A half century after Lionel Trilling delivered the first Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, Andrew Delbanco will take the lectern under a tent on the grounds of President Lincoln's Cottage in Washington, D.C., to continue this august tradition. Tickets for the October 19 event, which are free of charge and available at neh.gov, are already being snapped up.

Trilling began his lecture in 1972 with a riff on a lesser known book by H. G. Wells called Mind at the End of Its Tether. He then turned to more optimistic views of mind and culture, including those of Thomas Jefferson, after whom the lecture is named. Jefferson believed education and a sense of history would be conducive to social equality and important for American culture in general. This gave Trilling a suitable way of talking about how a mind at the end of its tether might improve its own condition through the humanities.

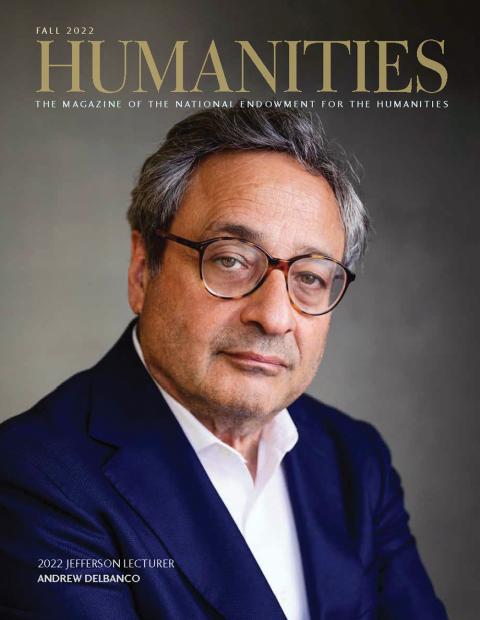

Like Trilling, Andrew Delbanco, the 2022 Jefferson Lecturer, is a professor from Columbia University. Trilling was a scholar of British literature. Delbanco is an Americanist. Both can be described as public intellectuals. In their writings, they treat the humanities as something more than a quaint old-fashioned form of higher education. More even than a set of disciplines, the humanities, both thinkers persuade you, can be a vital resource for public discussion of the deepest questions we face as individuals and Americans.

Such questions include, Delbanco says in his interview with NEH Chair Shelly C. Lowe (Navajo), what we owe each other as human beings. Delbanco sees this question not only in the matter he has taken up for his lecture—the debate over reparations for slavery—but in the history of literature from the Bible to “Bartleby, the Scrivener.”

Another classic short story discussed in this issue is “The Yellow Wall-Paper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. It, too, is about a mind at the end of its tether, but Gilman did more for American literature and politics than leave this one notch in our literary anthologies. She was a novelist, a newspaper poet, the publisher of her own magazine, and (talk about madness) the only writer for that magazine. Associate editor Alyson Foster gives us Gilman and the many stories of her eventful life.

Stories abound, too, in Brattleboro, Vermont, where a local NEH-supported effort is bringing attention to the town's rich history of literary production. Sarah Stewart Taylor takes us down the streets and alleys of the Brattleboro Words Trail.

It was also in Vermont that Ralph Ellison wrote the first sentences of Invisible Man, published 70 years ago. Eugene Holley Jr. revisits this singular novel, talking with a variety of Ellison scholars on what Ellison achieved in this one great book and, as always, why no other finished novels came after.

NEH Public Scholar Hugh Eakin writes of the exhibition by which Picasso finally conquered America. Greg Allen writes of Newark's own Noah, an ark-builder named Kea. And Sherry Lucas writes of several artists who have reinterpreted the Great Migration for an exhibition in Mississippi and Maryland.