“Nir nir nir,” that is,“me me me,” cried the woman, when Anishinaabe (Algonquin) men attacked her Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) village in the early seventeenth century. Her voice was nearly lost in the dark chaos swirling around her. It was so hard to make herself heard above the din of whooping warriors, firing arquebuses, barking dogs, and crying babies. She was desperate. She was also determined. She knew that she possessed something that marked her out and could save her from capture, slavery, violence, even death. Although she was now a woman of the Haudenosaunee, she had been a girl of the Anishinaabeg.

“Nir” was the single word she could remember from an Anishinaabe childhood that had ended when Haudenosaunee warriors took her captive. She thus repeated that word, “with all her might,” to make her would-be captor aware that she was in fact one of them. “This word saved her life.” In pronouncing that single syllable, she literally asserted her selfhood: “me me me.” More importantly, she proclaimed the significant lines of family and community that tied her simultaneously to two peoples now at war. Such connections mattered. For her, they meant life and belonging. She ended up rejoining the Anishinaabeg. She married an Anishinaabe man and had several children with him. Yet she may have spoken her native language with an accent, and she may have brought Haudenosaunee customs, from ways of making pots to ways of raising children, with her.

I was amazed when I first read this story. I was perusing the many (73 to be exact) volumes of Jesuit Relations, the published reports of the French missionaries who came to the area around the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes in the seventeenth century. This woman was never named, but her story clearly struck one of the Jesuits, Father Buteux, who wrote it down.

It is so rare for the voices of women like this one to present themselves in sources accessible to historians. Yet here was one such woman, making her voice heard over the centuries, just as she had in that critical moment of war and crisis. Her tale also showed her to be a hardy survivor, a self-sacrificing mother both to her own children and to orphans, a healer, and a skilled farmer. Women in early America did so many things. She ended up losing her Anishinaabe husband and children to epidemics that ravaged Native communities in this era, but she then became a mother to “five little children that she ha[d] saved” from an epidemic. She cultivated “a fine, large field of Indian corn.” Yet before the harvest came, hunger plagued her household. One day, Father Buteux came to find her “quite despondent and in tears.” She told him that “I have for a long time been accustomed to pass whole days without eating, . . . working in my field and taking nothing,—but I cannot hear these children cry with hunger, without being touched.” “‘This,’ said she, ‘is the cause of my tears.’” Such a claim was a powerful (and successful) way to appeal to French sympathies (tears were likely to be more effective with French audiences than with stoical Anishinaabe ones) and to gain a redistribution of resources. The French provided her with food. This account also reveals the ways in which women were relentlessly familiar with the heavy responsibilities of working in fields and taking care of children, even those of other people. Her remarkable resilience etched itself even onto the reports from the Jesuits, though her name did not.

People tend to think that colonial American women were Pilgrims or witches. Most were neither. Even if they were wives and mothers and in charge of households, as this woman was, they were not untouched by the cold, wide world. The devastations and wars, as well as the slavery and migration, of colonialism affected their worlds and lives profoundly, forcing them to do more than just raise children and keep house. Women in early America played many roles. They were survivors, diplomats, killers, rulers, rebels, and slaves. Historians have been busily uncovering this variety for some decades now, but it remains too often obscure in the popular imagination.

Pocahontas is the only colonial Native woman most Americans can name. In our current political climate, this name has become a putdown. Before that, she was a Disney princess in a scanty deerskin dress, hugging Grandmother Willow. Neither of these aspects captures the rich complexity of this woman’s trajectory. Pocahontas was a diplomat, mediator, and an important political player in her own right in the early seventeenth century. John Smith, one of the first governors of the English colony of Jamestown, claimed he would have been killed had it not been for her critical intervention. She was the daughter of a powerful leader, Powhatan. As Smith had it, “in that darke night [she] came through the irksome woods,” evidently risking her life to alert Smith and his men to her father’s plans to kill them. Smith and his crew offered her gifts of English goods to thank her, but “with the teares running downe her cheekes,” she declined, saying that “if Powhatan should know it, she were but dead.”

Smith portrayed Pocahontas’s act of filial disobedience as one of understandable love for Smith and his men, a weak woman made strong by her unexpected, but welcome, loyalty to the English. Disney has followed suit, making it seem as if Pocahontas saved Smith out of romantic love for the handsome Englishman. In fact, scholars now think her intervention was part of a highly orchestrated ritual, designed to force Smith and his men to acknowledge their dependence on Powhatan and his family, in order to integrate them into a world governed by Natives. Even after this dramatic meeting, Pocahontas’s role in this unfolding early American history was far from over. She was a cultural broker, accepting baptism (possibly under duress) as a Christian named Rebecca, and marrying an Englishman, John Rolfe. She went with him to England (again, possibly not her choice), where she was at the center of complicated diplomatic maneuvers.

Pocahontas met Queen Elizabeth I and attended masques. She even had her portrait painted, looking every inch the well-heeled lady, with a fine feathered hat and a stiff white ruff. She holds a fan, just as Queen Elizabeth did (as in the “Darnley portrait” at the National Portrait Gallery in London). You can see an engraving of Pocahontas by Simon van de Passe, as well as a portrait based on it, at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Her painting, which parallels others of Queen Elizabeth (such as Nicholas Hilliard’s “ermine portrait”) always surprises my undergraduates, who grew up on the deerskin-clad film version. This aristocratic Pocahontas demonstrates her extraordinary ability to cross cultures as an intelligent and multi-lingual diplomat and translator, able to move between worlds with grace and skill. It also shows that English people did not always see Indians as “naked savages.”

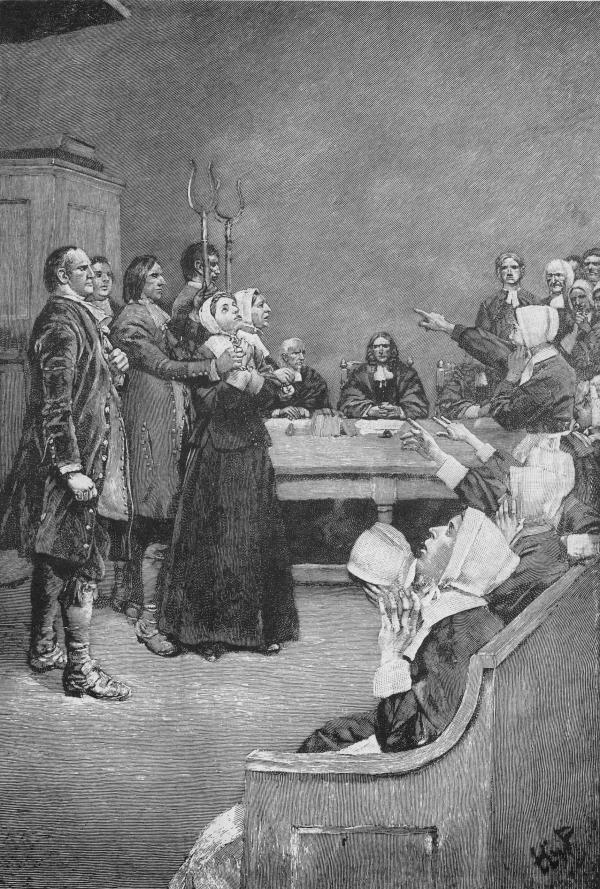

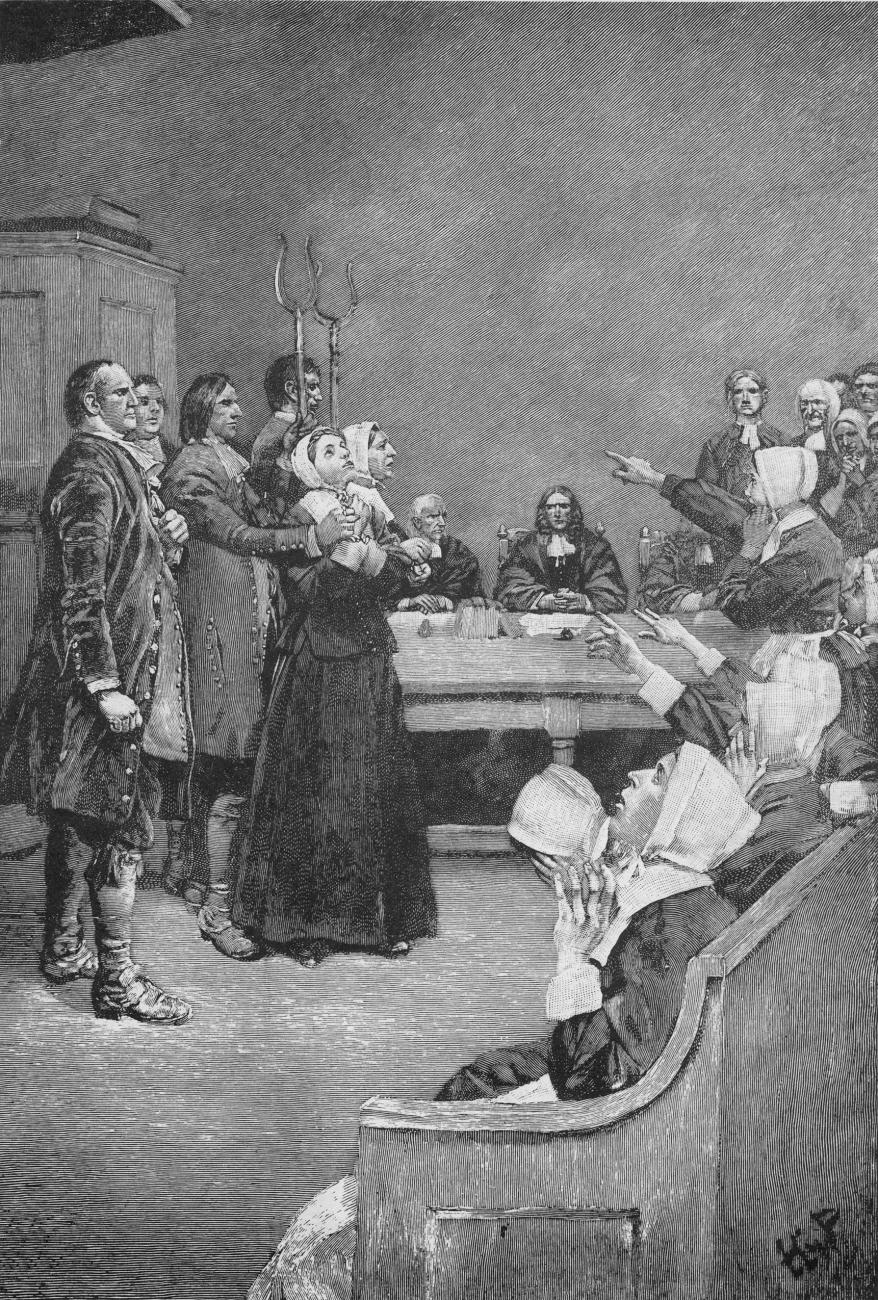

Like so many other Native Americans, Pocahontas’s life was cut short by epidemic disease, probably smallpox, contracted during her time in England. Too many other Indians died at the hands of settlers, very occasionally women themselves. One such celebrated killer was Hannah Duston, whose Haverhill, Massachusetts, house was attacked by Wabenaki Indians in a raid in 1697. According to Cotton Mather, who wrote her story, Duston had given birth only five days earlier, and warriors killed the baby. During her captivity, after marching more than one hundred miles, she organized two other captives, another woman and a boy, to attack and kill their captors: “all furnishing themselves with hatchets . . .

they struck such home blows upon the heads of their sleeping oppressors.” Ten of the twelve Native Americans in this household—two men, two women, and six children—perished in this counterattack. The mother of a slain baby thus became a child-killer herself. Yet the settlers of Boston celebrated Duston, both on her return and in their histories. It was acceptable for a woman to assume such an aggressive masculine role in times of war and crisis, when she could become a “deputy husband,” to use Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s phrase. Such role reversals were supposed to be merely temporary; the ideal remained of a household headed by a husband, with the good wife as a helpmeet.

In the normal course of life, women who appeared to overstep the bounds of wifely submission were far less palatable to New England Protestants. One such woman was Mistress Ann Hibbens, the wife of a wealthy Massachusetts merchant. She seems to have had run-ins with tradesmen as well as with her husband, William, in the 1630s. Her pastor, John Wilson, denounced her as a bad wife “against the institution of God . . . and [to] the evil example of diverse other wives.” And, concerning her husband, the pastor continued, “You have against nature usurped authority over him, grieved his spirit, and carried yourself as if he was a nobody, as if his wisdom were not to be compared to yours.” When Hibbens justified her actions on the basis that, in Genesis, God had commanded Abraham to “hearken unto” his wife Sarah, this defense only got her into more trouble. Wilson berated her: “You have . . . [also] expressed it to be your judgement that husbands must hearken unto their wives and be guided by them in all things.” For her insolence, she was excommunicated, forbidden to communicate with any but her immediate family, “for the destruction of your proud flesh [and] for the humbling of your soul.”

Another Sarah provoked New England authorities a few decades later in 1668. This wife and mother of four, Sarah Ahhanton, appeared in court, defending herself against charges leveled by her aggrieved husband that “shee did sometimes speak alone with Joseph, a married man.” Although her husband had “corrected” (that is, beaten) her repeatedly, she continued to meet with Joseph. A few weeks later, Sarah and Joseph ran away. However, Sarah was a Christian Indian who had married and lived under English law. New England settlers did not allow divorce for unhappily married couples, but Native laws did. So when Sarah and Joseph absconded to a nearby community of non-Christian Indians, they seemed to be rejecting both her marriage and English law. To some English people, here was proof that even “civilized” Christian Natives might return to “barbarity.” In fact, Sarah eventually came back to her husband and begged forgiveness for her “sinne” from him and New England magistrates. For Christian Indians and others, her story then became one of redemption, though she was punished with a severe whipping and public shaming. All kinds of missionaries in all kinds of places worked to impose Christian models of gender organization, marriage, and child-rearing on Native women and men. Francis Le Jau, a clergyman for the Society of the Propagation of the Gospel in South Carolina in the early eighteenth century, declared that “I also tell them whom I baptize, The Christian Religion does not allow plurality of Wives, nor any changing of them.” Some Indians like Sarah Ahhanton seem to have accepted such mores in theory, although they did not always live them in practice. Others rejected them outright, sometimes with violence.

Le Jau directed his message of Christianity and monogamy at both Native Americans and African Americans. Yet Anglo-American law did not in fact recognize marriages, common though they were, between enslaved people. African women suffered twice over in slavery. The Atlantic slave trade dramatically altered the nature of slavery; it also transformed the nature of marriage and family life. In the British colonies, especially, slavery came to be a matrilineal system, in which children inherited the condition of slavery from their mothers. This situation depended on an older understanding in English law in which illegitimate children traced descent through mothers. This posed unique challenges for enslaved women and their families. Enslaved women suffered vulnerability to violence of all sorts, including sexual violence. Too many masters, overseers, and others viewed such women as “nasty wenches,” sexually available, regardless of their consent or family situation. Their children, some the result of force, then inherited their grim condition of slavery. An enslaved husband lacked power to stop a master from raping his wife or selling his children. An enslaved wife could not protect herself or her children from violence or separation.

Enslaved African-American men and women, however, could and did act as husbands and wives, to protect and build their families. Even masters and mistresses recognized marriages among enslaved people, even if the law did not. Ads for runaway slaves placed by masters seeking their return refer to a husband suspected of “lurking” around the plantation where his wife lived. The grim reality of violence, sexual and otherwise, and enforced separation, as well as their omnipresent spectres, imposed a particular burden on these families. Yet family life could flourish among enslaved people, ameliorating at least some of its horrors. On September 30, 1739, an eighteen-year-old Virginia-born woman named Moll ran away with her Angolan husband, Roger. They escaped with only the clothing on their backs; Moll was “very big with Child.” In this case, it is likely the couple was eager to start a family in freedom, and their flight was prompted by her pregnancy. The master who advertised for their return a month later was subsequently the father-in-law to the revolutionary patriot who demanded “liberty or death,” Patrick Henry. But Henry was hardly the first Virginian to make this challenging choice.

Languages of liberty and slavery underpinned American political and domestic orders; connections between the two were sometimes uncomfortably close. When the marriage of a New Hampshire couple, Eunice and John Davis, broke down in 1762, John placed an ad in the local newspaper to disavow any debts his wife contracted in his name: a common practice at the time. He also took the opportunity to denounce Eunice’s behavior publicly, complaining that she “has absented herself from me, without just Cause, and refuses to live with me, tho’ often requested, and has left three small Children in a very unnatural Manner.” Rather surprisingly, Eunice herself then replied publicly: “If I am your Wife, I am not your Slave, and little thought when I acknowledg’d you as my Husband, that you would pretend to assume an unreasonable POWER to tyrannize and insult over me; and that without any just Cause.” In distinguishing between marriage and slavery, and launching critiques of tyranny in household relations, white women, in particular, carved out new opportunities for themselves well in advance of the American Revolution, which would put tyranny in the spotlight. Yet race came to matter in new and pernicious ways. In part, expanded prospects for some women depended on constrained ones for others. New household configurations underpinned novel orders of gender, race, and power. Some women, namely white ones, were considered ineligible for slavery, while others, whether Native American or African, were considered “naturally” suited to it. For them, tyranny and insults were the order of life, though all too rarely could they document and make public their unhappiness.

Some me’s, then, remain all too hard to hear. Women like Eunice Davis could by the end of the colonial period register discontent, at least occasionally, in newspapers, letters, and courts. Others, like Moll, could not do so very easily; they lacked the ability to record their tales for posterity. Ads for runaways, condemning their flying feet, remain one of the few available sources for their difficult lives. This differential access to power through records, as well as the chaos of history, means the terrible loss of significant stories and sources. Still, those me’s and their rich contexts, however faint, are important, even when—perhaps especially when—they are muffled. As the tale of the Anishinaabe widow suggests, catastrophe, epidemics, war, and mobility upended families and communities, but they did not obliterate them. Women persisted in working hard to protect themselves and their families and to assert their rights and their selfhood, even as structures of law, slavery, and colonialism arrayed against them.

A longer version of this essay appears in The Oxford Handbook of American Women’s and Gender History, eds. Ellen Hartigan-O’Connor and Lisa G. Materson.