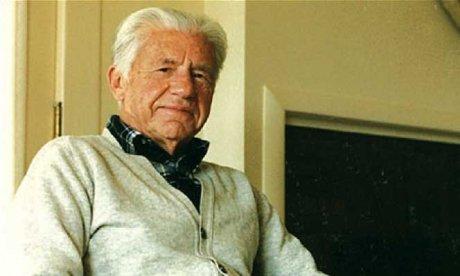

M. H. Abrams

National Humanities Medal

2013

M. H. Abrams

Courtesy M. H. Abrams

M. H. Abrams

Courtesy M. H. Abrams

For more than five decades, English majors have lugged The Norton Anthology of English Literatureacross campus, necks and backpack straps straining under the weight of volume one or two. The onion skin pages tear if turned too quickly, but thinness is a necessity when a single volume runs close to three thousand pages.

In late 1958, the president of W. W. Norton approached M. H. Abrams, a professor at Cornell University, and asked if he’d be interested in developing an anthology of English literature. Abrams agreed, thinking he would spend one summer selecting the texts and be done. Instead, it took four years. The goal of the anthology, which first appeared in 1962, was simple: provide teachers and students with the tools to explore the breadth and variety of English literature without having to constantly run to the library or juggle multiple books. Abrams also wanted to make the volume portable, so it could be read, as the introduction says, “in the student’s room, in a coffee lounge, on a bus, or under a tree.”

“We expected to sell some thousands of copies,” he told the Cornell Chronicle in 1999. “What happened was inconceivable. It took off and sold all over the world. We tried to represent the greatest of English literary works in two volumes. And over the years, the bigger it’s gotten, the better it’s sold.” The anthology is now in its ninth edition, and Abrams has passed the general editorship duties to Stephen Greenblatt.

The man who would help generations of English majors romp with Chaucer, puzzle through John Donne, and laugh with Oscar Wilde, spoke Yiddish as his first language. Born in 1912, Meyer Howard Abrams—”Mike” to his friends—grew up in Long Branch, New Jersey, the son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. As a young boy, he found a second home in the library, constantly checking out books, devouring them, and then heading back for more.

In 1930, at the beginning of the Great Depression, he headed to Harvard, where he chose English as his major and thought about becoming a scholar. “There weren’t jobs in any other profession,” he told the Cornell Alumni Magazine, “so I thought I might as well enjoy starving, instead of starving while doing something I didn’t enjoy.” His senior thesis became his first book, Milk of Paradise: The Effect of Opium Visions on DeQuincey, Crabbe, Francis Thompson, and Coleridge (1934). After graduation, he traded Cambridge, Massachusetts, for Cambridge University, where he studied for a year on a Henry Fellowship. Harvard called again, and he returned to Massachusetts, completing a PhD in English literature in 1940.

When the United States entered World War II, Abrams put aside Romantic poets for research in phonetics and philology at Harvard’s top-secret Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory. There he worked on a project to develop a phonetic alphabet for use by military forces that could cut through the noise and clamor of the battlefield. In between tests of communications equipment, he took note of Ruth Claire Gaynes, who also worked at the lab. She became his wife of sixty-two years. After the war, Abrams joined the English department at Cornell University, where he would teach for more than sixty-seven years. His students have included Thomas Pynchon, E. D. Hirsch, and Harold Bloom.

In 1953, Abrams published The Mirror and Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition, which surveys the intellectual underpinnings of Romantic literary theory and explores the expanding role that emotion and personality played in poetry. Abrams argues that before the Romantic era, what mattered most about a piece of art was how it reflected the world in which it was produced. The Romantics—Coleridge, Wordsworth, Byron, Shelley, Yeats—shifted the focus of art to self-expression, viewing and writing about the world as a series of metaphors. In 1999, the Modern Library ranked The Mirror and the Lamp twenty-fifth among the “100 Best Nonfiction Books Written in English during the 20th Century.”

Next came A Glossary of Literary Terms (1957), which offered both definition and context for students wading into literary study. Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature(1973) explored the contours of the era and demonstrated the role that theology played in the secular imagination. His volumes of essays include The Correspondent Breeze: Essays on English Romanticism(1984) and Doing Things with Texts: Essays in Criticism and Critical Theory (1989). In 2012, at the age of one hundred, he published The Fourth Dimension of a Poem and Other Essays.

Abrams’s scholarship has been recognized by numerous awards, including fellowships from the Guggenheim, Ford, and Rockefeller foundations. In 1984, he received the Award in Humanistic Studies from the Academy of Arts and Sciences. The Award for Literature by the American Academy of Arts and Letters followed in 1990.

—Meredith Hindley