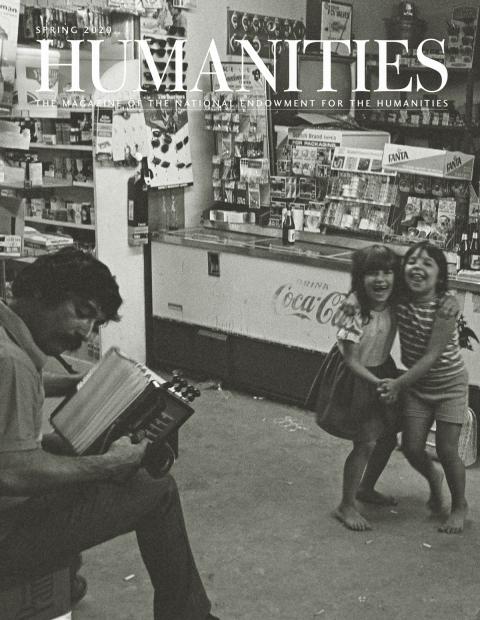

David Bruce Smith is a writer, editor, and publisher. He is also president of the Grateful American Foundation and a supporter of numerous cultural efforts, including NEH’s recent “Celebrate the Humanties” event at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

HUMANITIES: What is the mission of the Grateful American Foundation and why is it called that?

DAVID BRUCE SMITH: The purpose of the foundation is to restore enthusiasm about American history for kids—and adults.

Patriotism is a very dominant piece of the Smith family DNA. My father always referred to himself as a “grateful American”—that’s a sentiment. I decided to name the foundation after him—that is a noun. And my son, who is in the military, he is the verb.

HUMANITIES: In addition to publishing books, the foundation celebrates books by giving out awards. How did it come about and what are some of the books that have received the Grateful American Book Prize?

SMITH: In December of 2014, my friend Bruce Cole, a former chairman of NEH, suggested I create a book prize. He believed it would propel the foundation. I thought it was a great idea, so, with some help, I found a prize coordinator and decided to concentrate on seventh- to ninth-grade fiction, historical fiction, and nonfiction. I picked this niche because those are tough years for just about everybody, but I believe the benefits of reading can be akin to having a “paper psychiatrist.”

Here is a list of the prize winners: 2015: Kathy Cannon Wiechman’s Like a River: A Civil War Novel; 2016: Chris Stevenson’s The Drum of Destiny; 2017: Margot Lee Shetterly’s Hidden Figures (young readers’ edition); 2018: L. M. Elliott’s Suspect Red; 2019: Sonia Sotomayor’s The Beloved World of Sonia Sotomayor (young readers’ edition of My Beloved World). Seven judges, including myself, select the prizewinner, and the two honorable mentions.

HUMANITIES: Let’s talk about your latest book, Abigail & John. It’s a children’s book about the founding father John Adams and his wife, Abigail, but in the title Abigail comes first. Why?

SMITH: If you go to Mount Vernon or Montpelier, the signage says, “George Washington’s Mount Vernon” and “James Madison’s Montpelier,” respectively. After a while, it occurred to me that little girls were being excluded from the narrative. If that changed, they would experience these places as something more than old houses that were once occupied by men who are now dead; with a modernized context, girls might feel more engaged, and—over time—historical literacy could rise.

I gave Abigail top billing in Abigail & John because, without her, the prickly John Adams probably would not have made it to the White House. She was his confidante, savvy political adviser, beloved friend, and wife.

The next book in this series will be Dolley & James, which, of course, is about the Madisons.

HUMANITIES: Who illustrated Abigail & John?

SMITH: My mother, Clarice Smith. She has illustrated almost all my work.

HUMANITIES: Speaking of your mother, you once published a book about her paintings. It was called Afternoon Tea with Mom. Aside from the fact that she is an accomplished artist, what inspired you to create a book about your mom?

SMITH: My mother has always been my favorite artist, but, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized why: Her work is warm, impressionistic, and reflective. I’ve often said she is the Meryl Streep of artists, because each painting is distinctive and seamlessly great.

Afternoon Tea with Mom was written and produced in absolute secrecy. It was a surprise fifty-fifth birthday present.

HUMANITIES: It’s not the only instance of you creating a book about a member of your family. Around 1985, you helped your grandfather with a well-written memoir called Building My Life. Who was your grandfather, and what was that book about?

SMITH: My grandfather, Charles E. Smith, immigrated from Russia to Brooklyn, New York, in 1911. By the time he was 25, in 1926, he was a successful, small-time builder of homes and strip centers.

In 1929, he lost his money, struggled in various ventures for more than a decade, and came to Washington in 1942 for better employment opportunities. His first project—56 homes in District Heights—failed, but he found work as a construction superintendent, until he started the Charles E. Smith companies in 1946.

When he retired in 1967, Charles E. Smith was the largest and most successful real estate enterprise in the area. My father and uncle took over, and Papa Charlie devoted his remaining 28 years to philanthropy.

HUMANITIES: Your father’s name, Robert H. Smith, is well known in Washington, not only because of his work in real estate but also because of his philanthropy, which earned him a National Humanities Medal in 2008 among other distinctions. What are some of the better-known philanthropic projects he supported?

SMITH: My father believed if you were lucky enough to have the resources, then you should give back. Always a lover of history—particularly the Founding Fathers—he and my mother were donors to Founding Fathers’ homes and educational institutions such as the Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School, the University of Maryland, George Washington University, and Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

He was also president of the National Gallery of Art from 1993 to 2003 and chairman of the board of governors at Hebrew University from 1981 to 1985.

HUMANITIES: Among many other real estate ventures, he developed Crystal City in Arlington, Virginia, which has gained a lot of attention since it was chosen as the sight of Amazon’s Northern Virginia campus. What makes it an unusual place?

SMITH: Crystal City is about to become a super mecca, but sixty years ago, mixed-use projects of its size and scope didn’t exist.

When my father constructed the first building—a luxury apartment called Crystal House I—he didn’t have a master plan. “Crystal” became a city because he recognized opportunities; he was ambitious, and he garnered the confidence of his investors.

In those days, Crystal City was a wasteland, but my father believed people would cross the bridge to live there; it was near the Pentagon, Capitol Hill, National Airport, and Washington, D.C.

Always the confident visionary, my father anticipated success, but he could never have imagined Amazon fever.

HUMANITIES: Your family has been in real estate and construction since your grandfather came to the United States. And I notice that you spent a couple of decades working in the family firm but then decided to change professions, becoming a writer, an editor, and a publisher. Why? What drew you to publishing and what were you looking to accomplish?

SMITH: The company went from private to public in 2002—a new dynamic I didn’t like, but, to be fair, I decided to try.

A year later, I resigned. I told myself I had experience writing books and reviews—plus 13 years as the editor in chief of a magazine I had founded. Still, my mind demanded to know, “Now, what?”

It took awhile to figure that out.

HUMANITIES: I think a lot of people wish that someone in their family would take the time to do what you have done for your family and record a lot of the family stories, documenting not only their accomplishments but what they were like. What advice do you have for the kitchen table historian?

SMITH: Think of the subject’s history as “his—story”; that way, it’s easier to break down a life into smaller, interesting pieces. Have a few questions in mind, as a guide, and let the conversation go. Remember to record it and enjoy the experience. It can be shaped later.