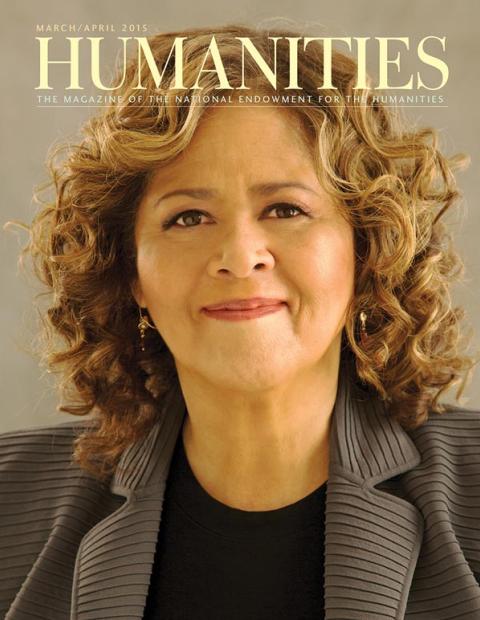

Even in an era when anyone with a computer connection can broadcast their own life story for everyone or no one to consider, Anna Deavere Smith continues to shock and dazzle audiences with her stage portraits of the humble and the great. A hybrid artist if ever there was one, she collects stories through recorded interviews and then portrays the tellers on stage, in curated displays of American character organized around pressing questions of our time.

Smith was born on September 18, 1950, in Baltimore, Maryland, the first of five children to Anna, an elementary school educator, and Deaver, a coffee merchant.

In middle school, she discovered a gift for mimicry; in college, an interest in social justice. As one of only a few African-American students at Beaver College in the 1960s, she recently told NEH Chairman William Adams, she helped form a black student group, which led to changes to the curriculum and to the hiring of the school’s first black professor.

After graduation, she drove west with four friends. Their goal, as she put it in her memoir, Talk to Me, was “to see America and to make sense, each in our own way, of what to do with all the breakage and promise that had been released through the antiwar movement, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, the beginning of the environmental movement, and the bra-burning, brief as it was, of the women’s movement.” Casting about for a line of work that would suit her, Smith called up the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco and asked if they were looking to hire a stage manager. The answer was an emphatic no, but she stayed on the phone and asked about classes for actors, which led to an audition and enrollment.

A transformative moment came early in her training, when Smith encountered Shakespeare. Like countless actors, she was afraid of the Bard, afraid of giving voice to “that thick, antiquated language that seemed totally irrelevant to the world around me.” Her teacher instructed the class to “take fourteen lines of Shakespeare and say it over and over again to see what happened.” Smith picked a speech from Richard II in which Queen Margaret bitterly laments the devastation wrought by Richard, “That foul defacer of God’s handiwork, / That excellent grand tyrant of the earth.”

Smith, who had once thought of becoming a linguist, was affected by the exercise, especially its simple, repetitive focus on saying the words. As she told The Drama Review, “I had some kind of transcendental experience. . . . For the next three years, as I trained seriously, I never had an experience like that again.”

One result was that Smith did not become a method actor, that is, an actor who uses their own personal experience and the context of the play to understand a character’s motivation. Instead, she came to view language itself as the great window onto character. And repeating the language became central to her process. On this point, she often quotes her grandfather, who told her as a little girl that “if you say a word often enough, it becomes you.”

Smith had gone out west in search of America and found herself on stage, so it is not really surprising that her next big idea for the stage came from outside of the theater. As she told the story in Talk to Me, Smith worked several odd jobs in offices and restaurants after she left the conservatory. At KLM Airlines, she worked in the complaint department, handling correspondence from dissatisfied customers.

“There was the man who was outraged about a flight with a drunken soccer team that ended with lost luggage—luggage that had his glaucoma medicine in it. Then there was the woman whose eighty-five-year-old mother had flown in from Egypt to Dulles Airport. KLM was to have provided an escort, as the mother knew nothing about Washington, had never been to the United States, and spoke no English. They failed to send the escort, and so the mother, somehow, ended up in a cab in Washington, D.C., driving around all night, with no idea of where she was and no ability to tell anyone where she needed to be.”

The stories made Smith wonder: “If I were to go around and listen listen listen to Americans, would I end up with some kind of a composite that would tell me more about America than is evidently there?”

The first of her shows to portray real-life people used twenty actors to represent twenty real New Yorkers, whom she recruited by approaching on the sidewalk and saying, “I know an actor who looks like you. If you’ll give me an hour of your time, I’ll invite you to see yourself performed.” A year later, she developed a similar project in Berkeley, California.

The basic idea might have seemed whimsical, but it had parallels in other fields. Like the new historians who were combing archives for previously neglected voices, or the Hollywood directors in search of a more personal style of filmmaking (to draw examples from the careers of Harvard president Drew Gilpin Faust and filmmaker Martin Scorsese, two other recent Jefferson Lecturers), Smith was looking to portray a greater diversity of personal experience. The next twist was for Smith herself to portray her characters in one-woman shows.

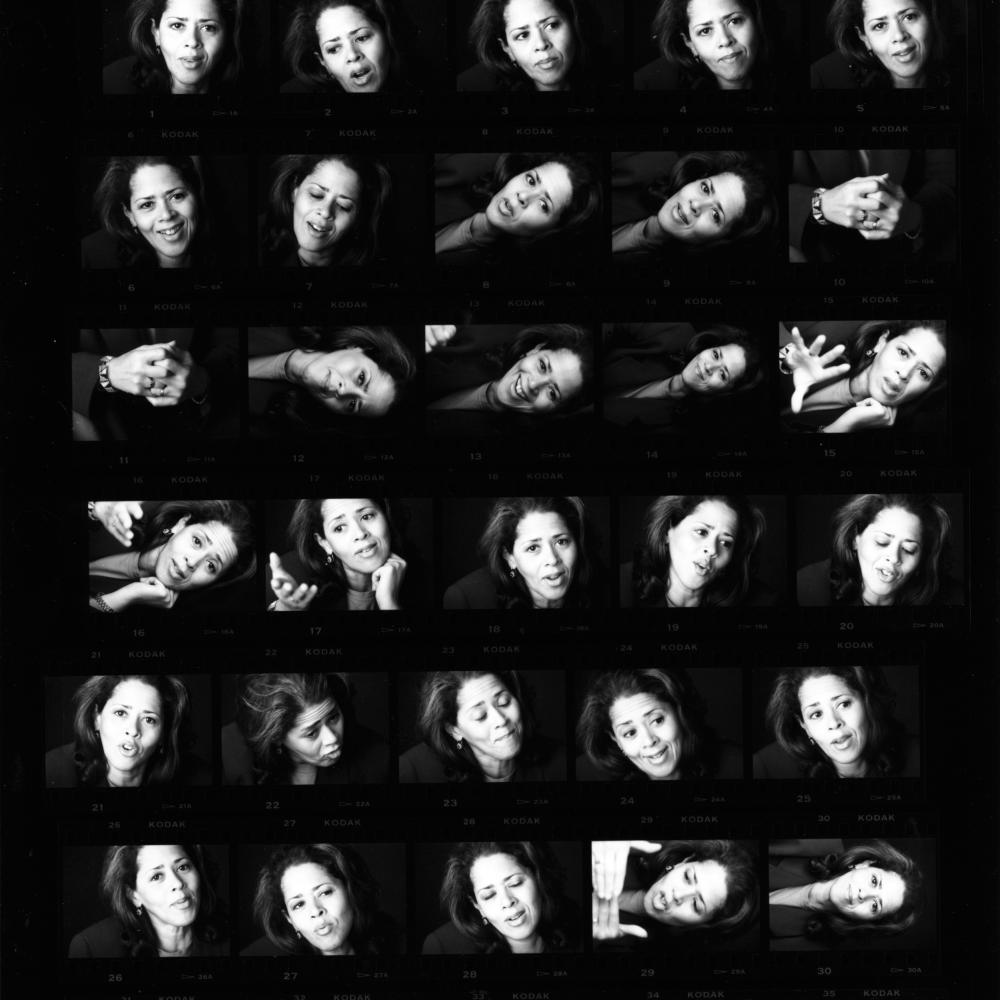

More than a political gesture or a dramatic conceit, her plan had surprising artistic implications. As she told NEH Chairman William Adams, Smith learned to approach the language of her interviewees the way she would a Shakespearean monolog, assuming that the story as told—these sentences, in this order, with these words, complete with false starts, coughs, laughter, and so on—was the truest and best way to present a character. “If they said ‘um’ . . . I don’t take the ‘um’ out.”

The title she gave to her project recalled her own journey, even as it spelled out her vaulting ambition: “On the Road: A Search for American Character.” It was the work of a lifetime, a theatrical equivalent to the Great American Novel driven by a Whitmanian urge to “contain multitudes.”

The first years have not left a long paper trail, but there were several productions. A performance based on an interview with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, a former foreign correspondent and journalist who was the first African-American student to integrate the University of Georgia, played in 1984 at the Ward Nasse Gallery in Soho.

In 1988, Smith appeared at the West Coast Woman and Theater Conference, which brought a good deal of scholarly attention. In this production, On the Road: Voices of Bay Area Women in Theater, Smith represented twenty-three living women. Writing in Theater Journal, Esther Beth Sullivan, then at the University of Washington, noted that Smith “managed to isolate gestural and vocal idiosyncrasies that characterized the speakers and personalized the significance of their statements.” The show, continued Sullivan, “progressed almost as dialog among the ‘characters.’ Various statements were juxtaposed with others that refuted them, or had an entirely different perspective.”

Although a professor herself, Smith was no apple-polisher for campus tradition. Gender Bending: On the Road, a work commissioned by various departments at Princeton University, dealt with the men-only policies of two of the school’s eating clubs. Smith’s individual portraits still delivered individual stories, but they also functioned as panels in a larger mosaic of communities in conflict.

In 1991, a seven-year-old African-American boy named Gavin Cato was killed in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, by an out-of-control car that was part of a motorcade for a prominent Hasidic rabbi. Following the accident, Yankel Rosenbaum, a Hasidic Jew from Australia who had been studying with the local Lubavitch community, was killed nearby in an act of revenge and several days of rioting ensued. Smith was invited to develop a show based on these incidents for the New Voices of Color festival, organized by George Wolfe at the Joseph Papp Public Theater.

From eight days of interviewing, Smith developed two dozen portraits to perform in Fires in the Mirror: Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and Other Identities, illuminating longstanding tensions between the black and Jewish communities and trotting out one extraordinary individual after another. Here was Al Sharpton, man of the hour, on full display; here was Rosenbaum’s brother, putting match to the fumes one moment and, in another turn on the stage, quietly recalling the moment he received the terrible news that his brother was dead.

Among the many people won over by the show was Frank Rich, chief theater critic of the New York Times, who called it “the most compelling and sophisticated view of urban racial and class conflict . . . that one could hope to encounter in a swift ninety minutes.”

Triumph followed triumph as Smith moved onto her next major project, Twilight: Los Angeles, another commissioned piece, this time on the riots that followed the acquittal of four police officers caught on videotape beating Rodney King. The cast of characters was larger than in Fires in the Mirror, as Smith stretched to portray rioters, a juror, police commissioner Daryl Gates, Reginald Denny, who was pulled from the cab of his truck and assaulted on national television, and dozens of others. Smith’s halting, bilingual portrayal of a Korean-American woman whose business had been burned down reminded one of the line from Terence that “nothing human is alien to me.”

In 1996, Smith was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, the so-called genius grant. An artist of the modern city, Smith turned her attention to Washington, D.C., drawn by the mounting antagonism between the White House and the press. Finagling a ten-minute interview with Bill Clinton, she asked him if he thought the media was treating him like a common criminal; the president spoke in reply for more than a half hour. The question became even more pointed as, months later, the Monica Lewinsky scandal broke, and Smith interviewed hundreds of Washington figures, resulting in her multi-actor play House Arrest and her memoir Talk to Me.

Having appeared in The American President, the 1995 film written by Aaron Sorkin, Smith went on to play National Security Advisor Nancy McNally on Sorkin’s television series The West Wing for six seasons. In 2006, Smith published her second book, Letters to a Young Artist, in which she comments on her own work and dispenses advice to a fictional painter. In 2009, she began appearing in a regular role on Nurse Jackie, an acclaimed Showtime series starring Edie Falco. This year she shot several scenes for an upcoming episode of the hit show Blackish.

Smith’s last major one-woman show took her interest in politics in a new direction, as she plunged into timely questions of physical health and medical care in Let Me Down Easy. She portrayed doctors, media figures, and well-known athletes in a well-paced and thoughtful stage piece that relocated the dramatic focus of our current debates back onto what Shakespeare called “the thousand natural shocks / that flesh is heir to.”

Smith is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including a 2012 National Humanities Medal, which she received from President Obama. In her latest project, Smith is visiting communities across America to interview people concerned with the school-to-prison pipeline, a phrase referring to the systematic education failures that push disadvantaged children, males especially, from trouble in school to a life behind bars. The work has taken her back to Baltimore and is creating conversations around some of the identity issues that marked her pioneering stage work.