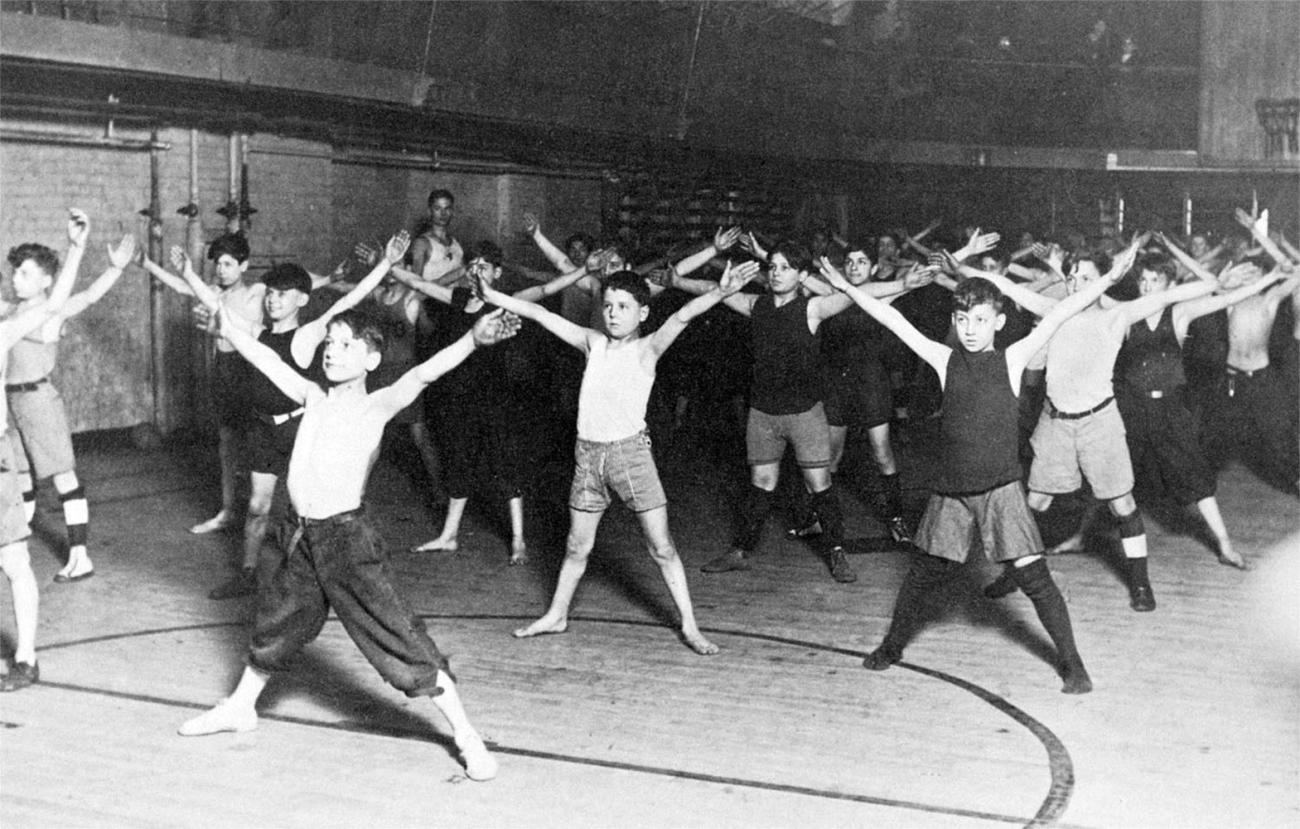

Over the next few years, Hull-House expanded to 13 buildings and became the home of many social workers who took on new tasks: English instruction, adult education, boys and girls clubs. Addams became its leader, administrator, fund-raiser, and defender. She reached out to politicians, business leaders, and philanthropists in Chicago and traveled to settlement houses springing up all over the United States.

Giving speeches and writing 11 books and hundreds of essays, editorials, and columns, Addams grew famous. Hull-House became a symbol of progressivism, the reform movement that flourished between 1890 and 1920 as it tried to better a country battered by industrialization, the explosive growth of cities, and the sudden arrival of millions of immigrants, mostly poor.

Today, interest in Jane Addams is keen, and her reputation is in ascent. Scholars have published three volumes of The Selected Papers of Jane Addams, with more volumes to follow. There are biographies for scholars, for the general reader, for young adults, and for children. At National History Day, a popular competition for middle and high school students supported by NEH, Jane Addams is a favorite subject. She was not, however, always so beloved. In her own time, the celebrated advocate of the poor was famous, then scorned, and, finally, reconsidered and elevated to the pantheon of American heroes.

Laura Jane Addams was born in Cedarville, Illinois, in 1860 on the eve of the Civil War. Tucked into the northwest corner of Illinois, Cedarville, in Jane’s memory, was a place of rural beauty. Jane’s father, John H. Addams, owned a flour mill and a sawmill. President of a bank and director of two railroad companies, he was elected Illinois state senator in 1854 and served eight terms. He was an abolitionist, a Quaker, and a friend of Abraham Lincoln, whose photographs hung in his parlor and study. Jane revered her father, characterizing him as “a man who held converse with great minds.” He introduced her to books, such as Thomas Carlyle’s On Heroes and Hero Worship, and insisted on the best education for his children.

Americans in the nineteenth century were familiar with death. After giving birth to eight children (only four reached adulthood), Sarah Addams, Jane’s mother, died in childbirth when Jane was two years old. Six years later, her father married Anna Haldeman, a cultivated widow devoted to the arts. It was a mostly happy childhood for Jane, yet one marred by memories of the Civil War, a preoccupation with the injustices of the world, and the death of her older sister, Martha, from typhoid. In a photograph taken in 1868, Jane stares out wide-eyed and intense, a young girl with a crooked back, the effect of spinal tuberculosis. She described herself as “homely.”

Privileged women were just beginning to attend college in the 1870s. Jane hoped to attend Smith, but her father wanted her close to home, so she attended Rockford Female Seminary (where he was a trustee), a school noted for graduating missionaries. Jane excelled at the seminary, developing a social conscience, becoming valedictorian, and gaining recognition as a leader. She learned to write and to speak in public, skills that would one day contribute to her celebrity.

Not always serious and priggish, Jane could also be irreverent, even naughty. In her autobiography, she confesses that she and some classmates at the seminary read Confessions of an English Opium-Eater by Thomas De Quincey and even went so far as to imitate the author. Hoping to understand De Quincey’s dreams more deeply, Jane and her friends drugged themselves with opium during a long holiday. Discovered disoriented by a young teacher, the girls had their books and white powders confiscated, were administered emetics, and sequestered in their rooms.

What to do after graduation? Jane Addams never mentioned pursuing marriage or having children. Instead, she dreamed of becoming a doctor and helping the poor, but the eight years after graduation (1881–1889) were difficult. Her father, at age fifty-nine, died suddenly of appendicitis. Jane’s mentally ill brother needed attention. For her own curvature of the spine, she traveled to Iowa for an operation, spent two months immobilized, and was treated for neurasthenia by the country’s preeminent nerve doctor, S. Weir Mitchell. In her autobiography, Addams recalled, “The long illness left me in a state of nervous exhaustion with which I struggled for years, traces of it remaining long after Hull-House was opened in 1889.”

Addams gave up her dream of becoming a doctor, took her father’s generous inheritance, and, with friends and her stepmother, traveled twice to Europe in pursuit of self-cultivation and purpose. But art museums and opera did not give her peace or satisfy her slumbering social conscience.

Addams read Leo Tolstoy’s My Religion, in which the great novelist confessed his personal failure and his commitment to Christian service and nonviolence, describing how he had found purpose and satisfaction living with peasants. She traveled by horse-drawn omnibus to London’s impoverished East End and visited Toynbee Hall, an English settlement house, where Oxford and Cambridge graduates lived and worked among the destitute. After attending a bullfight in Spain in 1888 with a close friend, Ellen Gates Starr, Addams confided her dream that together they would plant a replica of Toynbee Hall amid the tenements of Chicago.

Back in Chicago, the two women brightened up the dingy mansion in the Nineteenth Ward with old furniture and replicas of famous paintings. They reached out to the impoverished neighborhood with goodwill, day care, discussion groups, bath houses, and the first playground in Chicago. To have significant impact, however, Addams realized that Hull-House needed to be more than a cultural and community center. Garbage spilled over from wooden boxes and needed collection. The muddy streets needed paving. Goodwill was not enough.

In 1895, Addams had herself appointed garbage inspector, her first paid job. She served on a commission to investigate conditions in the county’s poor house. She helped found the Juvenile Protective Association to keep liquor, tobacco, and indecent postcards out of the hands of minors. Discovering that change required political action, she fought against John Powers—a corrupt alderman uninterested in good government—in three bitterly contested elections while being assailed with hostile and often obscene letters.

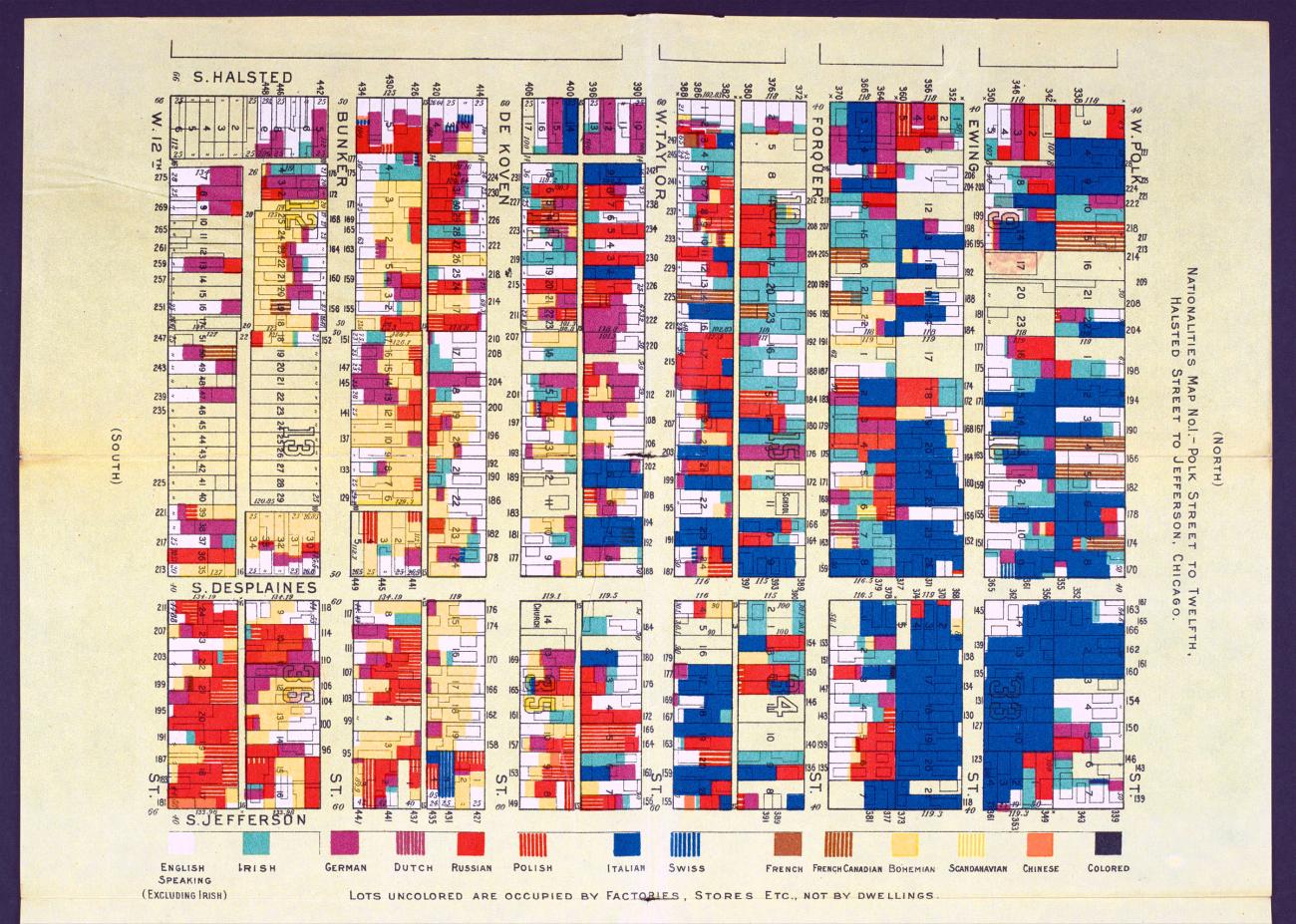

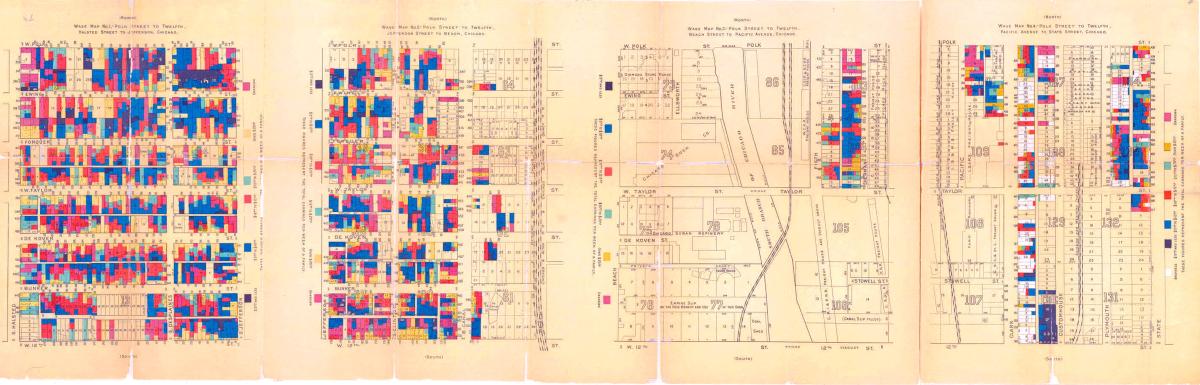

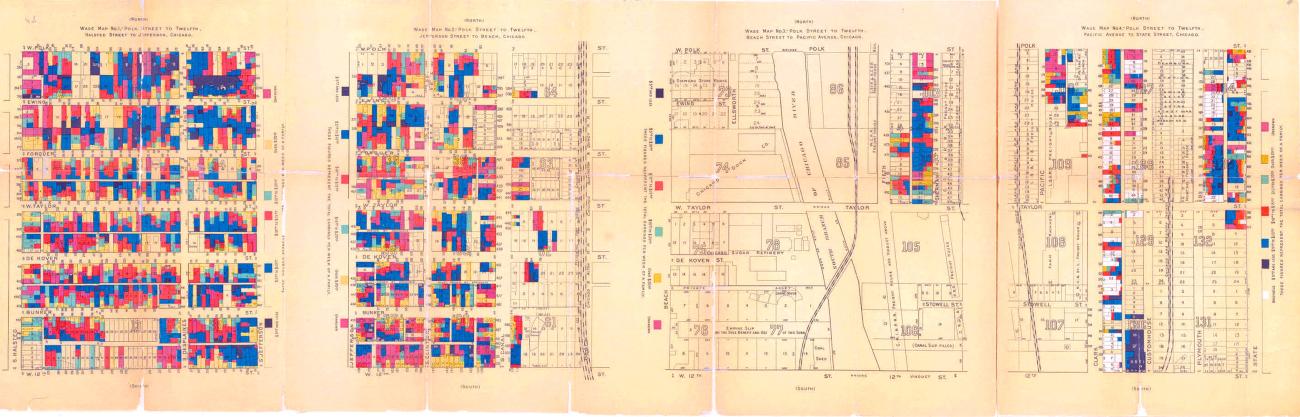

Hull-House residents in time mapped the Nineteenth Ward and, in 1895, had the results published in Hull-House Maps and Papers, a systematic inventory of an American urban slum. The residents went on to collect figures on wage-earning children and to study saloons, truancy, tuberculosis, cocaine, and midwifery. Addams understood that investigation must precede action. She wrote that one “must be a patient collector of facts.”

Addams and Starr did not work alone. Julia Lathrop, whom Addams had met at the Rockford Female Seminary, organized a discussion group, the Plato Club. Recognizing a more urgent need—children in jail—Lathrop helped found the country’s first juvenile court.

Florence Kelley, an avowed socialist, and her three children fled from her abusive husband to Hull-House. Upset with the long hours of working women, Kelley took legislators on tours of sweatshops. In 1893, Governor Peter Altgeld appointed her Chief Factory Inspector for the state of Illinois, her work contributing to an eight-hour workday for women.

Alice Hamilton fulfilled Jane Addams’s dream by graduating, in 1893, from the University of Michigan’s medical school. Living on and off at Hull-House in the 1890s, Hamilton attempted to identify causes of typhoid and tuberculosis in the surrounding community, became an expert on lead poisoning, and went on to have an exceptional career in public health.

In a pamphlet titled “The Excellent Becomes the Permanent,” Addams eulogized those who made Hull-House work. One of Addams’s most appealing qualities was giving credit.

Of course, help also came from Washington. Addams was friendly with and consulted by progressive presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, who supported regulating corporations, protecting consumers, improving the environment, and legitimizing unions.

Addams’s closest companion was Mary Rozet Smith, a tall and attractive debutante, trustee of Hull-House, and one of its leading benefactors. The two lived and traveled together and owned a house in Maine. Addams referred to their relationship, which lasted 37 years, as a “marriage.” She destroyed many of Smith’s letters. In our less reticent age, skeptical of affectionate female friendships, there is speculation among historians about their relationship.

Addams and her colleagues at Hull-House were not the only critics of poverty during the Gilded Age and the Progressive era. Henry George’s 1879 denunciation of class division, Progress and Poverty, sold millions of copies worldwide. Edward Bellamy’s 1888 novel, Looking Backward, imagined Boston in the year 2000 where a benevolent government provided universal prosperity and equality. Thorstein Veblen eviscerated the idle rich and coined the phrase “conspicuous consumption” in The Theory of the Leisure Class.

Nor was Hull-House the only center of activism. Influenced by Henry George, Tom Johnson gave up a lucrative business career and, as mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, for four terms (1901–1909), made the city more efficient and humane with a multitude of reforms. Samuel Milton Jones did the same for Toledo, becoming such an idealistic municipal reformer that he became known as “Golden Rule Jones.”

Balanced historians remind us that the squalor of the Nineteenth Ward did not represent all of America. Incomes were rising, trade was increasing, and productivity was surpassing that of Europe. Central heating, clean water, and artificial light became more widespread. Life spans increased.

In a flattering photograph taken in middle age, Addams appears ever serious, confident, and melancholy. What were her beliefs? An intellectual steeped in uplifting Victorian literature, she easily quoted Robert Browning, Thomas Carlyle, and George Eliot, one of her favorite novelists, who wrote, “The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric works.” When trying to explain the Pullman Strike of 1894, Addams turned to Shakespeare in her essay “A Modern Lear.” In 2020, Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro stated that he had learned more about the labor-management struggle in Gilded Age America from this essay than he “had ever been taught in school.”

Though devoted to European culture, Addams was at heart an American democrat who rejected the English class system. Mesmerized by Tolstoy, she visited him in Russia in 1896 and became a lifelong pacifist. Tolstoy, who had hundreds of visitors over the years, seemed unaware of her Chicago fame and chided her fashionable leg o’ mutton sleeves, which he found decadent. He also suggested she sell her real estate and work in the Hull-House bakery.

Addams valued immigrants, repudiating restrictions and literacy tests. She believed simultaneously in Americanization and retention of ethnic identity. She supported trade unions and strikes but rejected anarchists and the militant Industrial Workers of the World. Skeptical of socialism, she repeatedly criticized the excesses of capitalism. Always, Jane Addams was an unwavering suffragist, connecting the vote to improving the lives of the families in the Nineteenth Ward. Witnessing the damage alcohol did to families in her ward, she remained a convinced prohibitionist.

Like most middle-class progressives, Addams believed more in cooperation, less in competition and individualism; more in government and regulation, less in laissez-faire. She insisted that environmental factors (housing, unemployment, disease) caused poverty, not laziness or irresponsibility. She hated confrontation and tried to see both sides of issues. Although steeped in the Bible, she did not believe in the divinity of Jesus, substituting theology with what reformers at the time called the “Social Gospel,” an emphasis on the ethical teaching of Jesus. Addams rejected conventional charity or philanthropy, insisting that it was patronizing and instead endorsed what she called “a cooperative ideal of mutual assistance.”

Addams conveyed her beliefs in hundreds of speeches and dozens of articles in best-selling magazines such as The Ladies’ Home Journal and McClure’s. Her speeches and articles turned into books. She wrote about poverty, peace, and prostitution. Her favorite of her own books was The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets, a cautionary tale she wrote in 1909 about the dangers of the anonymous city to the mental health of children and the growing problems of gangs and juvenile delinquency.

No longer just a keeper of Hull-House, the improver of the Nineteenth Ward, Jane Addams spoke out on the leading issues of the day—condemning the war in the Philippines, lynchings in the South, and race riots in Atlanta and Springfield. In addition to her role as an activist, she became a sociologist and a scholar. Her books were reviewed by prominent thinkers. William James wrote to her: “Yours is a deeply original mind.”

Her first book, Democracy and Social Ethics, which James admired, emphasizes such phrases as social equality, moral idealism, civic virtue, association, industrial amelioration—all words and ideas she repeated in her subsequent books. These concepts reflect Addams’s worldview and the progressive credo.

What was Jane Addams like? A hero worshipper, she always remained in awe of her father and his hero, Abraham Lincoln. According to her stepmother, Jane was like her father, fiercely ambitious. Maternal, she kept track of and took care of her extended family. A feminist, she believed in equal rights for women. Simultaneously, she thought of women as fundamentally different from men, even superior—compassionate and intuitive—the keepers of home, the protectors of children, the preservers of peace.

Insatiably curious, Addams read constantly and listened intently. She applied what she read and heard to the problems of her ward. To defend civic virtue, for example, she invoked John Stuart Mill. To explain social morality, she turned to Tolstoy’s Master and Man. Biographer Anne Firor Scott believes she had “the combination of a mystical-intuitive turn of mind with a down-to-earth interest in how things worked and a fine capacity for observation.”

Addams hated to be alone, even when writing. “Friendship is . . . after all the main thing in life,” she wrote. She liked good conversation and smart people and debate. She believed in self-discovery, self-discipline, and self-improvement. Her nephew and first biographer, James Weber Linn, pointed to her keen sense of humor. Not a prude, she believed in sex education, but criticized the hedonism of the 1920s and its fascination with Sigmund Freud. A workaholic, she wrote and traveled constantly. Cosmopolitan, she made 12 journeys abroad, despite her intermittent ill health. While traveling, she worked at her embroidery and crochet.

A charismatic speaker, Addams was constantly in demand. “From the first word to the last,” her niece remembered, “she held the complete attention of her audience.” A woman of conviction, Addams was also a politician and compromiser. Generous, she had spent her inheritance on Hull-House and its many activities. By the mid 1890s and for the rest of her life, she lived off income from her writing and public speaking. Self-possessed, she moved easily among the wealthy and famous, perhaps a result of being born into the upper class of Cedarville. Simultaneously she reached out to the immigrants of the Nineteenth Ward and practiced the brotherhood she preached.

Money was always a preoccupation. Hull-House never had enough. She had to solicit donors. Her extended family needed help. She haggled with publishers over advances. Aware of her celebrity, she collected a scrapbook of hundreds of articles extolling her influence. Allen Davis, a sympathetic but critical biographer, writes that Addams was “ambitious,” and “eager for publicity”—an admirable human being, but not just the self-sacrificing saint the public craved.

Of course, Addams had her critics. Aldermen didn’t like being removed from office. Patriarchs thought women should stay home. Conservatives opposed change. Socialists wanted more. Many Chicago businessmen considered her a dangerous radical. Addams believed that the remedy for sprawling cities and dehumanizing factories was cooperation among classes and ethnic groups. To achieve this “socialized democracy,” she believed America required an active, benevolent government and wise regulation. Conservatives (then as now) believed that entrepreneurs and capitalism produce abundance, that competition motivates workers, that social classes were inevitable, and that trade unions and government interfered with freedom.

Fame had come early for Addams. Visitors to the 1893 Columbian Exposition included Hull-House in their itinerary. In 1902, she had published her first major book, Democracy and Social Ethics. Prominent public intellectuals of the early twentieth century drew audiences to the Hull-House Theatre: educator John Dewey, sociologist W.E.B. DuBois, suffragist Susan B. Anthony, attorney Clarence Darrow, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, journalist Ida B. Wells, and Theodore Roosevelt. Biographer Jean Bethke Elshtain notes in her introduction to The Jane Addams Reader: “Nearly every piece of major reform in the years 1895–1930 comes with Jane Addams’s name attached in one way or another.”

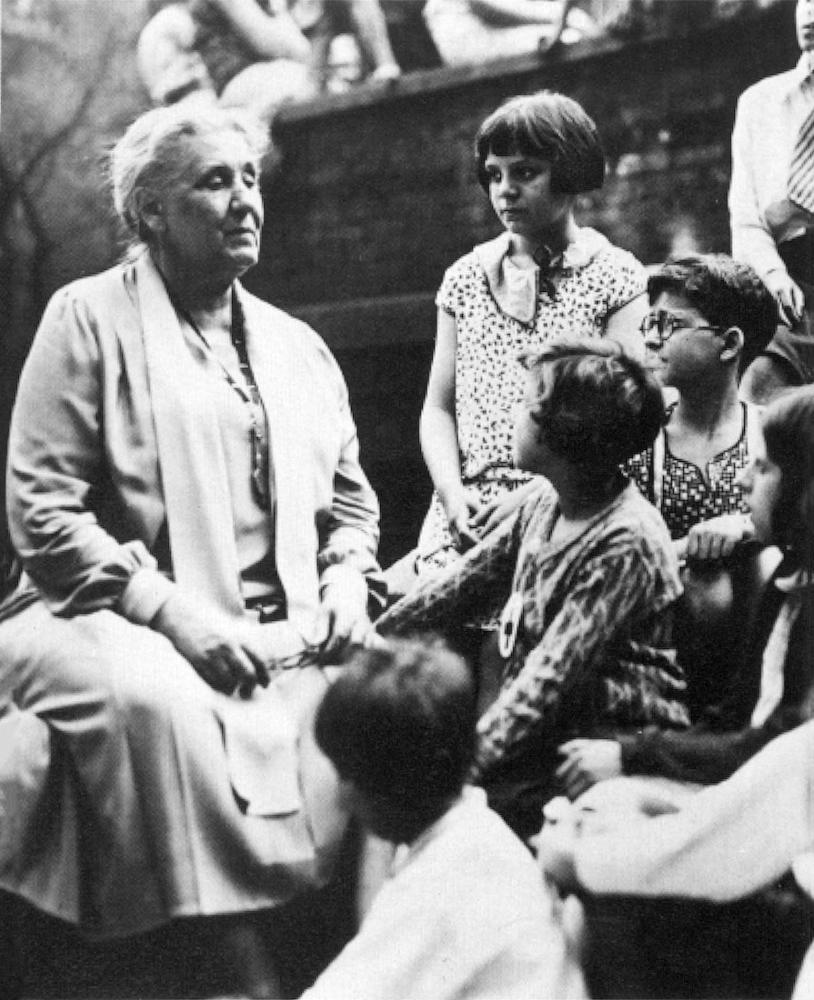

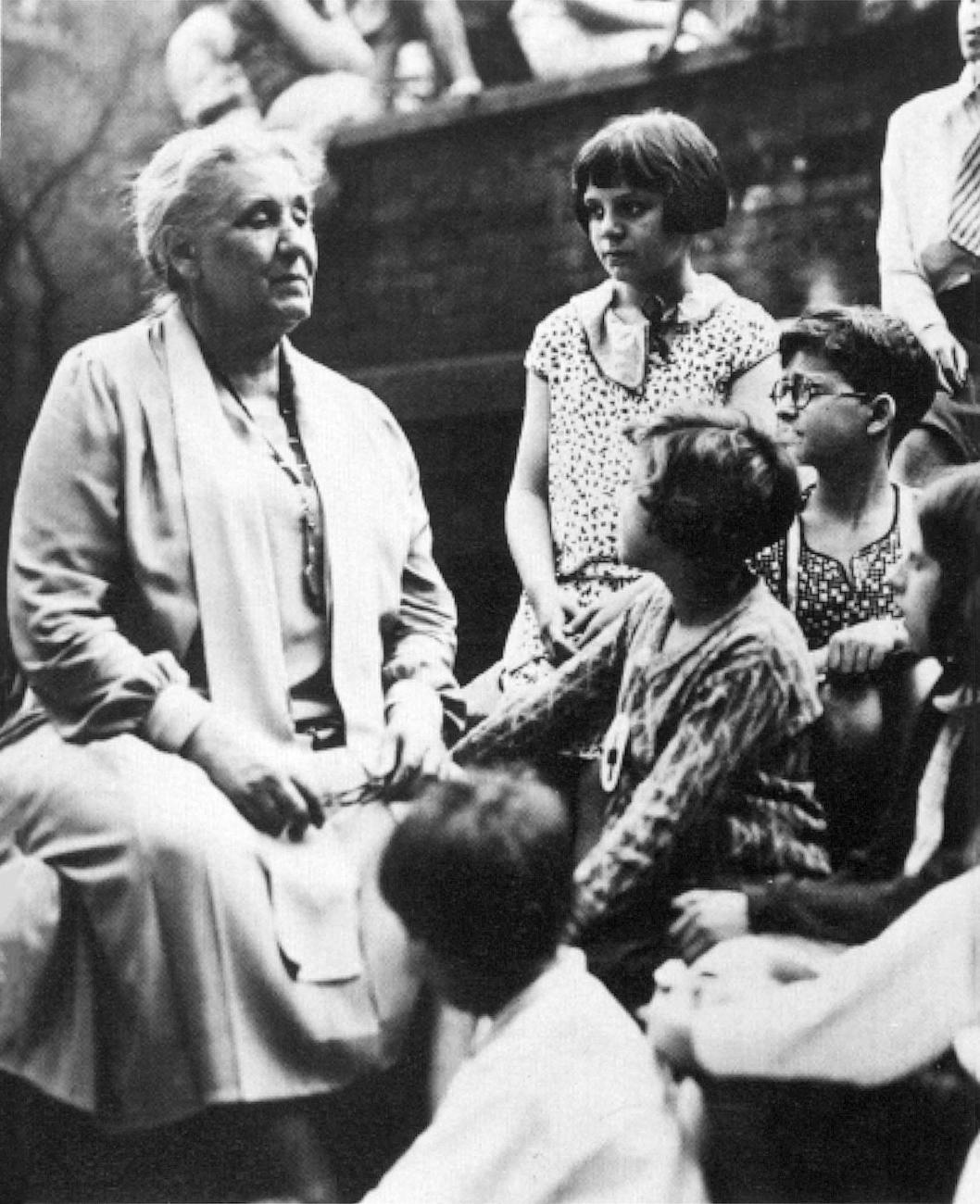

At age fifty, Addams published her autobiography, Twenty Years at Hull-House. Her account was personal, modest, and candid, blending her accomplishments and progressive philosophy with poignant portraits of immigrants in the Nineteenth Ward. It quickly went through six printings and was translated in German, French, and Japanese. An optimistic book, it is regularly excerpted in contemporary books for young adults and children as well as in literature anthologies and history texts. By 1910, Jane Addams had become a household name, a beloved national figure, the recipient of honorary degrees. She would also appear in movies and later on radio.

This all changed in 1914 with the start of World War I. Her dream of increasing internationalism and declining militarism was shattered. Europe suddenly descended into chaos. The United States slowly rearmed and crept toward war. Addams opposed the war, remained a pacifist, and became a pariah. No sentimental pacifist, she had denounced war in her 1907 book Newer Ideals of Peace, insisting that there is no honor or glory in fighting, that naïve young men and innocent civilians are victims, and that arbitration can be effective in an increasingly interdependent world. Humans were not innately pugnacious.

Elected head of the newly formed Women’s Peace Party in 1915, Addams traveled to The Hague in the spring of 1915 to preside over an international conference made up of delegates from both warring and neutral nations. With some of the delegates, she then traveled to the warring nations, meeting foreign ministers, visiting wounded soldiers and grieving mothers, and absorbing the carnage ruining Europe. Returning to the U.S. in July 1915, she spoke to a peace rally at Carnegie Hall before a largely friendly audience of three thousand people. She ended her speech describing the way liquor was doled out to soldiers before bayonet charges.

The ensuing reaction to her insinuation that combatants were not inherently brave and self-sacrificing was brutal. Newspapers attacked Addams, one calling her a traitor and a fool. Theodore Roosevelt derided Addams, calling her a “Bull Mouse,” and the women of The Hague for seeking “peace without justice.” The attacks on her accelerated when the United States entered the war in April of 1917, and Addams, unlike many progressives, refused to join the pro-war patriotism that swept the country. According to biographer Victoria Bissell Brown, “the war convinced Addams that women simply cared more about life than men did.”

Sick for much of the war, isolated and shunned, Addams escaped self-pity by joining with Herbert Hoover in the humanitarian issue of food, urging Americans to conserve food and to send the surplus to starving Europeans. She reminded herself that part of Wilson’s plan for “a peace without victory” resulted from the recommendations made at the Hague Conference she had led before the war.

The armistice of November 11 ended the war. Addams returned to Europe, this time to Zurich to preside over the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, attended by some 150 delegates from 16 countries. Before the conference began, she took a five-day journey, walking through towns devastated by war, passing houses shattered by artillery, and seeing emaciated children everywhere. With Alice Hamilton, she trudged through rain and mud to the cemetery at the Argonne searching for the grave of her favorite nephew, Captain John Linn, who had been killed by shellfire about a month before the armistice.

The Zurich delegates protested the punitive Versailles Treaty, which assigned blame for the war to Germany and imposed costly war reparations that ruined its economy, although they approved of the League of Nations. Addams returned to America and Hull-House. In the words of one of her biographers, she returned to “failed peace plans, corrupt politicians, FBI surveillance, blacklists and heckling audiences.”

The 1920s were not easy for Addams. Progressivism was in retreat. Americans celebrated business, not reform, corporations, not settlement houses. Race riots and the Red Scare at the start of the decade gave way to prosperity before the crash of 1929. Despite illness and a declining income, Addams remained resilient, tending to Hull-House, continuing to advocate for old-age pensions in the midst of the Great Depression, and presenting President Hoover with a petition for disarmament signed by some two hundred thousand women voters.

Addams wrote her last autobiography in 1930, The Second Twenty Years at Hull-House, which was less optimistic than her first and critical of the postwar generation. In the last chapter, she criticizes the racism of the 1920s, citing discrimination in housing and employment and noting pervasive arrogance and insolence. Praising the zeal of the nineteenth-century abolitionists, she condemns contemporary Americans for a failure “to remove fetters, to prevent cruelty.” She then bluntly warns, “We have allowed ourselves to become indifferent to the gravest situation in our American life.”

Never repenting her pacifism, Addams spent the last half of her life denouncing war in impassioned speeches and in subtle, convincing articles that gained in relevance as the Great War increasingly seemed futile. Whether her opposition to militarism would have remained steadfast with the challenge of Franco, Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin will never be known. To the public and most historians, however, she is more revered and remembered as a social reformer than as a critic of war.

While Addams was undergoing an operation for an infection, doctors found cancer. She died three days later on May 21, 1935. The funeral took place at Hull-House before thousands of grieving residents of the Nineteenth Ward. She was buried in Cedarville next to her parents. Walter Lippmann delivered an eloquent eulogy: “She had compassion without condescension. She had pity without retreat into vulgarity. She had infinite sympathy for common things without forgetfulness of those that are uncommon. That, I think, is why those who have known her say that she was not only good, but great.”

The reputations of heroes rise and fall. Addams went from the revered creator of Hull-House, an esteemed public intellectual, to the naïve pacifist and traitor to her country. In her last years, she became the respected humanitarian who foresaw the folly of World War I and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931.

No longer just a saint and social worker, scholars now praise Addams as an intellectual and theorist. Her 11 books, hundreds of articles and reviews, and thousands of letters offer academics abundant material for commentary and debate. Some see her as a pioneering sociologist, a contributor to John Dewey’s educational thought and to William James’s pragmatic theory. Others study her oratory, writing style, and changing religious beliefs.

In my recent interview with author Marilyn Fischer, who has edited four volumes of Jane Addams’s writings on peace and written a book that connects her to nineteenth-century evolutionary thought, Fischer praises Addams’s “extraordinary creativity” and “gracious, vigorous prose.” During a conversation with Rima Lunin Schultz, former assistant director of Hull-House, Schultz reminds me that Addams used art to promote social solidarity and championed the Hull-House music school, art studio, and labor museum.

Many scholars stress Addams’s relevance, reminding us that we are still debating poverty, patriarchy, racism, immigration, assimilation, and class divisions. Despite the feminist revolution, increasing equality in the workplace, politics, and education, women still face a conflict between work and what Addams called “the family claim.” In the #MeToo movement, women still contend with aggressive male sexuality that she critiqued in her 1912 book A New Conscience and an Ancient Evil. In an era of sexual openness, preoccupied with gender and identity, Addams’s personal life is scrutinized, her female friendships celebrated. Recently she was inducted into the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame.

Sociologist Erik Schneiderhan notes the striking parallels between Addams and Barack Obama, who has cited “Jane Addams toiling in a Chicago settlement home” as an inspiration. A young, idealistic Obama sought purpose as a community organizer on Chicago’s South Side as did Jane Addams in the Nineteenth Ward. Both went into politics and quickly became famous. Each wrote books and was a privileged intellectual with a social conscience. Each was a good listener and respected ordinary people.

In his most recent book, The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again, Robert D. Putnam with Shaylyn Romney Garrett looks back to the Progressive era and to Jane Addams for guidance on how to mitigate class division and poverty and become a less narcissistic nation. Addams, Putnam argues, stood for community and cooperation, rejecting the hyper-individualism of the nineteenth-century Gilded Age. Today, he claims, “America has become steadily less equal, more polarized, more fragmented, and more individualistic—a second Gilded Age.”

Addams believed that democracy was not only a political theory, but a way of life. One of the purposes of Hull-House was to make citizens. Elshtain praises Addams’s “celebration of citizenship and her lofty view of the call to civic life.”

As a scholar of heroism and a former teacher of secondary-school students, I am always looking for exemplary lives. Jane Addams’s father revered Lincoln. Jane absorbed Thomas Carlyle’s On Heroes and Hero Worship and revered Jo in Little Women. I think of Jane Addams as a hero—a woman of extraordinary achievement, courage, and greatness of soul. I see a role model for today’s youth caught up in a celebrity entertainment culture like the youthful immigrants of the early twentieth century who haunted saloons and movie houses described in Addams’s book The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets.

Heroes are contested and surrounded by legends and myths. Allen Davis, who wrote the first scholarly biography of Jane Addams in 1973, American Heroine: The Life and Legend of Jane Addams, wanted to create an objective and realistic portrait. Davis admired her, praising her as an outstanding person and significant reformer, but not as an original thinker.

Sociologist Christopher Lasch pushed back against Davis, calling Addams “a thinker of originality and daring.” Lasch is joined by other scholars, such as Louise K. Knight, who praises Addams’s synthesizing, strong, logical mind. Other critics claim Addams was overly optimistic, lacking a “tragic view” of life. Knight disagrees, citing Addams’s unsentimental realism and reminding us that she was very familiar with death and suffering.

In a recent interview with Stacy Pratt McDermott, assistant editor of the Jane Addams Papers, I asked her why Addams is not today accorded the praise and prestige of the philosophers John Dewey and William James. Her answer: “Sexism has excluded Addams from the canon of outstanding thinkers.”

Jane Addams lived from 1860 to 1935, from the Civil War to the Great Depression. Her work foreshadowed the New Deal and the Great Society. She was a social justice progressive urging Americans to become more equal, cooperative, peaceful, and kind. Instead of giving in to neurasthenia, she traveled from Cedarville to Chicago intent on improving the lives of the immigrant poor. Not content with creating an influential settlement house and spearheading innumerable reforms, she became a public intellectual, asking complacent and prosperous Americans of the early twentieth century to look beyond the glittering department stores and skyscrapers, the mesmerizing inventions of automobiles and airplanes, a bicycle craze and the Gibson Girls, and instead to look at the sweatshops, slums, and stockyards. She urged Americans to consider the factory workers who endured long hours with low wages—and to pay attention to the children who, instead of being at work, should have been in school.