The contemporary art exhibition “A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration” brings new dimensions and perspectives to the twentieth-century mass exodus of Black Americans out of the American South. Approximately six million Black people moved to the North, Midwest, and West between 1910 and 1970, changing the national cultural landscape forever. But this exhibition’s power lies in the family stories it presents.

The Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson and the Baltimore Museum of Art co-organized the exhibition, asking 12 acclaimed Black artists to think about their relationships to the Great Migration, its influence on their ancestors and families, and what hasn’t been said in narratives surrounding it. Themes of refuge, agency, community, memory, and speculation (when needed to fill in gaps of knowledge) thread through the works. Storytelling is at the core.

African Americans moved out of the South for a variety of reasons—to escape poverty and prejudice, to flee from physical danger, to find a better life. The most famous visual telling of the story is Jacob Lawrence’s The Migration Series. But that was a historical depiction; the current show is something different. It’s about how the effects of migration ripple through generations.

“There are all these histories to unpack that I don’t think we had entries into,” said Ryan Dennis, Mississippi Museum of Art chief curator. “It has really been profound to see how these artworks, how these artists, have allowed us to unearth more curiosities and questions about ourselves.”

New Orleans-born and Baltimore-based artist Akea Brionne’s jewel-embellished jacquard tapestries breathe life into ancestral images. An Ode to (You)’All salutes her great-grandmother and great-aunts—the Phelps sisters in Columbus, Mississippi. These matriarchs, all teachers, alternated each summer caring for their children while the others pursued degrees. Their sacrifices and the schoolhouses they built helped create opportunities for family members and community youth. “Education was a huge, huge pillar in my family,” Brionne said in a conversation with viewers.

Memory, spirituality, ritual, and a strong lineage of self-sufficiency imbue The Double Wide by Chicago artist Theaster Gates Jr. in an installation that recalls his boyhood summers in Mississippi and his uncle’s trailer, which was a candy store by day and a juke joint by night. A video with music from his own ensemble, The Black Monks, plays inside the neon-lit trailer room, where canned and pickled goods line the wall.

Oregon-born, New York-based artist Carrie Mae Weems’s haunting and hypnotic video installation Leave! Leave Now! shares the family trauma of her grandfather Frank Weems’s disappearance through narration and Pepper’s ghost effect. The latter, a nineteenth-century illusion technique used for apparitions in theaters and cinemas, here amplifies the phantom threads of Weems’s story and the funereal mood. The Arkansas sharecropper and union organizer, beaten and left for dead by a white mob in 1936, escaped to Chicago on foot and hid his identity for safety. The effect of his absence on his wife and eight children is described in a tally of the missed moments—family gatherings, dinners, dances, births, and deaths.

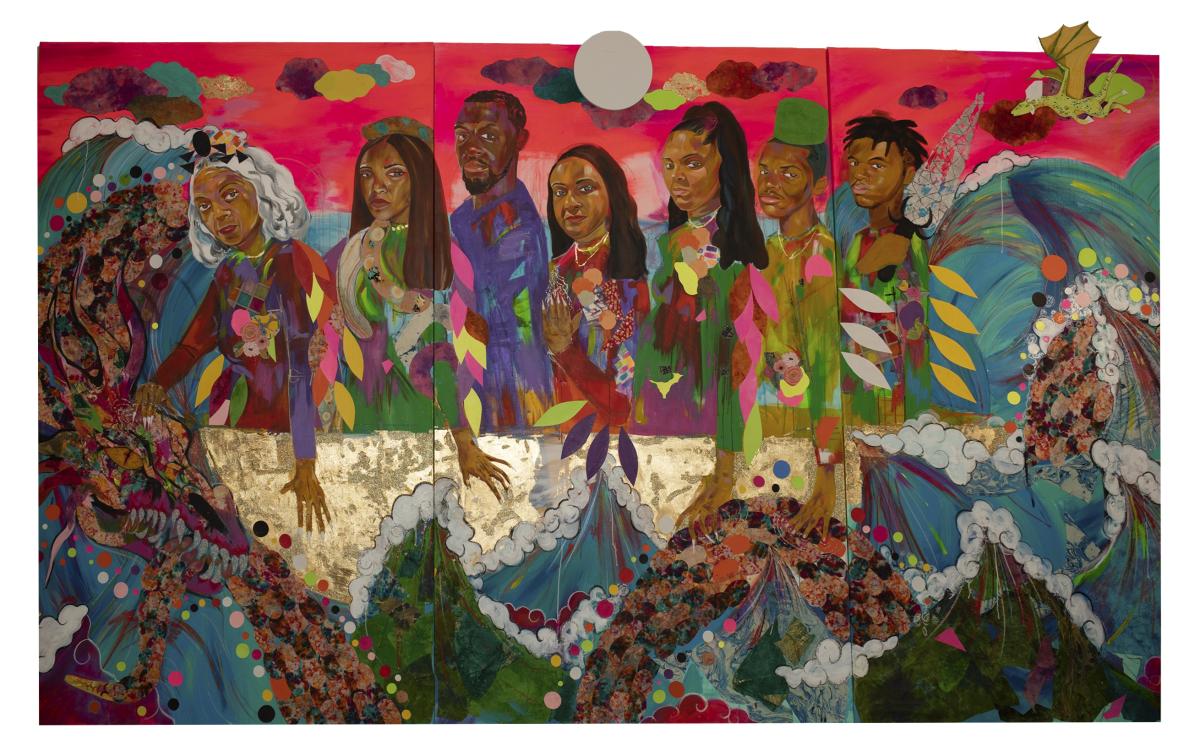

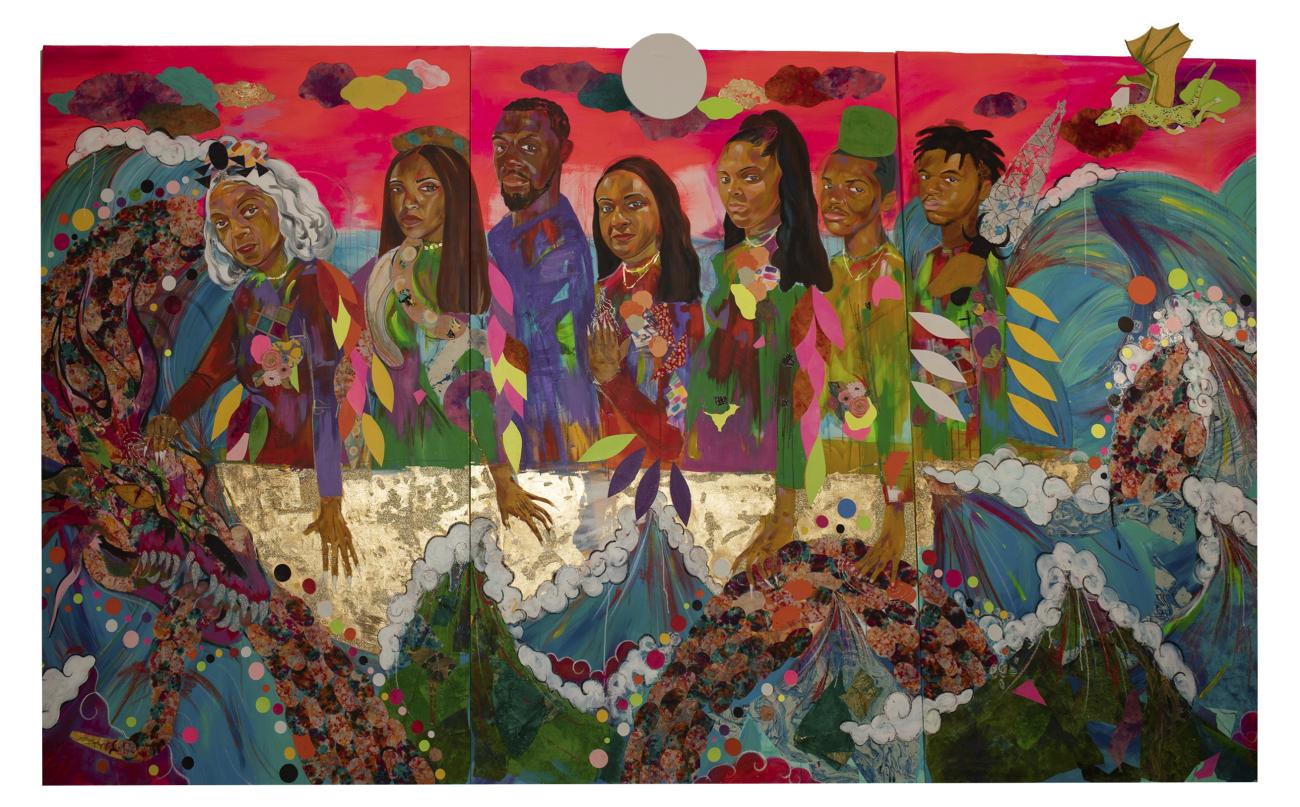

This Water Runs Deep, an epic and vibrant triptych by Detroit-born Jamea Richmond-Edwards, turns family history into a mythic journey of survival. After displacement from family land by the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, Richmond-Edwards’s family moved north to Detroit. Instead of better opportunities they found more challenges. Intimidation and dubious policies in the wake of natural disasters helped municipalities seize the family’s property back in Mississippi.

Los Angeles artist Mark Bradford’s large-scale 500, inspired by a 1913 advertisement in the NAACP magazine The Crisis, repeats the ad’s call in 60 oxidized panels that form a grid covering an entire gallery wall. “WANTED,” the ad trumpets, calling for “500 Negro families (farmers preferred)” for settlement in Blackdom, New Mexico, with the prospect of “fertile soil” and “no ‘Jim Crow’ Laws.”

“There are these really beautiful epiphanies, when one realizes about these freedmen’s towns—that there are possibilities of creating something anew from nothing, and our ancestors have time and time and time again done that,” Dennis said.

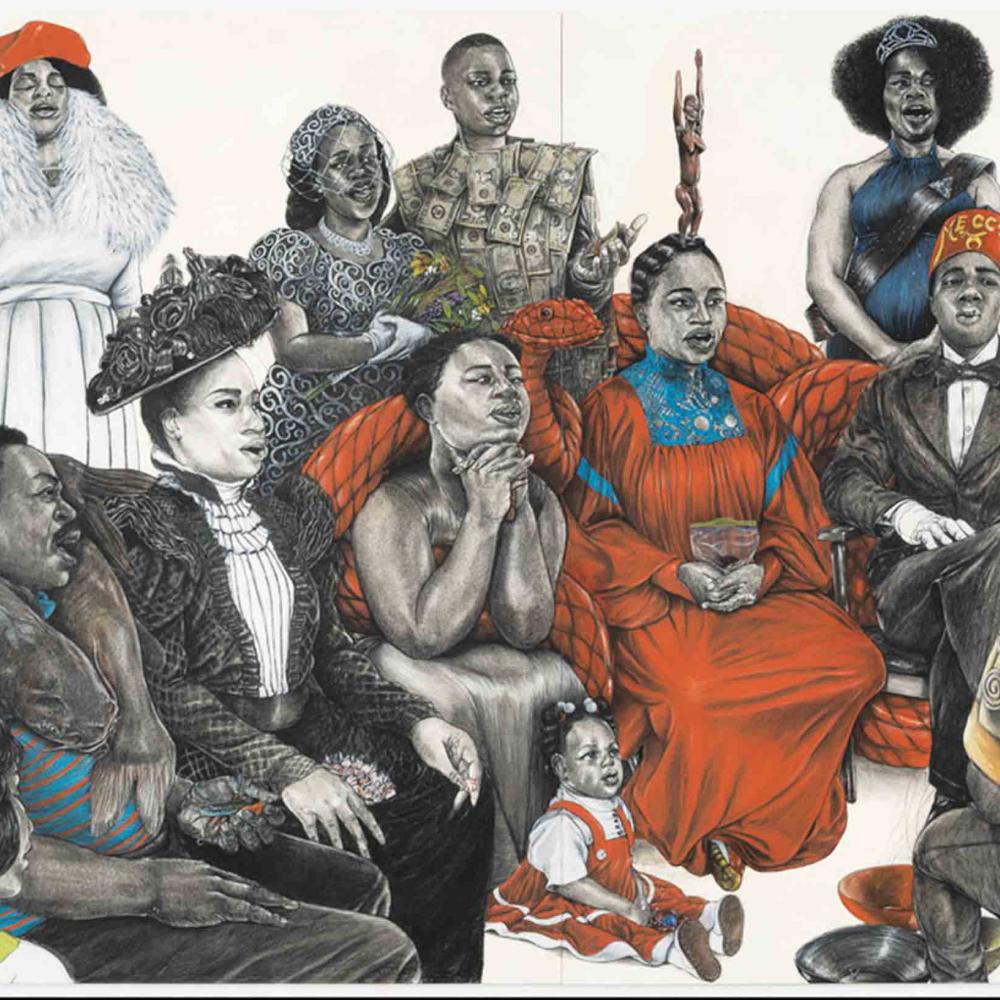

Works by these artists, and by Zoë Charlton, Larry W. Cook, Torkwase Dyson, Allison Janae Hamilton, Leslie Hewitt, Steffani Jemison, and Robert Pruitt, mark an important investigation into a period that profoundly shaped America, said Jessica Bell Brown, curator at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

“They offer us, as a country, an opportunity to think about that rapid transformation from 1915 to 1970,” Brown said, “and to think about the resilience of many Americans, Black Americans, who have been largely oppressed and disenfranchised, and then also those who found agency, despite hardship. This collectivity of artworks really tells those stories with deep nuance and reverence.”

Viewers are often inspired to better understand their own family stories, Dennis said, and encouraging youth to explore those histories with elders has been particularly meaningful. “It just grounds their sense of self and possibility in the ways that they navigate in the world.” The exhibition’s “Roots and Routes” storytelling platform provides an avenue for visitors to share their own migration stories. The exhibition’s companion book, A Movement in Every Direction: A Great Migration Critical Reader, offers additional context, exploring the movement’s impact through historical and contemporary images and writings.

The exhibition, supported by the Mississippi and Maryland humanities councils, was first presented at the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson, with dozens of accompanying public programs. “A Movement in Every Direction” opens October 30 at the Baltimore Museum of Art and remains on view through January 29, with additional venues to be announced later this fall.