The 1960s and 1970s produced seismic shifts in American popular culture that can now be felt on a global scale. One major epicenter was downtown New York City, where the inhabitants of a roughly one-square-mile area of Lower Manhattan changed the way we think about music, art, performance, and human sexuality. These events were set in motion by a tight-knit creative community that made sparks fly as its members brushed against each other.

***

Midtown was the original location of Warhol’s studio, the Factory, which was known for its silver spray-painted décor, electric atmosphere, and eclectic cross-pollination of people and scenes. The studio’s name was inspired by the artist’s assembly line-like production of silk-screen prints and, a bit later, underground films and music. Unlike many critics of mass culture during that time, Warhol didn’t draw distinctions between the downtown’s “purer” kinds of artistic expression and the “commercial” products pumped out of these midtown office buildings. This flattening of cultural distinctions helped usher in a new postmodern aesthetic.

***

Growing up during the Depression in a working-class immigrant family near Pittsburgh, Warhol spent much of his early life on the outside looking in. The seductive world of consumer goods remained out of his reach as a child, and as an adult he found himself shut out of the fine art world because of his advertising background. Warhol’s first published drawing was, appropriately enough, an image of five shoes going up a “ladder of success,” published in the summer of 1949 issue of Glamour. By the 1950s, Warhol had established himself as a successful commercial illustrator—a profession that clashed with prevailing notions of what it meant to be a “real” artist.

Abstract Expressionism, which was exemplified by hard-drinking macho painters such as Jackson Pollock, dominated America’s postwar painting world. Its frenetic, expressive style was celebrated by American and European critics as the authentic, spontaneous eruption of the human spirit—an antidote to the deadening standardization of popular culture that Andy grew up with and admired. If Pollock’s drip paintings communicated a wild emotional intensity, Warhol’s silk-screen prints were deliberately flat and deadpan, the antithesis of the Abstract Expressionist aesthetic.

As was often the case throughout his career, Warhol was more a popularizer than a pioneer. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, artists Jasper Johns and his boyfriend Robert Rauschenberg were already pushing back on the art world’s informal ban on real-world objects by painting familiar things like flags, targets, and maps. They made their work under the influence of their friend, composer John Cage, who encouraged others to incorporate chance methods and mundane materials from mass culture into their work. During this time, historian Sally Banes noted, artists turned their attention to everyday life: “It had become a symbol of egalitarianism, and it was the standard stuff of avant-garde artworks and performances.”

Downtown artists not only reoriented the taken-for-granted sensibilities of the New York art world, they also shifted its center of gravity away from the established uptown galleries—much as Off-Off-Broadway did. Over the course of the 1960s, several important galleries opened in Greenwich Village and, a bit later, in what became known as SoHo.

By 1962, the term Pop Art was being applied to work produced by the likes of Claes Oldenburg, Roy Lichtenstein, and its poster man-child, Warhol. Pop Art’s buzzy, glowing sheen fit the cultural mood of the day, when the consumer economy exploded with color and abundance. This public interest intensified after Warhol’s first solo show at the Stable Gallery in November 1962, which featured his silk-screened Marilyn Monroe portraits, Coca-Cola bottles, and other works that became iconic. Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Henry Geldzahler threw a party the night of the opening, attracting art-world heavy hitters and popular writers such as Susan Sontag and Norman Mailer. Ivan Karp, who later founded one of SoHo’s first galleries, was the event’s DJ. He played the Shirelles, the Crystals, and other Brill Building pop hits while Jasper Johns did the twist.

Pop Art ran counter to the serious sensibilities of Ab-Ex painters, who treated commercial culture with contempt and thought Warhol’s work was vapid and commercial (he was happy to be guilty as charged). “I think Andy Warhol comes out of exhaustion,” said Judson Poets’ Theatre director Larry Kornfeld. “The Abstract Expressionists’ work is based on energy, the output of energy, and Warhol was a depletion of energy to a point where it’s quite fascinating. Andy’s work is basically despairing, and the Abstract Expressionists are very joyous.”

“My personal impression was that Andy was of a different world,” Kornfeld added. “Andy was just somebody on the scene who did his thing. My friends were almost all Abstract Expressionists—Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg—and I never considered Warhol of their quality, though it was quite clear he was being very successful in doing everything in a way that made himself successful. So there’s two ways you can look at that kind of work. You can be very judgmental and put them down or you can just accept them for who they are. I think a lot of people resented his success.”

For some of the chest-beating, chin-massaging painters whose work was quickly being supplanted by Pop Art’s new guard, Warhol’s persona was too fey to be taken seriously. (This was another criticism Warhol never bothered to counter.) The disdain many felt for Warhol wasn’t necessarily driven by homophobia; it was more a clash of sensibilities. “The Abstract Expressionists tended to be heterosexual, but the great champion of the Abstract Expressionist movement was poet Frank O’Hara, who was gay and somewhat swishy,” Kornfeld said. “The Abstract Expressionists had nothing against gay people. I think the painters of that period were very, very serious—heavy drinkers, serious, sexual—and Warhol was basically a-sensual and asexual.”

***

Warhol’s connection to the underground poetry world intensified when Gerard Malanga, a poet who also had a background in commercial painting, became his primary printing assistant in the summer of 1963. The two began working together in an uptown studio near Warhol's brownstone home until the artist needed a larger studio, leading to his acquisition of a space in a midtown industrial building that became the Factory. By this point, Warhol had shifted from creating paintings with brushes—as he did with his famous Campbell’s soup can series—to his mass production-inspired silk-screen prints.

By many accounts, Warhol was inspired by the amateur techniques used to make the experimental films, mimeographed poetry zines, and Off-Off-Broadway theatrical productions he was taking in. He then applied this DIY approach to his own messily printed silks-screens. “The spirit of the aleatory, that is of John Cage’s chance operations, which Cage featured in his compositions, came into play in these early silk-screens, when talent overwhelmed technique,” recalled poet Ed Sanders.

***

On June 3, 1968, an unhinged radical and aspiring playwright named Valerie Solanas entered the Factory and shot Warhol in the chest multiple times, nearly killing him. (“Taylor [Mead] told me once that if Valerie hadn’t done it,” playwright Robert Heide recalled, “he would have.”) The shooting was a symptom of the wider chaos that was spreading through America at the time, along with trouble that was brewing in many parts of downtown.

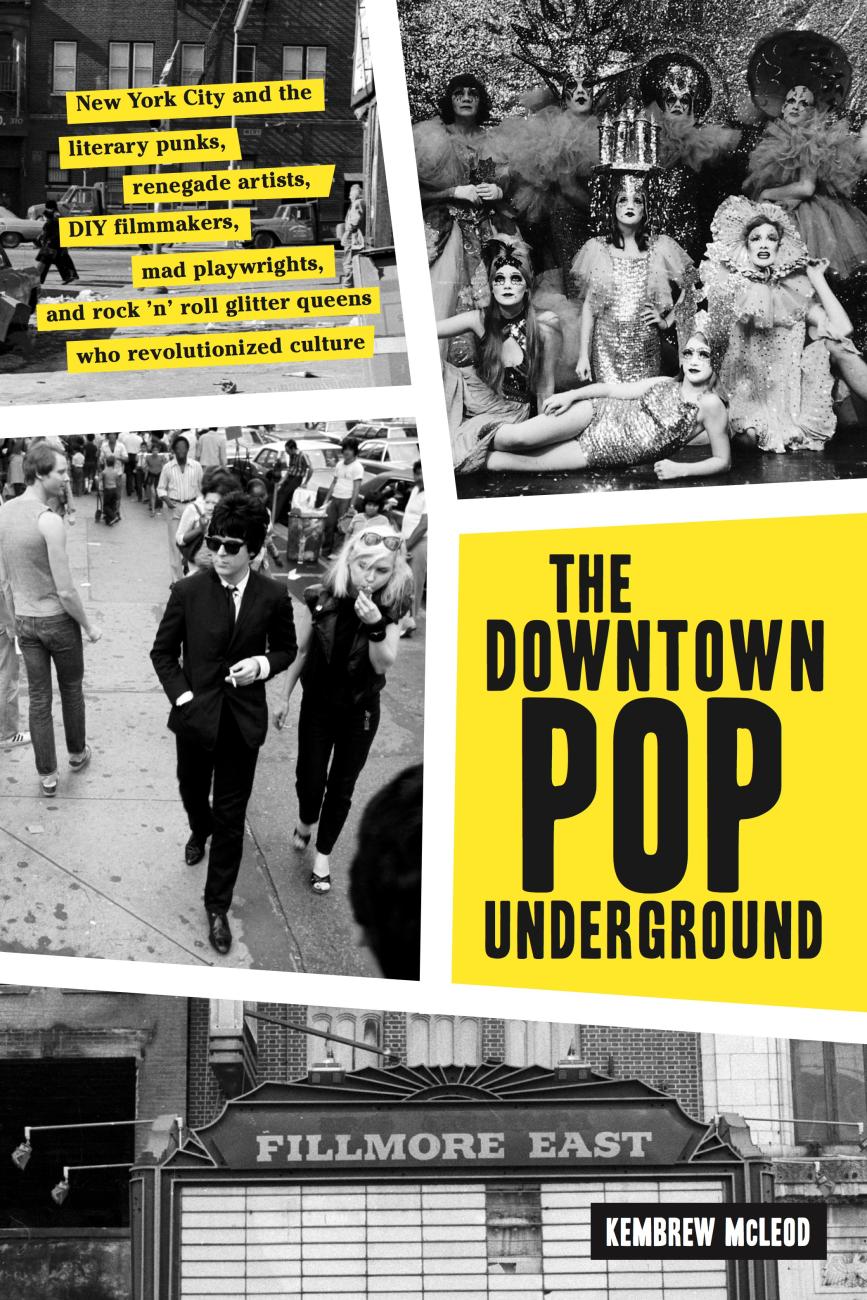

Excerpted from The Downtown Pop Underground: New York City and the Literary Punks, Renegade Artists, DIY Filmmakers, Mad Playwrights, and Rock ’N’ Roll Glitter Queens Who Revolutionized Culture by Kembrew McLeod, published by Abrams Press; text copyright © 2018 Kembrew McLeod.