In unseasonably warm August 2019, two NEH colleagues and I traveled some four thousand miles across Alaska by airplane and auto, train and boat, ferry and foot, but barely scratched the mineral-rich surface of the forty-ninth state.

Learning about the history and culture of different states and territories is an honor. It is also a chance to see, for myself, the programs and institutions NEH is supporting.

Our weeklong trip took us first to the state’s largest city, Anchorage, to tour vibrant cultural organizations funded by our agency and our state partner, Alaska Humanities Forum (AHF). I cannot overstate the kindness of AHF president Kameron Perez-Verdia and his talented staff and board at their welcome reception and throughout our visit.

NEH has awarded nearly $40 million to Alaska over the decades, including a grant to the Anchorage Museum for a forthcoming documentary on the state by Ric Burns. He experienced the 2018 earthquake inside the galleries, but Alaska has a peculiar effect: Hardships seem to draw people nearer, not deter them.

At the Anchorage Museum, National Endowment for the Arts Chairman Mary Anne Carter and I met with museum CEO Julie Decker and U.S. Senator Lisa Murkowski. A vocal supporter of federal funding of cultural organizations, the senator has a thorough knowledge of not only the large institutions, but also small, often overlooked ones. I also met with Congressman Don Young at the AHF offices, where he affirmed our work with Alaska Natives and veterans.

Other stops included the Alaska Native Heritage Center, with its living-history approach to education, staffed by deeply knowledgeable teenage and young adult guides; the three-room Alaska Jewish Museum, led by the ever-cheerful Rabbi Yosef Greenberg (he noted that the city’s first mayor, back in 1920, was Jewish); and the impressive University of Alaska, Anchorage, for a meeting with Chancellor Cathy Sandeen.

It was a particularly apt time for a visit to Anchorage because Ed and Cathy Rasmuson had invited major funders from across the country to the state in order to expand outside support. Their eponymous foundation is the state’s leading cultural funder. On a train ride from Anchorage to Indian in beautiful dining cars, the funders and potential grantees talked over how to best invest financial resources in a transformative manner.

That night I found myself hurriedly reworking my pending address for Commonwealth North, the state’s leading public policy forum, to incorporate the observations of the cultural leaders and educators whom we had met. There is nothing like speaking in a breakfast setting to keep a speaker focused and concise. I was fortunate in having a generous audience who well understood the value of the humanities to their communities.

We left Anchorage into a smoky sky from distant forest fires and flew over the interior to the town of Kotzebue, thirty miles above the Arctic Circle. We met with Northwest Arctic Borough School District staff who touted their innovative AHF-funded “culture camps” to help teachers fresh from the Lower 48 adjust to their isolated new environs. The dedicated administrators recommended the memoir Fifty Miles from Tomorrow by William Iġġiaġruk Hensley to give us a better sense of the land and its people. We were soon gifted the book.

We met with Marie Greene, chair of the Aqqaluk Trust, and Elizabeth “Liz” Qaulluq Cravalho, former chair of the AHF board and vice president of lands for NANA Regional Corporation, which is owned by the more than 14,300 Iñupiat shareholders or descendants. They described the unique interlocking structure of state, federal, and tribal resource organizations and how they partner on matters varying from infrastructure to health care to education. Our conversations drove home the importance of the state humanities councils for reaching communities that we frankly can’t from Washington, D.C., in an efficient manner.

Next, we journeyed northward over the frigid water with Perez-Verdia and Qaulluq Cravalho in a reliable, handmade, pine-and-plywood boat to a windy out-cropping of Iñupiat land where berries grew tight to the ground and talk was of the muskox that occasionally wandered into the fish camps.

We ate ripe berries by the handful, drank cool yellowish water that percolated up from a small, shallow manmade hole, added a few smooth gray pebbles to our parka pockets as mementos, and waded gingerly into the Arctic waters with bare feet, exiting rather quickly to the wet lip of the beach.

That night we reversed direction, flying to Nome to offload passengers and then some 1,000 miles to the southeast panhandle, where the mist-blanketed capital of Juneau with its narrow historic homes on the hillside looked down into the bay onto the tidy row of cruise ships, each of which sleeps more people than reside in Kotzebue and our next stop combined. We were heading to Hoonah, to be among the Tlingit.

Traveling from Juneau in a light rain via a sturdy two-story catamaran, we made our way for seventy nautical miles past Shelter Island and across Icy Strait to the hillside fishing village of Hoonah, originally Xunniyaa, which in Tlingit means “protected from the North Wind.” It had a welcoming vibe. It looked to be the ideal place to write, paint, read, dream, fish, and take aimless nighttime strolls—but the casual, recurrent warnings about bears brought back reality.

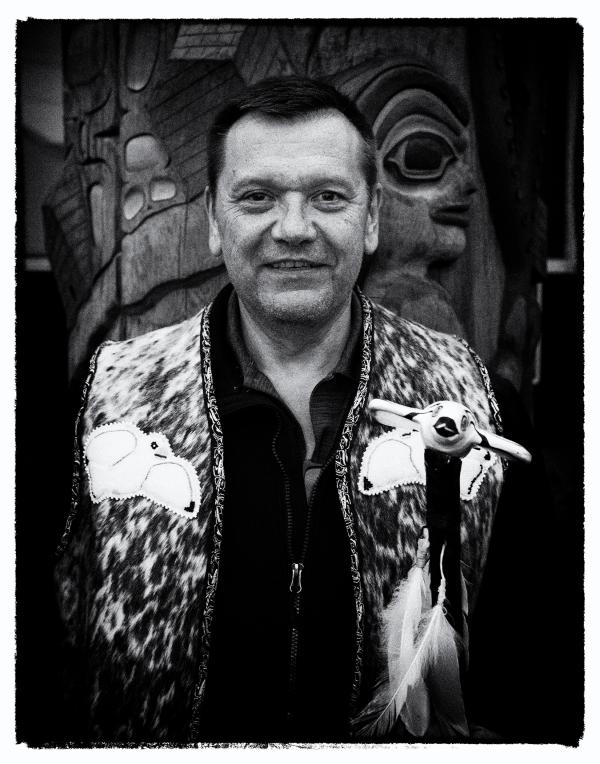

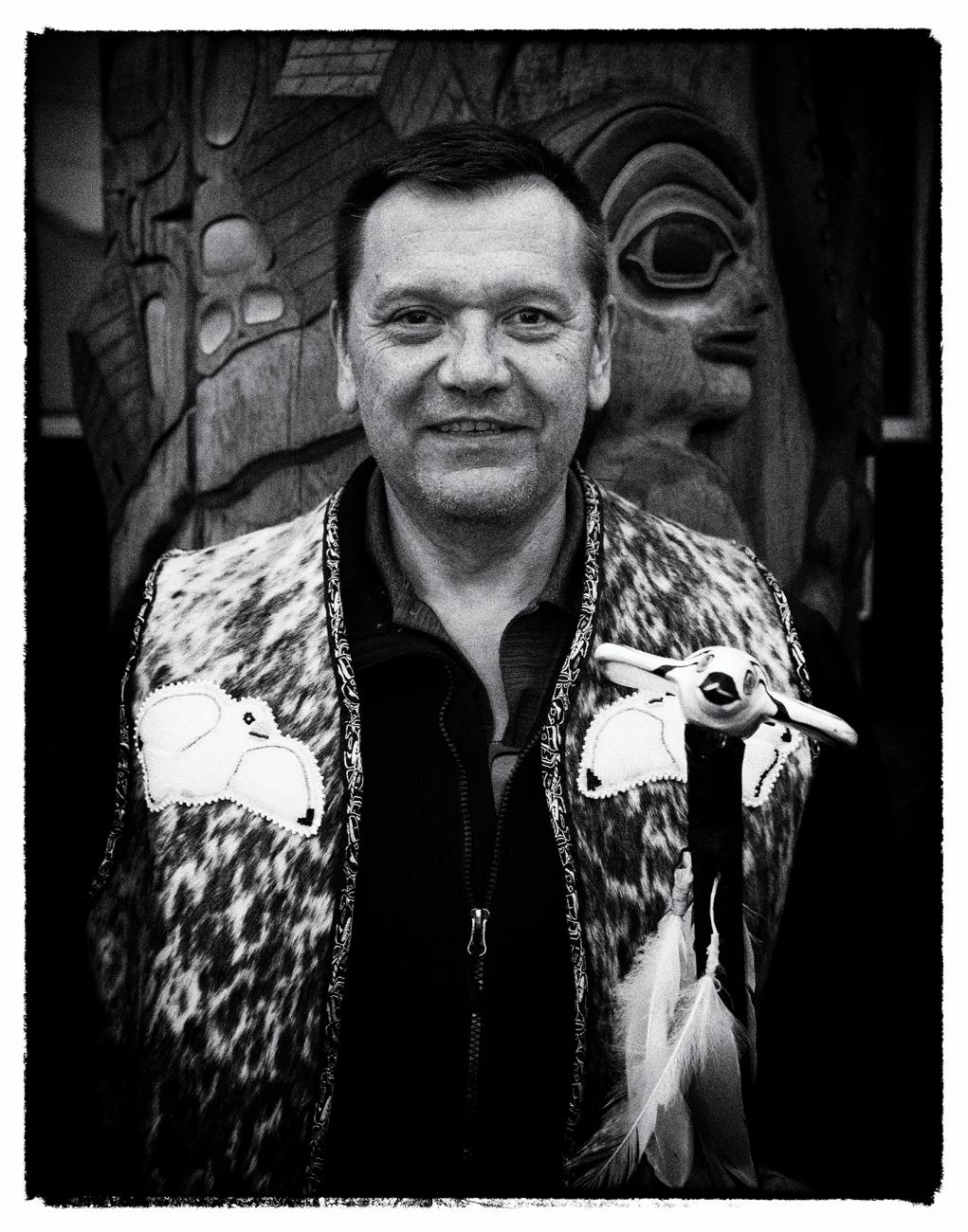

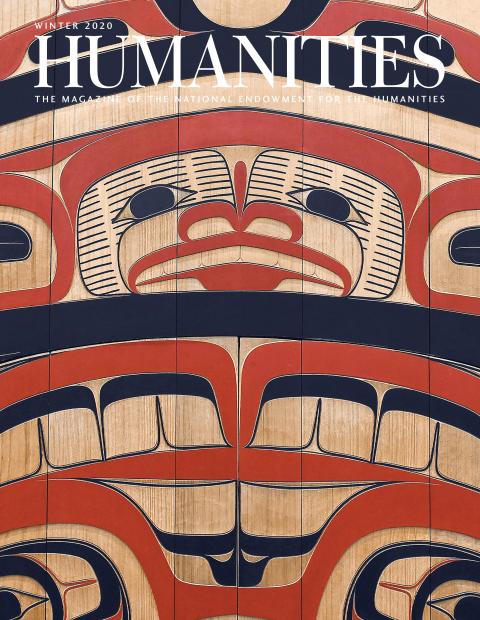

We were there at the invitation of Tlingit tribe member Robert Starbard, a Raven of the T’akdeintaan clan (Seagull), the tribal administrator of the Hoonah Indian Association, which is the federally recognized tribe of Hoonah. Starbard serves as an unofficial one-person tourism bureau for the region. A totem was being raised beside the town center. But first the local government had to vote to remove a long-overlooked ordinance that banned such an organized gathering of Alaska Natives within the town limits. When humanists speak of near and far history, they mean such moments.

We followed the story of how the Tlingit were expelled from Glacier Bay by the Little Ice Age in the 1700s and again when their ancestral land became a national monument in 1925 and a national park in 1980. The story was delivered largely in English because so many had lost their mother tongue. The totem—carved by Gordon Greenwald, an Eagle of the Chookaneidí clan (Brown Bear)—recited the prehistory in wood.

The elders turned to one another often and said a poetic word that rose with a final eesh sound. It was not a chant, but chant-like. A kind bidding. The loose audience of teens and parents returned the word to them. Later, I asked what they were saying with such reverence.

Gunalchéesh. Thank you.

Gunalchéesh. Thank you.

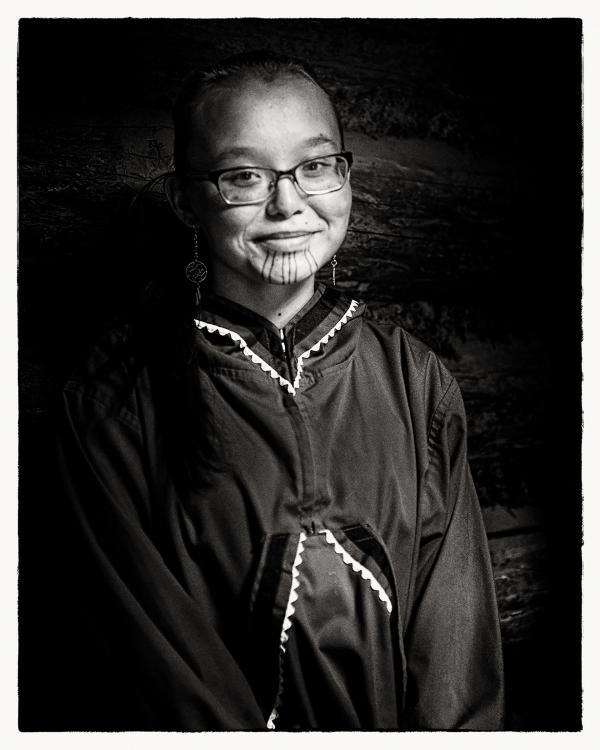

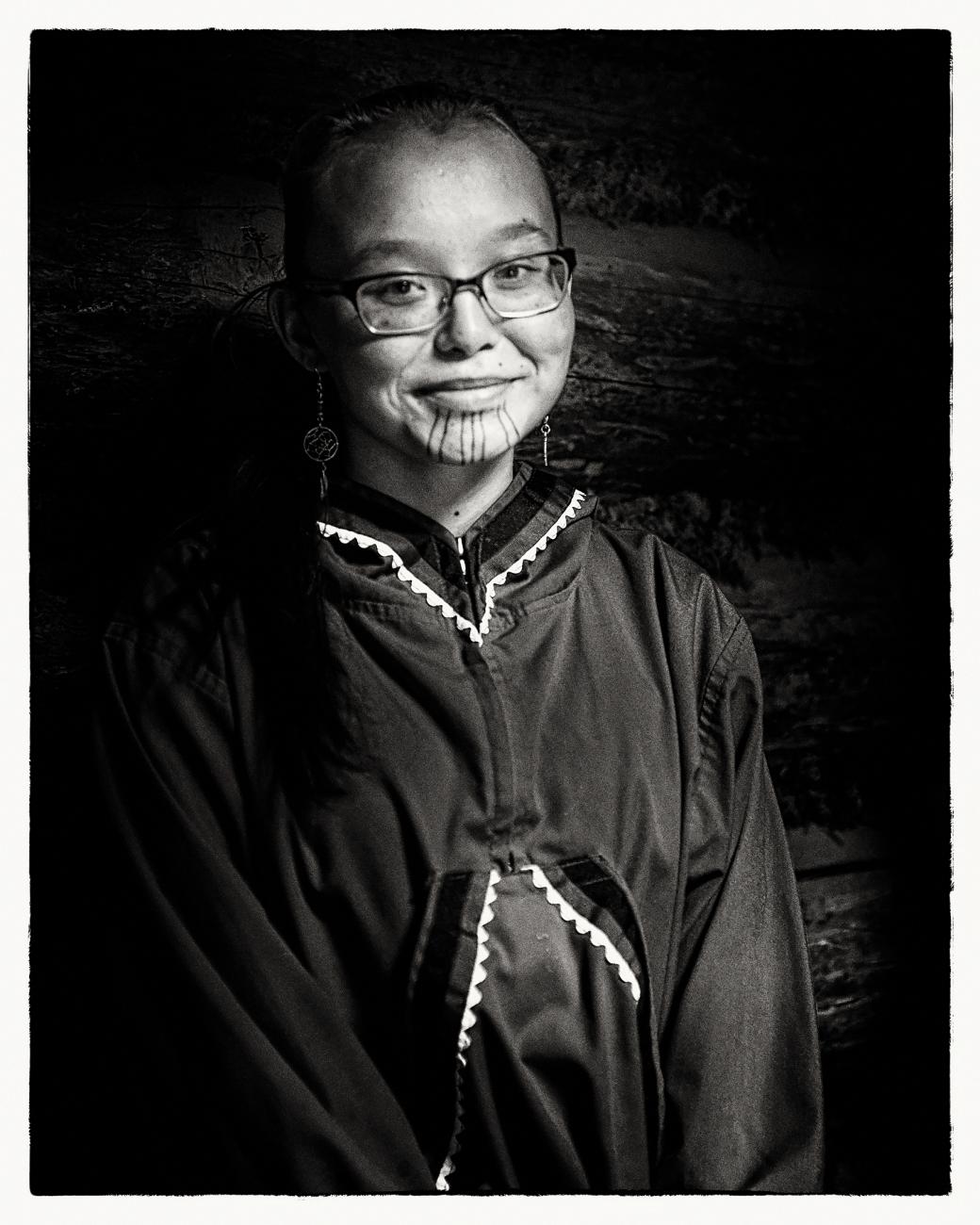

The hope for the Tlingit language is not the elders, the faithful keepers of the tribal traditions. Nor is it Starbard’s post-World War II generation. The hope rests with the energetic young in their red vests and regalia who now are taught their native language and dances and drumming at the island’s elementary and middle school.

Since 1986, NEH awarded hundreds of thousands of dollars to Sealaska Heritage Institute in Juneau for the purpose of preserving and cataloging this very language. For Tlingits and scholars alike, the archive is foundational. Gazing upon the magnificent totem beside the master carver, I felt anew the incredible privilege of witnessing the lasting value of our federal agency’s investment.

Hoonah had built a massive dock for cruise ships and was fast completing a second one. At full capacity, upward of ten thousand tourists may visit daily, seeking entertainment varying from the hillside zip line to whale watching to fine dining and shopping at the repurposed cannery. With limited housing and fewer than nine hundred residents, the town will need to stretch resources to support these guests without compromising its cultural authenticity. If the Tlingit leaders can find sufficient funding, they plan to create a museum and educational center to anchor their story in place. NEH has supported such efforts across the nation.

The morning after the totem raising, we reboarded the crowded catamaran and made our way, accompanied sporadically by whales, to Bartlett Cove, site of the National Park Service (NPS) headquarters in Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve.

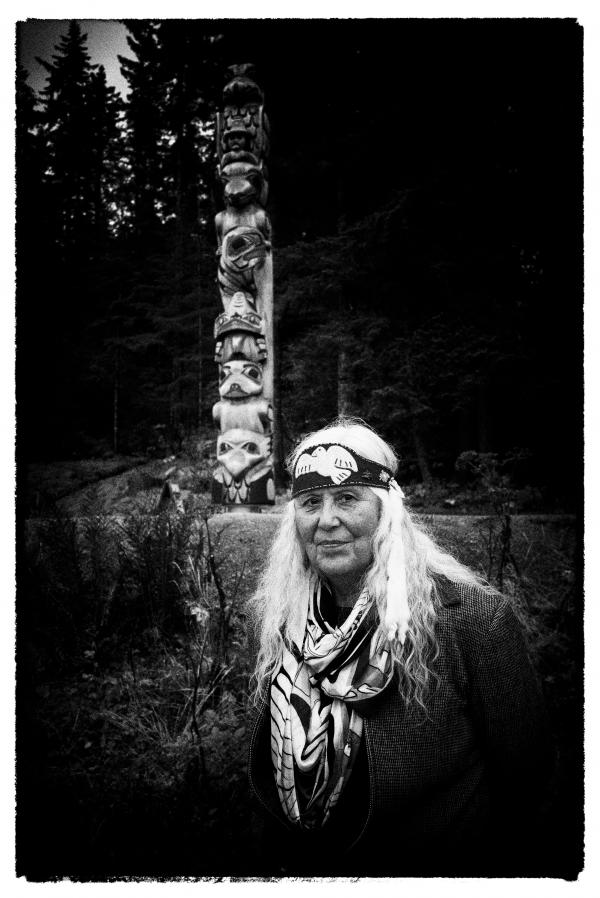

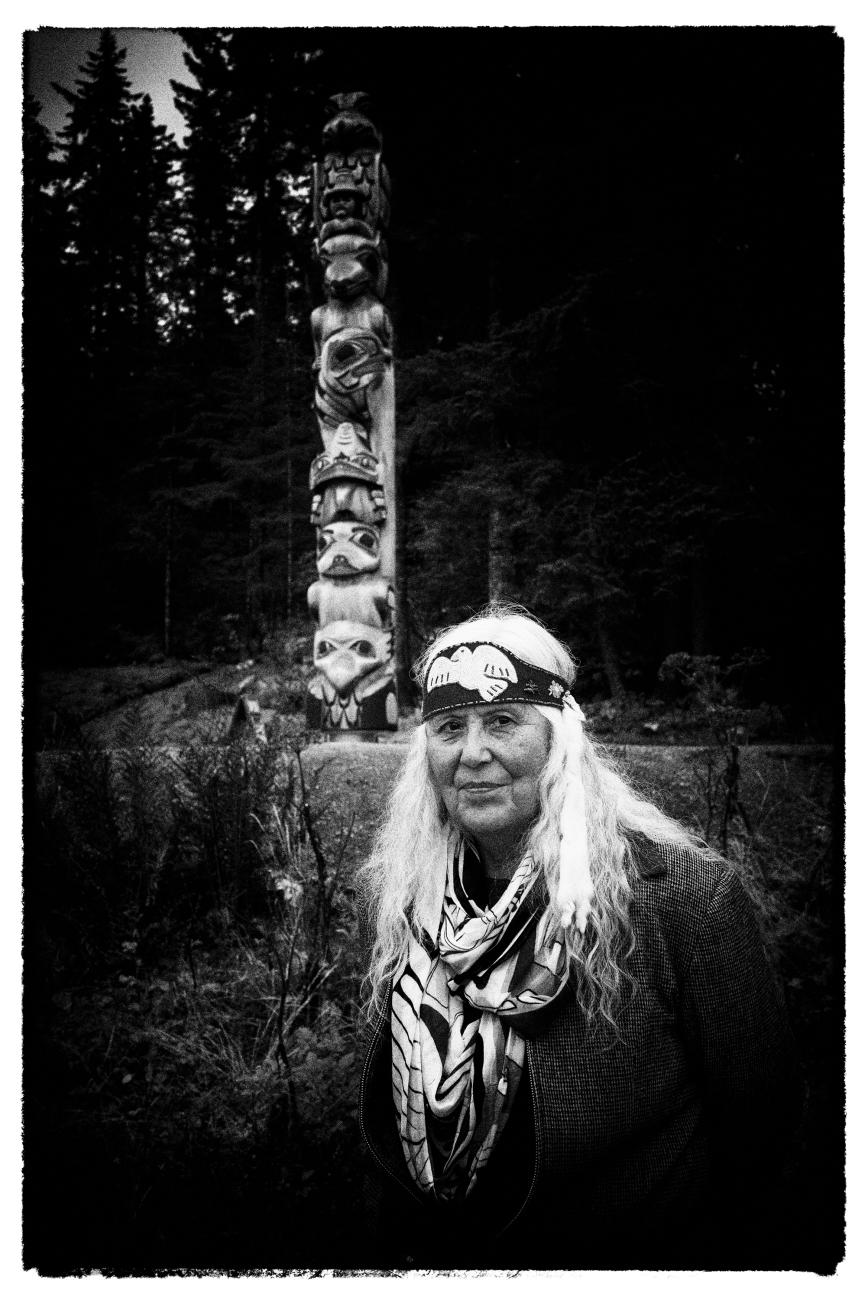

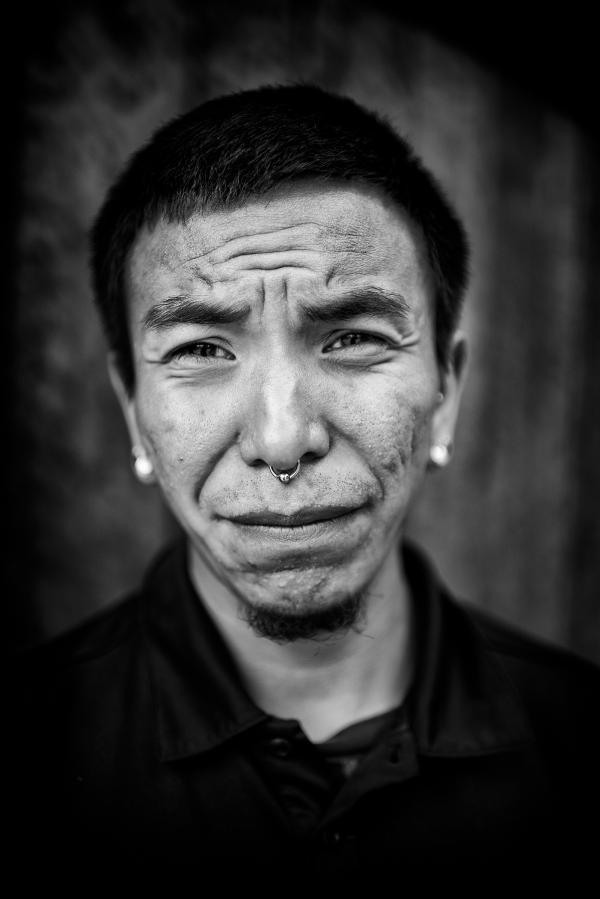

We had the rare honor of joining Tlingit families for “Journey to Homeland,” a ceremonial rite held inside Xúnaa Shuká Hít, the new Huna Tribal House dedicated in 2016. As the NPS educational website explains, it is the first permanent Tlingit house built on their ancestral land since the Little Ice Age. My NEH colleague Vincent Ricardel’s photographs narrate the peace and pleasure of the occasion that brought together not only the four original clans of Glacier Bay but other clans who live in Hoonah today, just as they had united in the construction of the 2,500-square-foot cedar structure in partnership with NPS.

In a few short years, the tribal house has already had the desired effect of establishing better relationships among the tribal members, park visitors, and NPS staff. In addition to the Eagle and Raven totems by the clan house, the Healing Pole, erected in 2018 near the dock, testifies to this positive movement.

“We searched for our mislaid culture in shelved boxes of pilot bread. / Sailor Boy, Tang, Libby’s corned beef—traditional foods / of our colonized cupboard.” A few lines from the poem “Brand Names” by Ernestine Hayes, the 2017–2018 Alaska State Writer Laureate, who is Tlingit. A journalist and creative writing professor, she won the 2007 American Book Award for Blonde Indian: An Alaska Native Memoir. Having returned to Juneau from Glacier Bay, we joined Hayes and other cultural leaders for lunch to discuss the state and the importance of its cultural heritage and how to balance it with tourism. The massive cruise ships within sight in the harbor underscored our discussion.

In addition to a healthy sprinkling of bookstores and artsy shops, the Juneau downtown boasts the aforementioned Sealaska (led by Tlingit tribal member Rosita Worl) and the Alaska State Library, Archives, and Museum, both NEH grantees and vital resources for the region. Because of our 2018 Challenge Grant of $750,000, the capital city is deep into the planning stage of the new Juneau Arts & Culture Center (the “New JACC”), a gathering place for the performing arts and humanities discussions and other educational programming. Taking a tour with New JACC board chair and former mayor Bruce Botelho and center director Nancy DeCherney, one could not help but share in their enthusiasm for this public-private cultural venture and future economic engine.

On our last full day, Starbard drove us a dozen miles outside of Juneau to Auke Bay, where we followed the well-worn footpath to the slowly retreating Mendenhall Glacier and the roaring waterfall near its base. He pointed matter-of-factly to the craggy, bare mountainside that, in his childhood, was still covered in ice. Science explains such environmental changes; the humanities, its human impact in ways large and small.

I took in his measured words and the hurried trip itself. In my mind, I replayed my Anchorage speech. I had explained to the audience that I came before them in solidarity as a native of a rural state and as a fellow citizen who believes that the economic prosperity of our great nation is inseparable from having an informed populace and a healthy culture.

Alaska’s unique cultural assets—from educational museums to sports fishing and hunting to hiking in Denali and Glacier Bay National Parks—are an unequalled strength. A continually renewing strength.

When well supported by the community and government and civic leaders, culture is a stable and dynamic and irreplaceable economic engine that enhances the lives of citizens, even as it enriches them financially.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the arts and culture sector is a $730 billion industry, which represents 4.2 percent of the nation’s GDP—a larger share of the economy than transportation and agriculture. More than 11,000 people are employed in Alaska’s cultural industry, which adds $1.4 billion to the state’s economy.

Culture is big business. Culture is good business. The creative economy is not only the future; it is the present, and it is in many ways the ongoing historic past.

The question that I put to the Commonwealth North audience—that can only be answered by Alaskans—is: What is being done to nurture the state’s cultural sector, to grow it, to capitalize on it, to promote it far and wide? Are you claiming it? And, if so, how and to what extent? Are you looking to Alaskan Native culture as foundational to the state’s culture—not merely your past but your future, too? What are you doing to integrate the cultural sector into the education and lives of the young people who will take over running this state, if they can be retained in their early adulthood years?

Whatever answers may come from such questions—and from better questions asked by more informed interlocutors—I know that NEH and AHF and our partners will play a vital role in framing and funding the best long-term solutions. I was honored to meet so many of the very people who will lead these efforts.

At the northwestern frontier of our continent, I found the same values as in my own native South: pride of place, a commitment to community, a love of language, and a vibrant urge to not merely “be” but to “belong” forever and always.

Gunalchéesh.