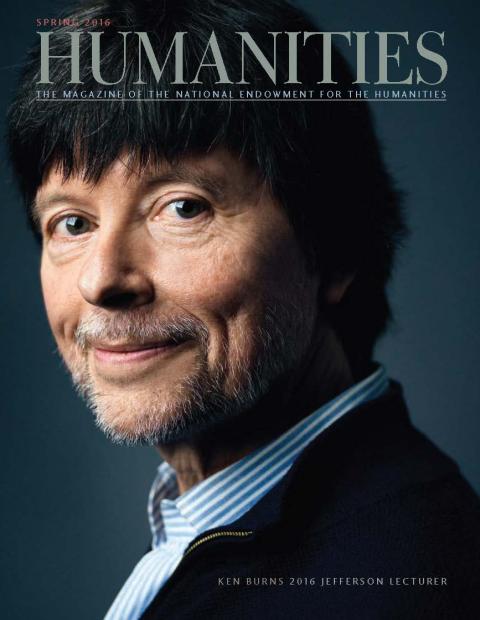

If I were to make a film about Ken Burns, no doubt the first shot would be of Walpole, the churchy postcard of a New England town in which he and his film company reside. Next, I’d want a close-up of the cup, inside a meeting room at Florentine Films, filled with perfectly sharpened No. 2 Ticonderoga pencils, which are Ken Burns’s favorite brand of pencils. After that I might try a shot panning across the back of editor Paul Barnes working at a bank of monitors. To his right is a box of Kleenex for people, like me, who forgot to check their feelings at the door before watching clips of The Vietnam War, Burns’s next epic, which was supported by a production grant from NEH.

I was accompanying NEH Chairman William D. Adams for his interview with Burns, included in this issue. And while the chairman asked the man himself about his life, career, and what gives his work its heroic sense of mission, I tried to learn what I could.

During a stop on my way north, Larry Hott, an old friend of Burns’s from their Hampshire College days, and a well-known director in his own right (Through Deaf Eyes, Rising Voices), recalled for me the time he worked on Burns’s senior thesis, Working in Rural New England, a 27-minute film made for Old Sturbridge Village in western Massachusetts.

A cinéma vérité portrait of farm life at the dawn of the industrial era, the film followed the village’s historic reenactors as they went about plowing, blacksmithing, weaving, and so on. Hott gushed over a scene around the 7-minute mark in which a farmhand gently takes hold of a sheep, its pink nostrils aquiver, and slowly cuts away its fluffy wool, using old-fashioned, hand-forged sheers. Hott compared it to Michelangelo’s Pietà, the famous sculpture of Christ’s body held in the lap of his mother, Mary—such was the intensity of the moment and the care that went into shooting the scene, in what was merely a student project. A selected filmography in this issue suggests where such care led—to dozens of excellent films.

Also in this issue, we learn from contributor Danny Heitman about the life and work of poet Marianne Moore, who cleverly managed her own image as the spinster aunt of American literature.

The great Garrison Keillor is stepping down from A Prairie Home Companion, the live variety show and public radio mainstay that he created. Writer Peter Tonguette interviewed Keillor at length to learn what’s next for him.

Danielle Allen, author of Our Declaration, a striking book that arose from her experience teaching disadvantaged adults about the American founding, writes about the important connection between a humanities education and one’s readiness to participate in our civic culture.

And Emily St. John Mandel, whose novel Station Eleven was a finalist for the National Book Award, remembers her experience as the featured author in the Great Michigan Read, which is supported by the Michigan Humanities Council. It was a long year for her, a special year, too, but also a strange year.

Last, there are two pieces of magazine business to mention. One, HUMANITIES the print title is now a quarterly. For years our online audience has been growing steadily and outpacing our print readership. This shift from six print issues per year to four will enable us to redirect resources to expand our web content. Two, as we turn the ship in this digital direction, we are conducting a reader's survey online at www.neh.gov/humanities/survey. Please take a minute to visit our website and let us know what about this magazine strikes your fancy or not.