Humanities on Campus

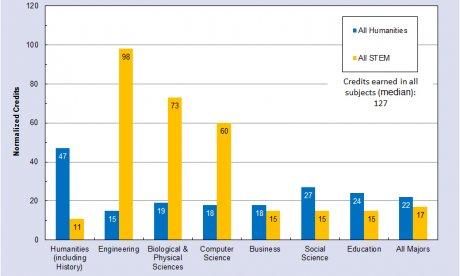

Median number of college credits earned by 2008 graduates in humanities and STEM subjects, by student major, from the Humanities Indicators

Courtesy of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences' Humanities Indicators

Median number of college credits earned by 2008 graduates in humanities and STEM subjects, by student major, from the Humanities Indicators

Courtesy of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences' Humanities Indicators

A typical college graduate earned 17 percent of his or her credits toward graduation in the humanities, compared to acquiring only 13 percent of credits in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math, according an analysis of college transcript data published at the Humanities Indicators project.

This is a surprising finding in light of the number of students majoring in the two subject areas. Roughly 12 percent of students major in the humanities, compared with 15 percent in the sciences.

The data, drawn from the Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study on college students who graduated in 2008, show that by and large students majoring in STEM fields tend to avoid humanities courses, while non-STEM majors largely eschew classes in science, technology, engineering and math. STEM majors earn fewer credits in the humanities than do students majoring in other areas, the study indicated, but humanities majors tended to earn fewer STEM credits than STEM majors earned humanities credits.

The lack of diversity on student transcripts signals a failure in higher education to “make clear why breadth in general education is important and how courses outside a student’s areas of primary interest can be valuable,” comments John G. Hildebrand, Regents Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Arizona, in a Humanities Indicators forum that looks at which students take humanities courses in college. “American colleges and universities produce well-trained and skilled graduates in fields as diverse as accounting, chemistry, instrumental music, molecular biology, premedical studies, psychology and political science,” he writes. “But do we do as well in educating our students to be good citizens who will live rewarding and enriching lives?”

Norman M. Bradburn, professor emeritus and former provost at the University of Chicago and co-principal investigator of the Humanities Indicators project, points out that universities’ academic structures can limit students’ opportunities to take humanities classes. “At many large universities, which the majority of students attend, students apply to a college within the university (such as the college of business, college of education, etc.), which has its own curriculum and distribution requirements. While it may be possible to take courses in the other colleges, the initial choice of a college within the university effectively determines the number of humanities courses available to a student,” he says. “ Although there is some ability to change colleges within large universities, the initial choice of college restricts the humanities courses that one can take to a much greater extent than in a liberal arts college, where the selection of a major and there is greater freedom to explore different fields.”

See additional data and commentary on STEM and the humanities at the Humanities Indicators Academy Data Forum “Enclosed in a College Major? Variations in Course-taking among the Fields.”

The Humanities Indicators, an effort by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences to compile, analyze and publish comprehensive trend data about the humanities, covering primary and secondary education in the humanities, undergraduate and graduate education, the humanities workforce, humanities funding and research, and the humanities in American life, is supported by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.