In Chasing the Moon, a new NEH-supported documentary for the American Experience series on PBS, filmmaker Robert Stone tells the story of the Space Race as most Americans would have experienced it: witnessing events unfold on television, in real time. It was reality TV decades before the term existed, only the teams were nation-states, the stakes were life and death, and the prize was the moon.

Drawing from hundreds of hours of never-before-seen archival footage, Stone chronicles the early failures and eventual success of the American space program for younger generations who were not alive during the Cold War, and for whom the Space Race is merely a chapter in a history book or a few web pages on Wikipedia. For this generation, the Space Race has been mythologized—much like the Berlin Airlift or the Miracle on Ice—as the inevitable outcome of American exceptionalism. But Stone’s film reminds us that American superiority was far from a foregone conclusion when the Soviets launched Sputnik in 1957, where the film begins. The Soviet satellite, roughly the size of a beach ball, posed an existential threat to America’s status as a global military, industrial, and scientific superpower.

The Soviet Union maintained an unmistakable advantage. In the years following Sputnik, the Soviets launched the first man, Yuri Gagarin, into low-Earth orbit, conducted the first spacewalk, and landed the first spacecraft on the moon.

Meanwhile, the American public was skeptical. “There was not a groundswell of public demand for a dramatic, expensive space venture,” says historian John Logsdon in the film. “It was a leadership initiative.”

To keep the space program alive, NASA had to sell it to the American public. Their strategy was to turn it into a show and to make celebrities out of astronauts and anyone else who would help the cause.

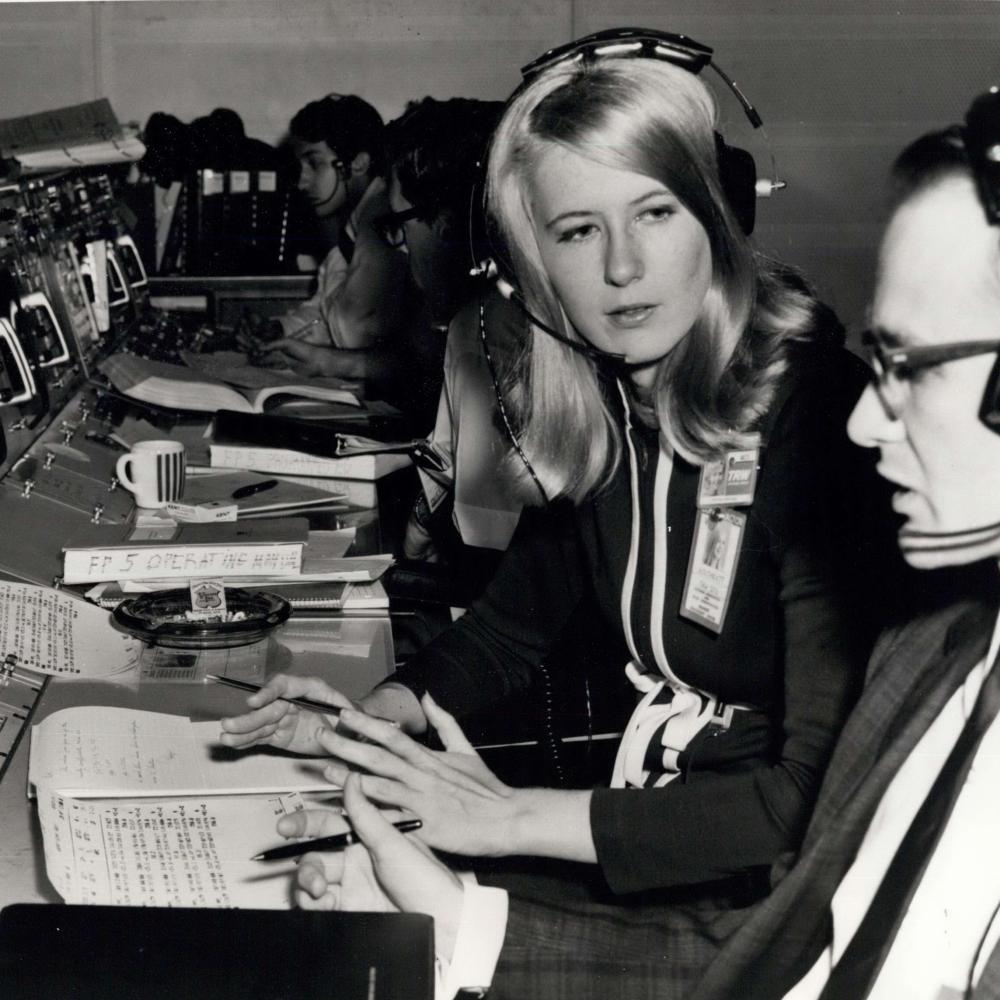

As part of the show, NASA embedded reporters with astronauts and their families, and invited them to witness training exercises, a strange new Olympics for the Space Age. NASA also placed attractive women in high-profile roles, such as Frances “Poppy” Northcutt, return-to-Earth specialist and the first female engineer to work in mission control.

“For quite a while I was the only woman in a technical role in Houston,” says Northcutt, who quickly became a fixture of the space program on television and in magazines, in Chasing the Moon. “I was sort of the trophy. I was blonde. I was young. I was thin. I wore the latest fashion clothes. Well, of course I was being used. My feeling was, you can play this both ways. The mere fact that a lot of women found out for the first time that there was a woman in mission control was a very big deal. I thought it was important that people understand that women can do these jobs.”

In 1961, Air Force test pilot Ed Dwight was selected to become the nation’s first African-American astronaut. Despite his skills as a pilot, Dwight resigned in 1966, citing “racial politics.” The space program was never fully embraced by America’s African-American communities. Amid the civil rights movement, the space program was an extravagant expenditure that did little for the cause of equality.

“We may go on from this day to Mars and to Jupiter and even to the heavens beyond,” said the civil rights leader Reverend Ralph Abernathy the day before the Apollo 11 launch. “But as long as racism, poverty, hunger, and war prevail on the Earth, we as a civilized nation have failed.”

The U.S. space program trailed the Soviet Union for a decade and public support was beginning to wane, but then, in one spectacular year, everything changed.

On December 21, 1968—less than one year before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon, and while a divided nation mourned a year of war, assassinations, and riots—Frank Borman, Bill Anders, and Jim Lovell became the first humans to leave the gravitational pull of low-Earth orbit on a trajectory for the moon.

It was a sensational media event the likes of which the world had never seen. Putting three men into orbit around the moon marked the first significant American victory of the Space Race. Upon their return, the crew of Apollo 8 were named Time magazine’s “Men of the Year,” and the achievement was celebrated with a ticker-tape parade in Times Square.

Americans were glued to their screens, following Apollo 8 on its journey. To eject itself from low-Earth orbit, the spacecraft set a world speed record of almost 7 miles per second, or 25,000 miles per hour. While in lunar orbit, Anders captured the famous “Earthrise” photograph, with the blue Earth brightly lit against the blackness of space, rising over the cratered surface of the Moon.

In a remarkable scene in Chasing the Moon, Stone shows us how that image came to be.

“Oh my God! Look at that picture over there!” said Anders. “There’s the Earth coming up. Wow, that’s pretty.”

Video footage taken from inside the Apollo 8 spacecraft shows the astronauts rushing to load film into the camera.

“You got a color film, Jim?” Anders asks. “Hand me that roll of color, quick, would you?”

A roll of film tumbles weightlessly to Anders, who quickly loads it into the camera.

“Oh man, that’s great!” said Lovell.

During a live broadcast that evening, on Christmas Eve, the crew addressed a record-breaking television audience of one billion people who were eagerly gathered around their screens for a live broadcast from the moon.

“The vast loneliness of the moon is awe-inspiring, and it makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth,” said Lovell.

It was getting late. In a few hours, it would be Christmas Day. It was time to end the transmission and send the spacecraft back home.

“We are now approaching lunar sunrise,” said Anders, “and for all the people back on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message that we would like to send to you.” The astronauts then read the first ten verses out of the Book of Genesis, though, not for any religious reason, the documentary reveals, but rather to capture the gravity of man’s first departure from the planet.

“And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you—all of you on the good Earth,” Borman said, concluding the transmission.

If there was one moment when American dominance in space finally seemed possible, when the race to the moon finally became a national unifying mission, this was it. The Apollo 8 mission was the greatest show on Earth, and we were the stars. Ultimately, its most monumental achievement may have been selling the space program to a skeptical American public, without which, the moon landing would never have been possible.

“Apollo was as much of a political and public relations challenge as it was a technical one. It takes more than an inspiring speech to undertake something as bold and aspirational as going to the moon, let alone to sustain that effort over the better part of a decade through multiple administrations,” Stone said in a recent interview with the American Film Institute. “I’d seen lots of documentaries over the years about Apollo and the space race but, as good as some of them are, I felt that nobody had ever really captured what it was like (as I remembered it) to be alive at a time when we were leaving the planet for the first time—how it impacted us here on Earth and the social and political context in which this momentous achievement took place.”