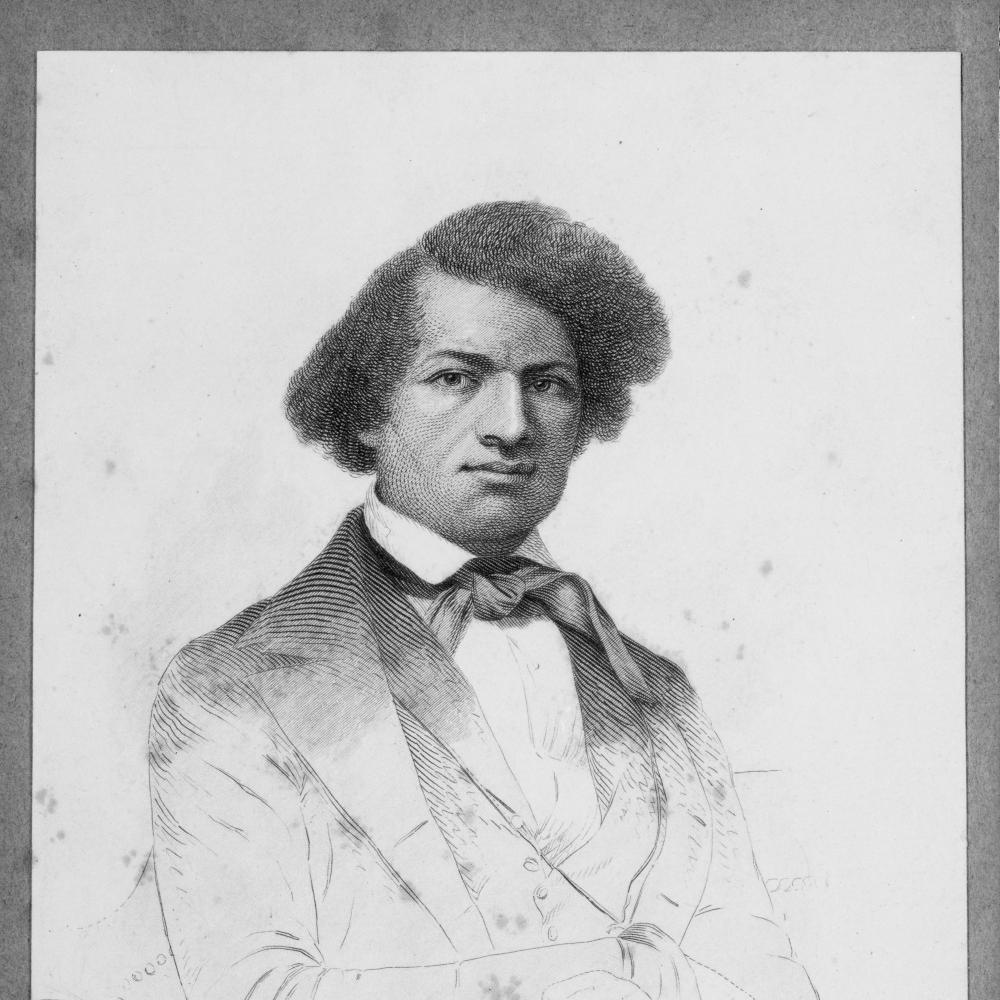

For this edition of IQ, Robert S. Levine introduces us to Frederick Douglass, whose complexities and writings are covered in his book The Lives of Frederick Douglass (Harvard University Press, 2016). Levine, a professor of English at the University of Maryland, says Douglass's life was one of constant revision and change. Levine spent eight years dissecting Douglass’s letters, newspaper articles, speeches, and three autobiographies. In 2012 he received an NEH research fellowship to support this work.

Why do you study Frederick Douglass?

I’ve had a long fascination with nineteenth-century American literature and culture, and Douglass spanned that period and addressed the big issues of the time: slavery, race, women’s rights, and immigration. He’s also a great prose stylist. When you study Douglass, you read truly superb writing.

Most people know the story of Douglass’s daring escape from slavery and his work with William Lloyd Garrison. What else do you wish people knew?

Douglass published his most famous autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, in 1845; Garrison was his publisher. But Douglass lived another 50 years. Around 1850 he broke from Garrison. He published two additional autobiographies—My Bondage and My Freedom and Life and Times—and a novella, The Heroic Slave. He collaborated with John Brown, met with Lincoln three times, toured Egypt, attended numerous women’s rights conventions, spoke out against the rise of lynching, and was a political friend of Ulysses Grant. Near the end of his life, as U.S. consul to Haiti, he supported Haiti’s decision to deny the U.S. government’s request to set up a naval station there.

Douglass chose his surname. What does it signify?

Douglass was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. When he escaped, he changed his name to Frederick Douglass, taking the surname of one of the rebellious heroes of Sir Walter Scott’s 1810 narrative poem The Lady of the Lake. Douglass clearly saw himself as being in the romantic tradition of Scott’s James Douglas, a character who is imprisoned as an enemy of the Scottish king but is eventually pardoned and celebrated.

How did Douglass and Garrison become frenemies?

Garrison was the publisher and editor of The Liberator, which became the most popular antislavery newspaper in America. When Douglass decided to start his own newspaper in 1847, Garrison was furious, and by the early 1850s he was lashing out at Douglass, accusing him in The Liberator of having an affair with his British friend Julia Griffiths, who was the managing editor of Douglass’s newspaper. After the embarrassed Griffiths returned to England, Douglass took a measure of revenge by presenting Garrison as a paternalistic racist in My Bondage and My Freedom.

Who were his trusted friends?

The private Douglass remains elusive, though biographers are working to uncover friendships that never became fully public. One such friendship was with Ottilie Assing, a German woman who translated My Bondage and My Freedom into German and then journeyed from Germany to Rochester to meet with Douglass in 1856. They remained close friends and were perhaps lovers, as Assing regularly accompanied Douglass on his speaking tours. Douglass’s first wife, Anna Murray Douglass, died in 1882. In 1884, the same year that Douglass married his white secretary, Helen Pitts, Assing killed herself. Douglass does not comment on his relationship with Assing in his final autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass.

You call Douglass an Anglophile. How so?

Douglass loved British literature, especially Shakespeare and Charles Dickens. During the 1850s, he serialized Bleak House in his newspaper. A decade earlier, after the publication of the 1845 Narrative, Douglass went abroad to avoid fugitive slave hunters. He was embraced by English abolitionists and enjoyed giving lectures in major British cities. But he perhaps enjoyed even more the conversations and social occasions with the British antislavery crowd.

Did his time with the Irish nationalists in the 1840s change him?

Douglass was resistant to the idea at first, but, during his months in Ireland in the mid 1840s, he came to see that the Irish working poor and U.S. slaves had a lot in common. Read Colum McCann’s novel TransAtlantic for an interesting take on Douglass’s time in Ireland.

The Heroic Slave draws on the real life of Madison Washington. Why was Washington’s story so important to Douglass?

Madison Washington led the slave revolt on the American slaver Creole in 1841. The slaves killed a white officer and gained their freedom in the British Bahamas. Initially, Douglass was a moral suasionist like Garrison, convinced that violence was bad for the antislavery cause. But after breaking from Garrison, Douglass came to believe that the violence of slavery merited a violent response, and Washington became one of his heroes and the subject of a number of his lectures. In his novella, Douglass presents Washington as an orator who sounds a lot like Douglass; Washington is arguably a fantasy version of Douglass as the heroic black who leads his people to freedom.

John Brown was a “constant thorn in my side,” according to Douglass. In what ways was Brown prickly?

Brown was prickly because he was so principled. Principled people tend not to be pragmatic, as Douglass came to realize when Brown, during a secret meeting in a small town in Pennsylvania, asked him to join the raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Douglass declined, but as he makes clear in his speeches and in his chapter on Brown in Life and Times, there were few white men in America that Douglass admired more than Brown.

Why didn’t Douglass support Lincoln’s presidential candidacy in 1860 or 1864?

Douglass wanted a radical abolitionist for the presidency in 1860, and in 1864 he initially supported John C. Frémont because he thought Lincoln wasn’t completely committed to the antislavery cause. During the opening years of the Civil War, Douglass was so frustrated by Lincoln’s hesitancy to argue for antislavery that he printed an article in his Douglass’ Monthly declaring that there were no essential difference between Lincoln and Jefferson Davis. By the time of the Second Inaugural, Douglass was very pleased that Lincoln was president.

Your favorite Frederick Douglass story? Best and worst traits?

I am fascinated by the various stories of Douglass’s seeming reconciliation with his former master, Thomas Auld, in 1877. According to Douglass’s account in Life and Times, theirs was a tearful reconciliation on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Douglass intensifies his account by stating that the meeting occurred shortly before Auld’s death. But Auld lived for another few years. On close examination of this and other of Douglass’s accounts of the apparent reconciliation, Douglass seems intent on displaying his worldly success to his former master. Douglass could be vain at times. But this scene also conveys Douglass’s conviction that blacks had just as much right to call the South their home as whites. Among Douglass’s many strengths was a racial pride and concern for the larger black community.

In 1848, Douglass stood for women’s rights at Seneca Falls, and in 1888, declared, “I am a radical woman suffrage man.” What kept him true to women’s rights even when the suffragists treated him abominably?

In defense of the suffragists, they were upset with Douglass’s support for the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave black men (and not white women) the right to vote. Susan B. Anthony and others insisted that Douglass should withhold his support for the amendment until it included women.

In defense of Douglass, he believed that if “men” had the right to vote, then that should be true for men of all colors. But he never for an instant stopped arguing for women’s suffrage. He believed in human equality and had a nearly 50-year commitment to women’s rights. He died in 1895 shortly after giving a speech at a women’s rights convention.

Why do you say Douglass had “faith in writing itself.”

Douglass was a man of words. In James McBride’s novel, The Good Lord Bird, the narrator mocks Douglass for refusing to join Brown at Harpers Ferry, decrying how he regularly chose words over action. But for Douglass, writing was action, as he saw early on in his career when his Narrative galvanized abolitionists. This orator and activist believed that writing could change the world.