with me

from myself to myself

outside any constellation

I hold in my hands only

the rare sobbing of a last delirious spasm

vibrate word

–Aimé Césaire, “Word,” Black Orpheus, Volume 2, 1958

In September 1956, the first International Congress of Negro Writers and Artists convened in Paris at the Sorbonne. Held under the auspices of the francophone literary journal Présence Africaine, the conference was one of the catalytic events leading to the establishment of both the anglophone journal Black Orpheus a year later and the Mbari Artists and Writers Club in Ibadan, Nigeria, in 1961. The Nigerian club and publication operated for a decade, but its writers and artists wove an influential network of ideas across postcolonial Africa and the world that remains today.

Jacob Lawrence visited Nigeria, a newly independent nation, and the club twice, in 1962 and again in 1964. He was one of the first Black American artists to receive major support—from the U.S. government and private foundations—in the segregated art world of the 1940s. His most widely known works include The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, a group of 41 paintings about the establishment of the first Black republic, Haiti, and his 60-panel Migration series, charting the stories of Black Americans leaving the South for a new life above the Mason-Dixon Line.

Lawrence’s lesser-known Nigeria works frame “Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club,” the exhibition currently visiting the New Orleans Museum of Art from the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia. Co-curated by Ndubuisi Ezeluomba and Kimberli Gant, the show acts as an entry point into the dynamic aesthetic, spiritual, and political world of 1960s continental Africa and its diaspora. The exhibition reveals the overlapping, sometimes conflicting, and parallel concerns of African artists articulating a new postcolonial cultural identity and Black American artists’ participation in and artistic response to the civil rights movement. Each of the exhibition’s five thematic sections relate to the journals themselves. This presentation of the journals, with the artwork they often featured, layers the relationship of the writers and artists, who recognized the linkage in their practices. The journals also function as an affirmation of the relationship between the word and the visual and its importance to establishing a new African canon.

Lawrence traveled to Nigeria, the first time, to close an exhibition of 25 panels from his Migration series. It was a short stay of ten days, but Lawrence would return in 1964 with his wife, Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, for a longer eight-month sabbatical. His second trip would prove more fraught but also fruitful. The FBI had opened a file on Lawrence in 1953, identifying him as a security risk with links to the Communist party. This surveillance left him unable to receive State Department funding for his trip, and Nigerian and American authorities made the first month of their stay difficult. Quoted in Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence recalled that the local governments were wary of the Lawrences, believing they had a relationship with the authorities, while those same agencies were making it difficult for them to secure housing. The pressure eventually relented, and Lawrence went on, with Gwendolyn, to give lectures and conduct workshops in Ibadan with the Mbari Club and also with Mbari Mbayo, the Osogbo-based group 60 miles away. The historical record is sparse, and Lawrence left little commentary about his time in Africa, but there is no doubt the connection was significant for him. He returned to Nigeria, selling his Brooklyn apartment to do so. The works he created there also demonstrate the impact Nigeria and its people had on his practice.

Quoted in Kimberli Gant’s essay “Jacob Lawrence: A Journey to Nigeria,” Lawrence comments on his own way of seeing: “I look around this room . . . and I see pattern: I don’t see you. I see you as a form as it relates to your environment. I see that there is a plane, you see, I’m very conscious of these planes, patterns.” Using tempera, gouache, crayon, and pen and ink, Lawrence used his dynamic technique to create epics of everyday Black life on both sides of the Atlantic. Influenced by Howard University professor Alain Locke, one of the preeminent figures of the New Negro Movement (later called the Harlem Renaissance), Lawrence was acutely aware of African art’s influence on European modernism. In his book Negro Art: Past and Present, Locke asserted that “Negro or African Art has been the most powerful force in modernism and art.” Patricia Hills writes in her catalog essay, “Cultural Legacies and the Transformation of the Cubist Collage Aesthetic by Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, and Other African American Artists,” that European artists working with cubism, such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, had studied African artifacts, masking, and sculpture at the French Musée de l’Homme and through their own private ownership. African art’s inclination toward abstraction was not, as Locke wrote, “a crude attempt at realism, an unsuccessful attempt to imitate nature, but a skillful reworking of these forms in simplified abstractions and deliberately emphasized symbolisms.” Black American artist Romare Bearden, Lawrence’s contemporary, concurred, asserting that the African impetus to distort the figure in order to create a more expressive form was one of the cardinal principles of the modern artist. Lawrence, observing the visual languages of African art and European modernism, seized upon the syncretic practices of Black American material culture, oral storytelling, and home decor to create a distinct presentation of his cubist aesthetic that he called “dynamic cubism.”

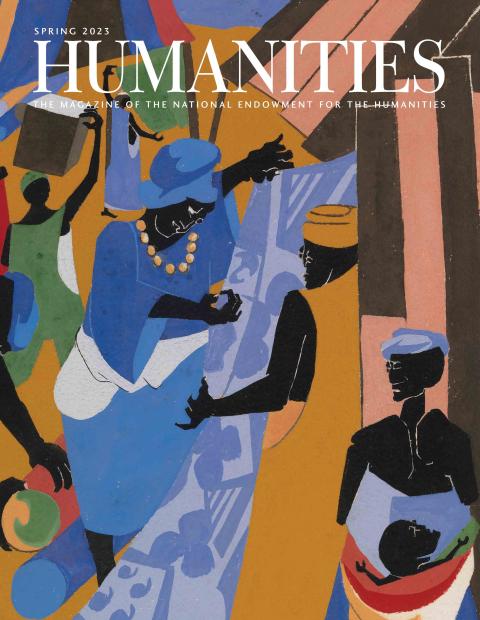

Lawrence’s Nigeria series focuses mainly on marketplace scenes, the interactions of Nigerian women, and spirituality. One work, Street to Mbari, with its intentional blocking of action creates a rich tapestry. Lawrence creates a visually dense world of figure and pattern while simultaneously individuating figures in the group cacophony. Looking closely at the people depicted in a work like Street to Mbari, one can see the jewelry, articles of clothing, and unique cheek scarification rendering personal identity. Lawrence harnessed the use of collage cubism to present the colliding physical and metaphysical qualities of human experience. Lawrence’s approach to cubism’s repetitive layering of flattened shapes, mimicking the look of paper collage in his Nigeria series, is a culmination of his syncretic combination of modernist technique, African art, and Black American cultural aesthetics. Lawrence often remarked on the patterns used by Black Harlemites to decorate their homes with color and imagination, often with meager means, using a technique of layering pillows and throw rugs to create shape and lend texture to space. Hills comments on the West African influence on Black southern art of appliqué quilting, layering pieces of textiles of pictorial shapes onto the fabric base of the quilt. On a quilt, fabric squares function much like Lawrence’s narrative panels.

Though Jacob Lawrence’s Nigeria series provides the framework for this exhibition, the works of many artists and writers who populated or visited both the Ibadan and Osogbo locations of the Mbari Club enliven it. Mbari grew out of a community of writers who met as students at University College in Ibadan. German writer and critic, and cofounder of Black Orpheus, Ulli Beier worked as an instructor and, as a result, met many of these writers, such as Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Christopher Okigbo as students. Obi Nwakanma in his essay “An Mbari Redivivus” points to the important novels The Palm Wine Drinkard (Amos Tutola, 1952), People of the City (Cyprian Ekwensi, 1954), and Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958) as springing from the energetic intellectual landscape of Ibadan at the time. Suggested as a name for the club by Achebe, Mbari is an Igbo word referencing creation and also referring to the traditional painted homes of the area. The Mbari movement also grew out of a flux of thought in Nigeria in the previous decades. The early 1950s saw a growing push for the revival and preservation of the traditional arts of Nigeria’s peoples. Resisting colonial ideas that linked African abstraction to “primitivism,” artists like Uche Okeke, whose Christ is featured in the exhibition, advocated for a “natural synthesis” between Indigenous traditions and Western art. The modern African artist had been undoubtedly influenced by both and could work within the scope of both traditions without self-consciousness. Okeke was a member of the Zaria Art Society. Often referred to as the “Zaria Rebels,” the members were a group of students in the Department of Fine Arts of the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology who rejected the dominance of Western thought in the teaching and producing of art at the university.

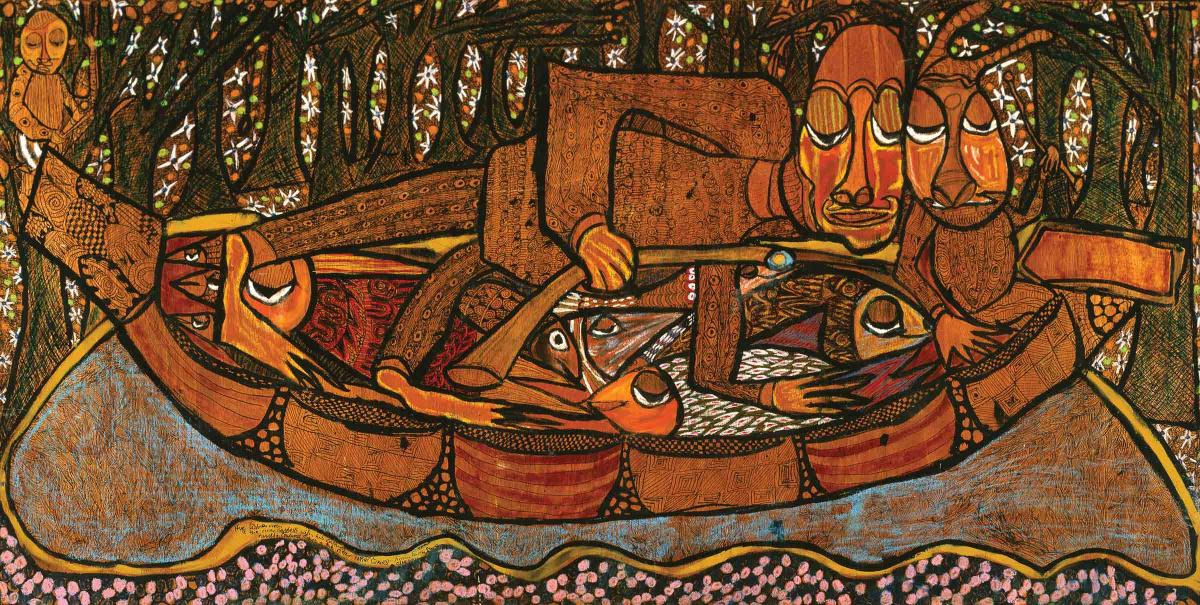

The Mbari club in Ibadan was located in the middle of the busy urban center and functioned as a gallery, center for debate, theater, and publishing house. Sixty miles away in the much smaller city of Osogbo, teacher, composer, and playwright Duro Ladipo met Ulli Beier, and together they converted Ladipo’s father’s house into an art gallery and theater. Mbari Mbayo, as this iteration of the artists and writers club was called, found its origin in the Yoruba phrase, meaning “when I see it, I shall be happy.” The Osogbo group focused on those without formal art training and hosted informal drop-in workshops. Osogbo artist Twins Seven-Seven’s The Fisherman and the River Goddess with His Captured Multicolored Fishes and the River Night Guard illuminates the city’s existence as an open-air shrine with everyday life happening in the presence of the sacred grove near the Osun River, home of the river deity of the same name.

Lawrence attended the third Mbari Mbayo workshop in 1964. In an interview with art historian Carroll Greene in 1968, Lawrence was asked if Nigerian artists identified with his work. Lawrence mentioned three groups of artists he encountered on his visits: neotraditionalists, sophisticates, and the Mbari artists. Lawrence did not have much in common with the neotraditionalists, saw the “sophisticates” as too Western, but, he said, he did feel a kinship with the Mbari artists. Their shared sense of hybridity, of working with the knowledge of being a culture in transition, and their syncretism of narrative, visual, and performing arts surely spoke to Lawrence’s thrust as a visual artist and a storyteller. Mbari Artists and Writers Club published titles by 17 African writers and acted as publisher of Black Orpheus for its ten-year run. It took its title from French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s introductory essay to Léopold Sédar Senghor’s Anthologie del la Nouvelle Poésie Negre et Malgache de Langue Française. Black Orpheus published, in English, poetry, fiction, literary and art criticism, and commentary from the continent as well as the diaspora. And while named for the Greek mythic hero, the journal featured careful translations of the sacred stories, chants, and prayers of a variety of Africa’s Indigenous peoples.

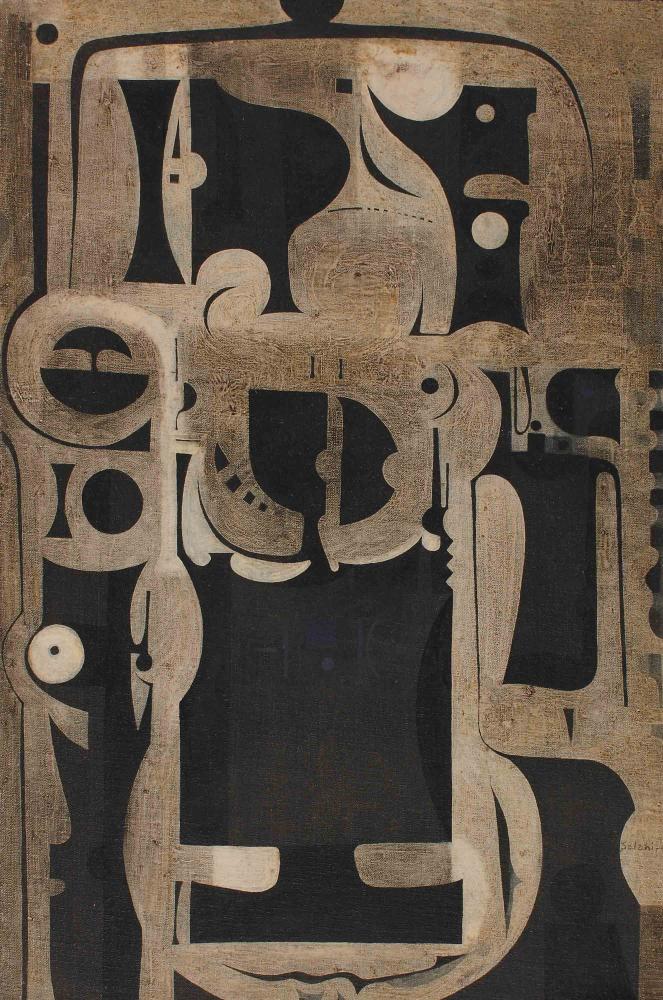

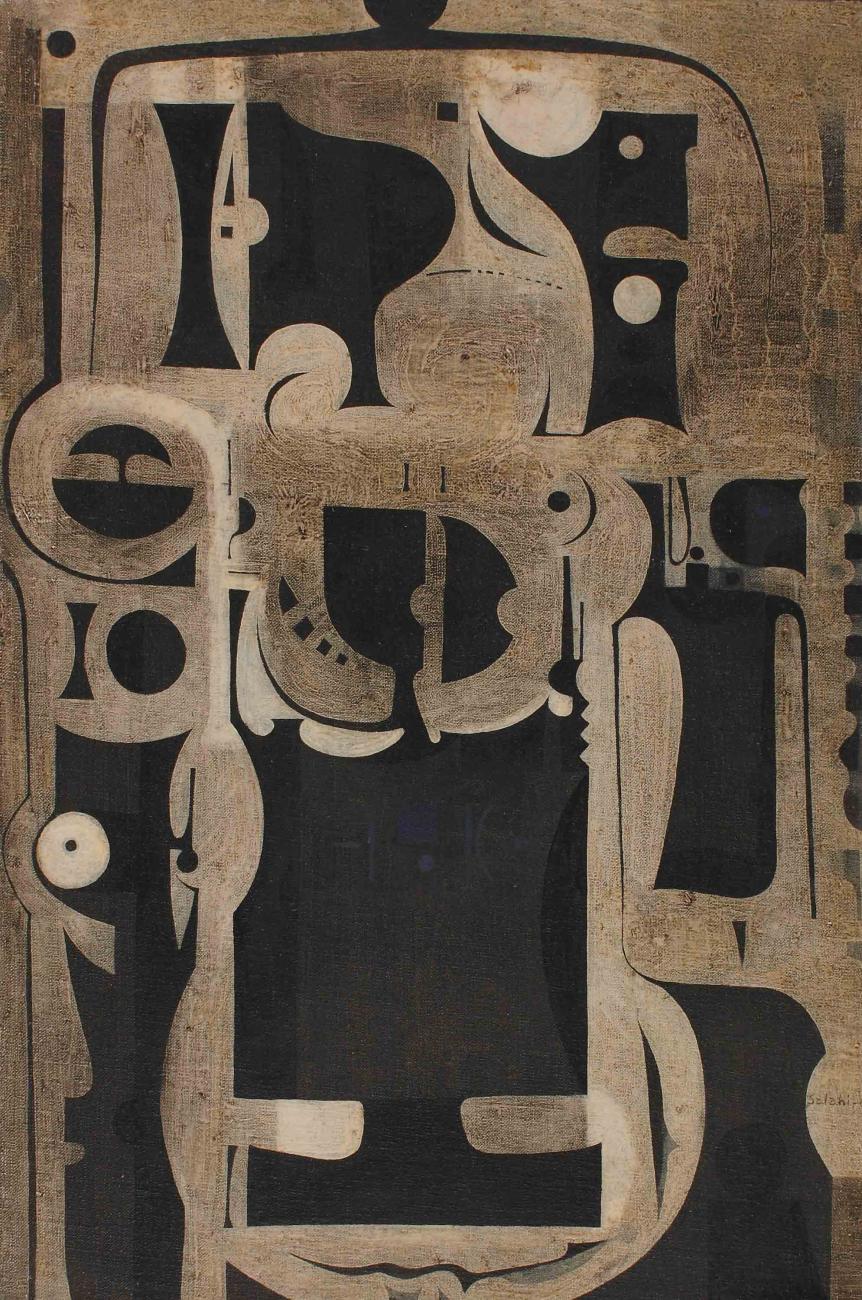

The Mbari Club’s writers and artists created and asserted their intellectual agency in the midst of a complicated political era. Seventeen African nations achieved their independence in the 1960s. As the Cold War heated up, the United States and the Soviet Union competed for influence on the continent. Black Orpheus initially received support from the Nigerian Ministry of Education. When that ended in 1961, the journal sought support from the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) for the duration of its existence. The CCF would later be revealed by media outlets as a program of the Central Intelligence Agency. The agency’s support was unknown to the Mbari Club’s writers and artists who may have benefited but remained creatively autonomous. In addition to Nigerian artists, Black Orpheus and the Mbari Club exhibited, published, and reviewed the works of other African artists such as Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi, whom Lawrence encountered on his ’64 visit, as well as Ethiopian Armenian artist Alexander “Skunder” Boghossian and Ahmed Shibrain, also Sudanese. These artists are featured in “Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club,” and their experimentation with Arabic and Coptic scripts deepens the exhibition’s close focus and reflection on the sacred relationship between spirit, image, and word.