Qui est per omnia secula benedictus are the final words of La Vita Nuova, Dante Alighieri’s collection of poetry and prose.

The Latin renders to “who is blessed for ever” and concludes an enigmatic, brief paragraph. First published in 1294, La Vita Nuova is a tantalizing prelude to the Florentine poet’s masterpiece, La Commedia, known today as The Divine Comedy. For centuries, readers and scholars have pored over La Vita Nuova (Italian for, literally, the new life)—convinced, as we often are, that a gifted writer’s nascent work contains the answers to longstanding mysteries.

La Vita Nuova’s ultimate paragraph follows a sonnet that Dante wrote for “two gracious ladies” of “noble lineage.” The poem begins: “Beyond the widest of the circling spheres / A sigh which leaves my heart aspires to move.” The sigh was a heavy one; a protracted sigh, in fact, that Dante had exhaled for much of his life. “As it nears / Its goal of longing in the realms above / The pilgrim spirit sees a vision”—a vision of Beatrice, the woman he loved for much of his life. “This much,” the sonnet concludes, “I know well.”

Dante finishes La Vita Nuova by describing that his sonnet was followed by “a marvellous vision in which I saw things which made me decide to write no more of this blessed one until I could do so more worthily.” Dante promises that he will write toward her glory, “as she indeed knows,” and he prays that God will grant him enough years so that he can “compose concerning her what has never been written in rhyme of any woman.”

Even more, Dante prays—he pleads—that “my soul may go to see the glory of my lady, that is of the blessed Beatrice, who now in glory beholds the face of Him.” As in much of Dante’s work, it is both humble and ambitious: The poet wished to join his beloved in eternity while affirming that she is in sight of the divine. The request concludes with that Latin phrase, appended with a bit of mystery: Is it God who is blessed forever, or is it Beatrice?

Was there a meaningful distinction between the two—for Dante?

In being endlessly allusive—referencing in his own verse so many people living and dead, poets and politicians, and other literary and religious works—Dante Alighieri was endlessly elusive. The man of whom so much has been written and pondered remains, on some essential points, a mystery. Cast from his home city, he would be forever in exile.

When scholars pore over the work of an esteemed writer, they often mine that writer’s juvenilia and private correspondence for answers. The canonical works, the thinking goes, are so well trod as to lose their element of surprise. Yet a writer’s greener or more incidental work might unlock our understanding of the more refined creations.

A dozen or so letters by Dante exist, and some are of dubious provenance. Yet it is an undiscovered letter that is most enticing. Near the end of La Vita Nuova, after the death of his beloved Beatrice, Dante wrote a letter to the city of Florence: “After she had departed this life, the city of which I have spoken was left as though widowed, despoiled of all good, and I, still mourning in this city of desolation, wrote to the rulers of the earth, telling them something of its condition.” He quotes the opening of Lamentations 1:1, from the prophet Jeremiah, as the start of his own letter: Quomodo sedet sola civitas (“How doth the city sit solitary”), likening Beatrice to God, who had deserted a sinful Jerusalem.

Yet Dante does not include the letter beyond that opening phrase; none of his own words are repeated. He responds to the reader’s expected criticism: “My excuse is that I intended from the beginning to write only in the vernacular [in this book], and since the words which follow those I have quoted are all in Latin it would be contrary to my intention if I quoted them all.” The full letter has been lost to history. Yet paired with the final Latin lines of La Vita Nuova, the hidden letter captures a paradox of language. For a poet seeking to forge a fresh vision through a new vernacular, he remains transfixed by an ancient tongue and tradition.

This suggests a powerful reason for why we should continue to read and think about Dante, over 700 years later: His story is not over.

Dante Alighieri gave a shape to Hell, one that would be further dramatized by writers from John Milton to Jean-Paul Sartre. His grand vision of this world and beyond, articulated in the La Commedia, so permeates our modern lives that perhaps we are never merely introduced to Dante; we simply better understand how we have lived among his ideas.

Each generation of scholars brings a new cadre of Dante aficionados. His literary popularity is certainly commensurate with his skill, but Dante almost compelled himself to be studied. For every sonnet and canzone that appears in La Vita Nuova, there is an accompanying exegesis from Dante himself. At some points, he explains his structure and describes his narrative pivots. Elsewhere, he elucidates the ideas behind his lines.

It would be reductive to describe his self-commentary as merely the product of ego—however necessary ambition is to poetry. Rather, Dante’s commentary within La Vita Nuova is an affirmation of the process of poetry. Although prose is also the result of technique and revision, poetry is “the best words in the best order,” to borrow Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s pithy definition. Lineated poetry—poems with deliberate line breaks, chosen by rhythm or rhyme—requires distillation and compression of ideas. By laying bare the turns of his verse, Dante offers readers a view into the interplay between imagination and language; between idea and poetic material. His exegetical mode, a literary practice often applied to Scripture, also marks poetry as a sacred activity.

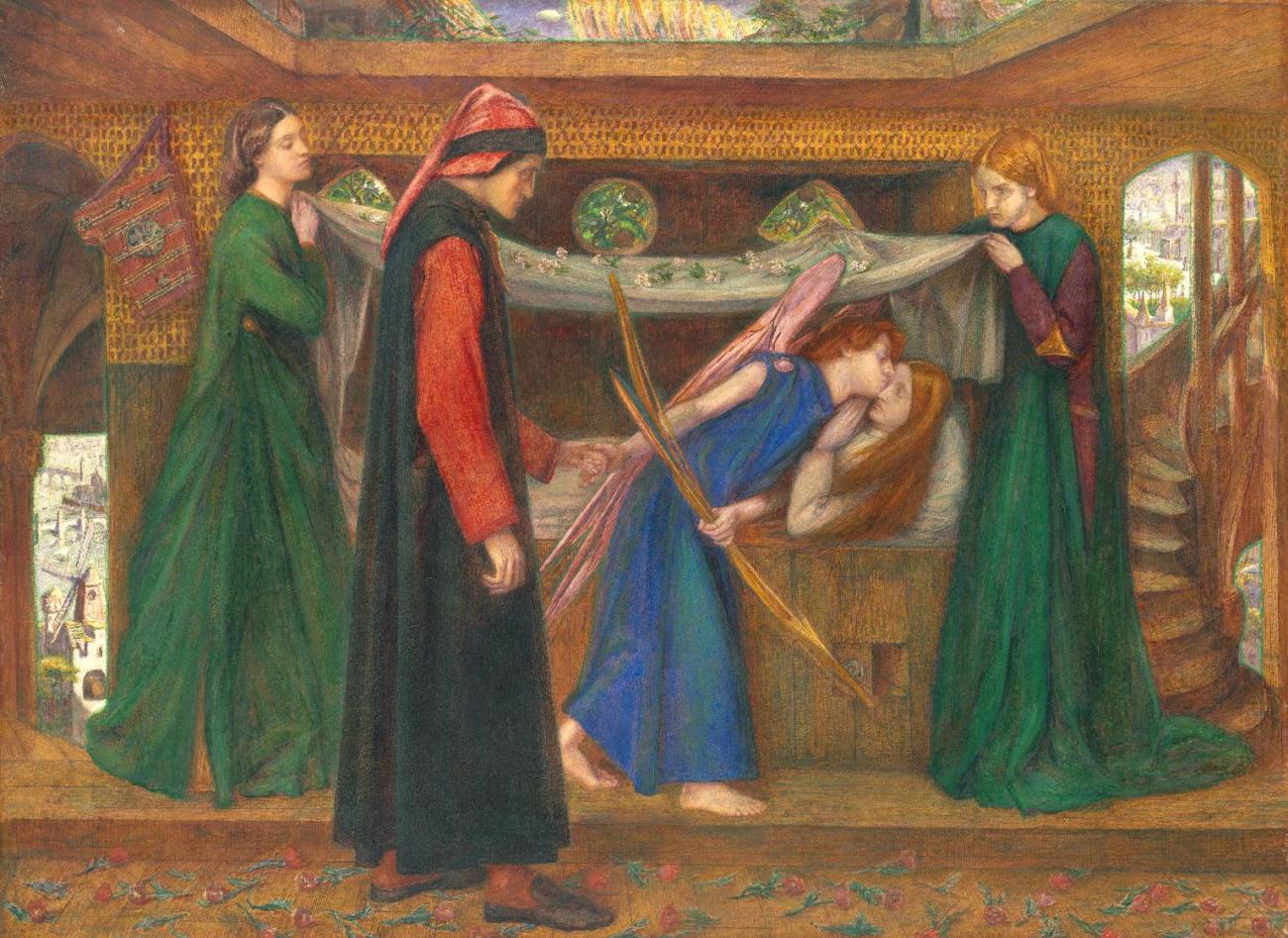

The sacred origin of Dante’s poetry was Beatrice Portinari, whom he first encountered when they were both nine years old. She was dressed in “a decorous and delicate crimson.” Dante was not merely smitten; he was transformed. During their few interactions that followed, and the many times that he thought of her, Beatrice would stir a physical reaction in Dante; a “tremble” that was obvious to onlookers. Friends observed that he “grew so frail and weak” because his “soul was wholly given to thoughts” of Beatrice. He often wept. Dante again returned to the stirrings of the prophet Jeremiah, quoting Lamentations 1:12: “All ye that pass by, behold and see if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow.”

As other poets, Dante would personify his love for Beatrice, yet he gave its identity a masculine form: “Love ruled over my soul, which was thus wedded to him early in life, and he began to acquire such assurance and mastery over me.” There was Beatrice the girl turned woman—the actual person—and there was also Beatrice the muse, vision, and idea. The third person of this trinity was Love itself, an almost poetic decision to give a physical figure to an overwhelming emotion.

Dante, of course, did not invent love poetry, and neither did he invent the singular, unattainable muse. As the American poet W. S. Merwin has noted, Dante stands in a long graduation of troubadour poetry—one that reached a particular sharpness “in the tenth-century Arabic poetry of the Omayyad Moorish kingdoms of southern Spain.” There circulated the story of the poet Yusuf Ibn Harun al-Ramadi, who became smitten with a woman named Khalwa in Córdoba who “entirely captured my heart, so that all my limbs were penetrated by the love of her.” After a short conversation, she leaves him, but he is unable to forget her: “I know not whether the heavens have devoured her, or whether the earth has swallowed her up; and the feeling I have in my heart on her account is hotter than burning coals.”

Dante’s canzone upon the death of Beatrice inherits this metaphorical tradition: “Tears of compassion for my grieving heart / Such torment have inflicted on my eyes / That, having wept their fill, they can no more.” He writes that Beatrice has “suddenly departed” to Paradise, not because of some prosaic death, but because of a patently divine desire. Her soul “pierced the heavens with its radiance,” so much that “God was moved to wonder at the same / And a sweet longing came / To summon to Him such benevolence.”

Not even God could dispute Beatrice’s beauty and presence. Dante ascribes to Beatrice an almost incarnational presence. Such a deep love bursts at the seams of his sonnets. Her story was grander than short verse might contain, prodding Dante to write the longer works that etch him into history.

Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso are spiritual, timeless works, yet they arose from the pen of a particular man, exiled from a specific place. Such a framing is at the core of Dante, an expansive, two-part documentary by Ric Burns, set for a March 2024 release. Burns’s film, a project funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, suggests that Dante’s two great longings—for Beatrice, and for the city of Florence—nourished each other. Dante’s distance from both became the most bittersweet, and ripest poetic fuel: an ardent longing that could never be satiated.

The first quarter of the film dramatizes Dante’s civic and political life, including his rejection of Pope Boniface VIII’s desire to control Florence. The fractured city was torn between warring factions: the black Guelphs, whom Dante scholar Guy Raffa notes “benefited economically and politically from strengthening traditional alliances with the papacy,” and the white Guelphs like Dante, who rejected papal “ambitions.”

On June 13, 1300, Dante was elected to a two-month term as one of the city’s six ruling priors. Two years later, Dante was condemned to death by the black Guelphs, who had gained power. If the poet ever returned to Florence, he would be burned at the stake. This was no mere historical footnote; it was the spark that began a poetic flame.

Inferno is set during 1300, and Burns generously engages the poem’s text. He features interviews with scholars of the poet, including Riccardo Bruscagli (who co-wrote the film with Burns) and Heather Webb of the University of Cambridge. Throughout the film, Webb can be seen unpacking lines and cantos with Fattori Fraser, who plays Beatrice in the film. Dante is portrayed by Florentine Antonio Fazzini, who tells the filmmakers that to be from Florence means to be “conscious” of Dante one’s entire life.

For Fazzini, Dante was the man who “invented” Florence. When the actor was two years old, constant rain sent the Arno cascading into the city. Over the course of two days, the city was ravaged by the flood: Residents drowned, hospitals lost power, roads were impassable, and the celebrated Piazza del Duomo was underwater. Scores of rare works of literature and art were destroyed. In the Piazza Sante Croce, Bruscagli recalls how water rose over the pedestal of Dante’s statue.

Burns’s decision to feature Fazzini and Fraser in dramatized moments—where they depicted narrated cantos in character—and in these scenes of preparation and process was an inspired one. In the same way that Dante laid bare his technique next to his creations in La Vita Nuova, the film invites viewers into appreciating the transformative craft of the documentary.

Dante notes the essential role of women in forging the poet’s journey through Hell. In the second canto, Virgil shares that Beatrice herself, who describes Dante as “my dearest friend,” enlisted the Roman poet to “help him, and solace me.” Beatrice succinctly tells Virgil: “Love called me here.” Additionally, the intercessions of the Virgin Mary, Saint Lucia, and Rachel buoyed Dante as he “entered on that hard and perilous track.”

A mere mortal, Dante is certainly in need of guidance in Hell. At the end of the third canto, “Blind, // like one whom sleep comes over in a swoon,” he “stumbled into darkness and went down.” His frailty there recalls his trembling before the sight or thought of Beatrice in his own life—perhaps a subtle acknowledgment in the text that she will be the conclusion of his journey.

That conclusion remains at the forefront of the film, and for good reason: Inferno is an itinerant text, the opening of a trinity. Although it is a visceral masterwork, replete with unforgettable and jarring images, Inferno is a first step. Purgatorio, however, is the book of La Commedia that most moved the poet W. S. Merwin. Born in Union City, New Jersey, in 1927, the son of a “strict, unemotional” Presbyterian minister, young Merwin found his poetic sense stirred by his father’s readings of the King James Bible.

Merwin’s father had a copy of Henry Francis Cary’s translation of La Commedia, complete with illustrations by Gustave Doré. Curious, Merwin paged through the book, reading snippets and savoring the drawings. Years later, Merwin recalls that poet and editor Daniel Halpern solicited contemporary poets to translate sections of Inferno. Merwin was at first skeptical, but he became enamored with the process as an act of communion. “Without realizing it,” he wrote, “I was already caught.”

In the foreword to his translation of Purgatorio, Merwin lauds its distinctive nature: “Of the three sections of the poem, only Purgatory happens on the earth, as our lives do, with our feet on the ground, crossing a beach, climbing a mountain.” The terrestrial world depicted in the first canto of Inferno is a proto-Hell, steeped in the surreal imagery of wilderness. Merwin’s claim, then about Purgatorio is captivating.

As a poet, Merwin was drawn to how the present is stitched to eternity. “All day the stars watch from long ago,” he begins his poem “Rain Light”: “my mother said I am going now / when you are alone you will be all right / whether or not you know you will know.” The eternal nature of the cosmos, juxtaposed with that still-eternal human emotion—love—creates a transcendent feel in his poem. The narrator affirms that “all the flowers are forms of water” as “the sun reminds them through a white cloud,” for “the washed colors of the afterlife” have “lived there long before you were born.”

Merwin eschews punctuation in “Rain Light,” his series of run-on lines creating a gentle profluence, and complicating the source of the statements. The narrator’s mother speaks in the second line of the poem, and the tenor of that assigned statement carries through the lines that follow, offering the possibility that her love is the source of the wisdom—a love that transcends death.

Our greatest freedom resides in our gesture toward eternity, and Virgil affirms Dante’s desire for freedom in the first canto of Purgatorio: “Now may it please you to approve his coming; / his goal is liberty, and one who has / forfeited life for that knows how dear it is.” Whenever Dante struggles, Virgil reminds him of Beatrice, who will set him free: “I do not know whether you grasp my meaning. / I am speaking of Beatrice, whom you will see / at the top of this mountain, happy and smiling.” Dante’s reaction is immediate: “My lord, let us walk faster, for / I do not feel tired as I did before, / and see how the hill now casts its shadow.”

In Canto 27, Virgil’s final words to Dante affirm the evolution of the poet from a melancholy, dizzy mortal to one infused with a measure of blessed wisdom: “Expect no further word or sign from me. / Your own will is whole, upright, and free, / and it would be wrong not to do as it bids you, // therefore I crown and miter you over yourself.” Yet Dante, perhaps world weary from his own exile, tempers the potential joy of Purgatorio’s conclusion. In language that recalls La Vita Nuova, Dante notes that he has not “been left helplessly undone / with awe and trembling in her presence.” He is stirred, however, by an old feeling: “the high force beat upon my / sight, as it had pierced me before I / had yet emerged out of my childhood.”

Dante is much like a child at this moment, so overjoyed that he wishes to share his feelings with his poet-father, Virgil, but his guide is gone. Dante weeps. Beatrice appears, but does not console him. Rather, she rebukes him to the assembled angels, lamenting that although “For a while I sustained him with my face,” later Dante “took himself from me and gave himself to others.” Finally, when she “had risen from flesh to spirit” and departed this earth, “I was less dear and pleasing to him.”

In real life, Dante married a fellow Florentine named Gemma di Manetto Donati—an arranged union that bore several children, yet was unmentioned in his works. They likely married before Beatrice’s death in 1290, yet Beatrice’s rejoinder of Dante in Purgatorio is certainly more a product of his poetic guilt than any reality.

Rather than negating Dante’s desire for freedom, the work’s paradoxical climax affirms a timeless, complex component of liberty: The material and spiritual elements of liberty are often in tension with each other. In May 1315, officials in Florence offered Dante a return home to his beloved city—but appended rather humiliating stipulations. Dante refused, and both he and his family were again condemned by the city.

In one of his surviving letters, Dante writes to “a Florentine friend.” Although he appreciates the invitation, and the support of his friend (“it happens very rarely to exiles to find friends”), he rejects such an ignoble return. He then shares his reasoning: “Can I not look upon the face of the sun and the stars everywhere? Can I not meditate anywhere under the heavens upon most sweet truths, unless I first render myself inglorious, nay ignominious, to the people and state of Florence?”

Dante, across so many centuries, offers us a similar invitation. We may read, and be enlightened by, his works—and even if we are far from his native and lamented home, we join him under that same sun and stars.