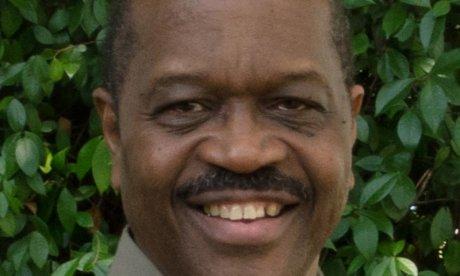

Everett L. Fly

National Humanities Medal

2014

Everett L. Fly

—Rosalinda Fly

Everett L. Fly

—Rosalinda Fly

WHITE HOUSE CITATION

Everett L. Fly, for preserving the integrity of African-American places and landmarks. A landscape architect, Mr. Fly has worked tirelessly to win historical recognition for Eatonville, Florida, Nicodemus, Kansas, and other sites central to African-American history, preserving an important part of our broader American heritage.

At his first meeting as a board member for what was then called the Texas Council for the Humanities, Everett Fly was asked, “Why is there an architect on the humanities council board?”

The newcomer had an answer. “For me, landscape architecture’s connection to the humanities is the culture of the people represented or expressed in what we design,” he said.

Fly’s ideas have influenced not only the humanities council (he served for 11 years) but also his profession. For nearly four decades, he has been using architecture to find and preserve crucial places and stories of American culture.

His fascination with history took shape when he was growing up in San Antonio, Texas, where he still lives with his wife, Rosalinda. The city is, of course, home of the Alamo, the Majestic Theatre, Spanish missions, and much more. It boasts “a tremendous mix of cultures here,” he explains, “people from Spain, Mexico, Native Americans, German immigrants, Czech, black, you name it.”

After studying architecture at the University of Texas at Austin, Fly became the first African-American graduate of the master’s program in landscape architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. When he noticed that his classes rarely mentioned the buildings and places significant to African-American culture and heritage, he commenced a research project he calls “Black Settlements in America,” a career-long study of the origin and evolution of historic black settlements.

“When I started working with the history of these black settlements and towns, it was really a quest to answer questions for myself,” Fly says. Or, as he told Humanities Texas in 2013: “I was always interested in how people related to buildings, not just physical styles of buildings or building materials, not just the abstract aspects of architecture and landscape architecture. I wanted to know how people related to them. Why did people settle in a place, or why did they build a building a certain way?”

Ever since then, Fly has been saving and unearthing historically significant but forgotten or unrecognized Native- and African-American settlements, which he numbers at over 1,200: Hobson City, Alabama; Idlewild, Michigan; Nicodemus, Kansas, and many more. Fly has been summoned to towns across the land. Using old maps and records from archives as well as his experienced eye for discerning artifacts like fence lines, he reveals history that has gone undocumented. Fly’s work might help properties get listed as historically significant, or result in them becoming tourist destinations and educational opportunities. For example, his work protected Eatonville, Florida (the oldest incorporated African-American municipality in America, whose history stretches back to the late 19th century, and childhood home of writer Zora Neale Hurston) from a road-widening project.

“It’s hard to travel in any state and not find some significant place or building site where there’s notbeen some contributions of African Americans,” Fly says. “Black craftspeople over the centuries have worked on everything from the White House to naval shipyards to the state capitol in Austin,” he says. Fly recently salvaged hand-forged nails from a decades-old building crafted by African Americans, which “represented the hand trades and crafts of the black folk that built it,” he says.

To Fly, preservation is about more than the past. “When different groups of people understand how their ancestors contributed and worked together in the built environment, they realize that no one person can do everything—make the bricks, the glass, the nails,” he says. “It takes a whole team of folks to put it together.”

Just as Fly has helped change the humanities’ view of architecture, humanities-infused work has been part of a broader transformation in his profession. Today architects increasingly go beyond aesthetic considerations to ask how buildings and places affect the people who use them.

“I was trained studying the great masters of architecture and I refer to some of those masters every day,” Fly acknowledges. “But as societies and culture evolve, the perspectives change, the values change, the mix of the folks involved changes. Architecture is one of the professions that need to adjust along with those, as we need to address everything from environmental issues to social issues.”

Fly’s seemingly obscure historical work is especially relevant in this year of deadly cultural conflict in places like Ferguson and Charleston. “If we want our American cities to be healthy and sustain them in the future,” he says, “we have to find ways to value not just new office buildings and developers that have the most money and political clout. You find collective history in places where everyday people worked and made contributions that are just as valuable as a big businessperson or landowner. If you can find those connections to their history, people can have a closer relationship to their community.”