On May 26, 1914, Teddy Roosevelt ventured to Washington, D.C., to deliver a lecture at the National Geographic Society.

Only a week before, Roosevelt had appeared in New York a jaundiced, frail version of his legendary robust self, after a seven-month trip deep into the Amazon jungle. While trying to save a canoe from being swept away by the River of Doubt, he had injured his calf. The wound became infected, and tropical fever engulfed his body. A bullet still lodged in his chest from an unsuccessful assassination attempt in 1912 further compromised his health. Roosevelt grew infirm and feverish as he deliriously repeated the opening lines of the dream poem Kubla Khan: “In Xanadu did Kubla Khan / A stately pleasure-dome decree. . . . “

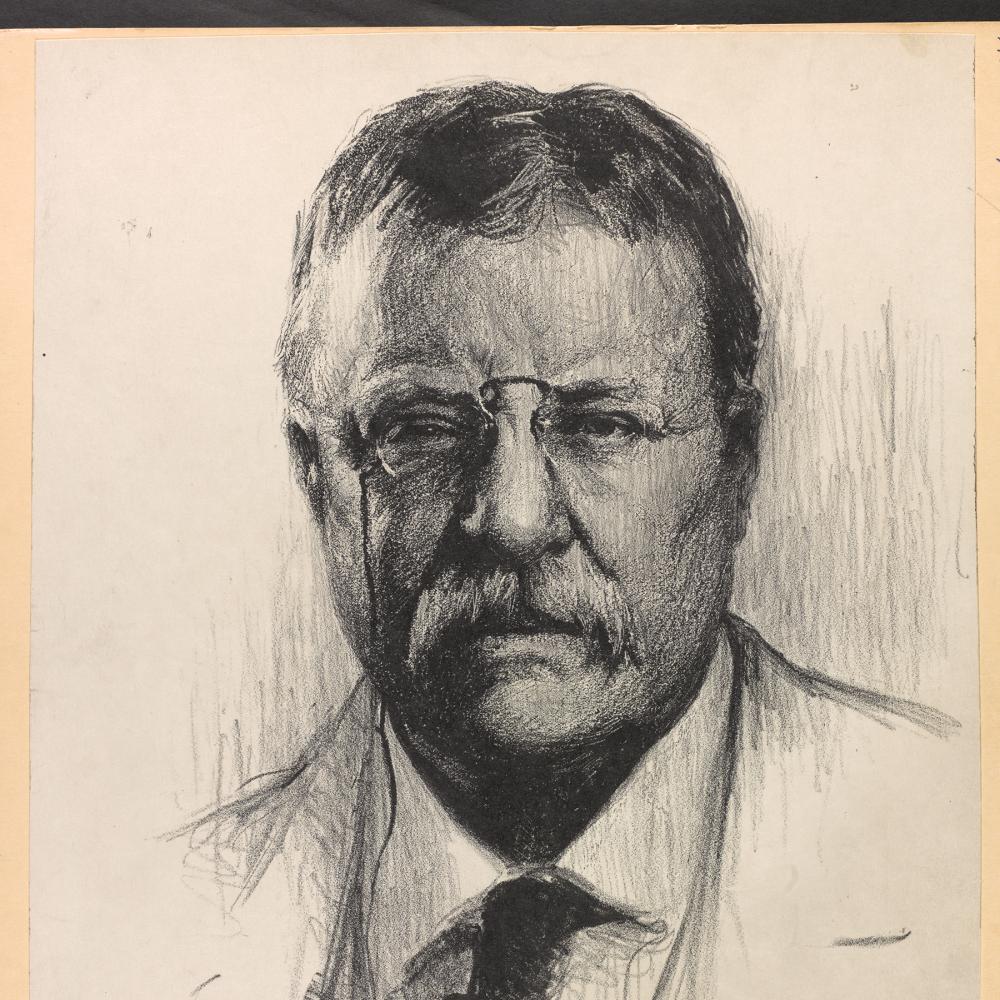

Roosevelt made it out of the Amazon, though thirty-five pounds lighter and leaning on a cane. New lines etched his face and the familiar boom was gone from his voice. The changes to the former president’s appearance were so stark that the New York Times ran before and after pictures. But Roosevelt had not lost his flip humor. When a reporter asked about his health, he replied, “I am worth more than several dead men yet.”

Before he could stand beside a slide projector and present his findings about his Amazon trip, however, Roosevelt had an appointment to keep. President Woodrow Wilson, his foe from the 1912 election, had invited him to stop in for a chat. Given the reports of his feeble state, Washington journalists were stunned to see Roosevelt bounding up the walk to the White House at a little before three o’clock, cane nowhere in sight. For a half hour, the two presidents sipped lemonade on the South Portico while they talked about books and travel.

Within a few months, politics would once again drive a wedge between the old rivals. As war engulfed Europe, Roosevelt emerged as one of Wilson’s sharpest and most persistent critics. He disagreed with Wilson’s decision to keep the United States neutral and loathed the president’s reluctance to prepare American forces for war. Looking for allies, Roosevelt found one within the Wilson administration, a young, up-and-coming Democrat serving as assistant secretary of the Navy. His name was Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Together, the Roosevelt cousins would press the case for preparedness in a common effort that shows two men at very distinct stages in life: one beginning the long climb of a great political career, the other on his way down from those very same heights. As the new Ken Burns documentary, The Roosevelts, points out, Teddy and Franklin had much more in common than a surname.

New York Cousins

The fifty-five-year-old Teddy Roosevelt who strode into Wilson’s office was searching for a way to give meaning to his remaining years. The problem was he’d done so much already. He’d presided as police commissioner of New York City and served as assistant secretary of the Navy. During the Spanish-American War, he saddled up the Rough Riders and fought with verve in Cuba. Next came the governorship of New York, the vice presidency, and, following the assassination of William McKinley, the presidency. Teddy was only forty-two when he put his hand on the Bible and swore to faithfully execute the office of the president. He won the White House on his own in 1904 and picked up a Nobel Peace Prize in 1906 for negotiating the end of the Russo-Japanese War. After leaving the White House, he engaged his wanderlust in Africa and Europe, and, deciding he wasn’t done with politics, stood again for the presidency in 1912, this time as the candidate of the progressive Bull Moose Party. After losing to Wilson, the restless adventurer explored the Amazon.

Through good times and bad, Teddy was a family man. He lost his first wife shortly after she had given birth—and his mother some eleven hours earlier to typhoid. Afterward, he saddled a horse and worked as a cattleman on the Dakota plains, riding out his grief on the unforgiving landscape. He then fell in love with Edith, a striking, scholarly-minded woman who became the love of his life. She claimed Teddy’s daughter, Alice, as her own, and bore him five more children —Theodore, Kermit, Ethel, Archibald, and Quentin. Now grandchildren were beginning to fill the halls of Sagamore Hill, the Roosevelt home on Long Island’s Oyster Bay.

Teddy’s affinity for marriage and family shines through in the note he wrote upon learning that Franklin had become engaged to his niece Eleanor. “I am as fond of Eleanor as if she were my daughter; and I like you, and trust you, and believe in you. No other success in life—not the Presidency, or anything else—begins to compare with the joy and happiness that come in and from the love of the true man and the true woman.”

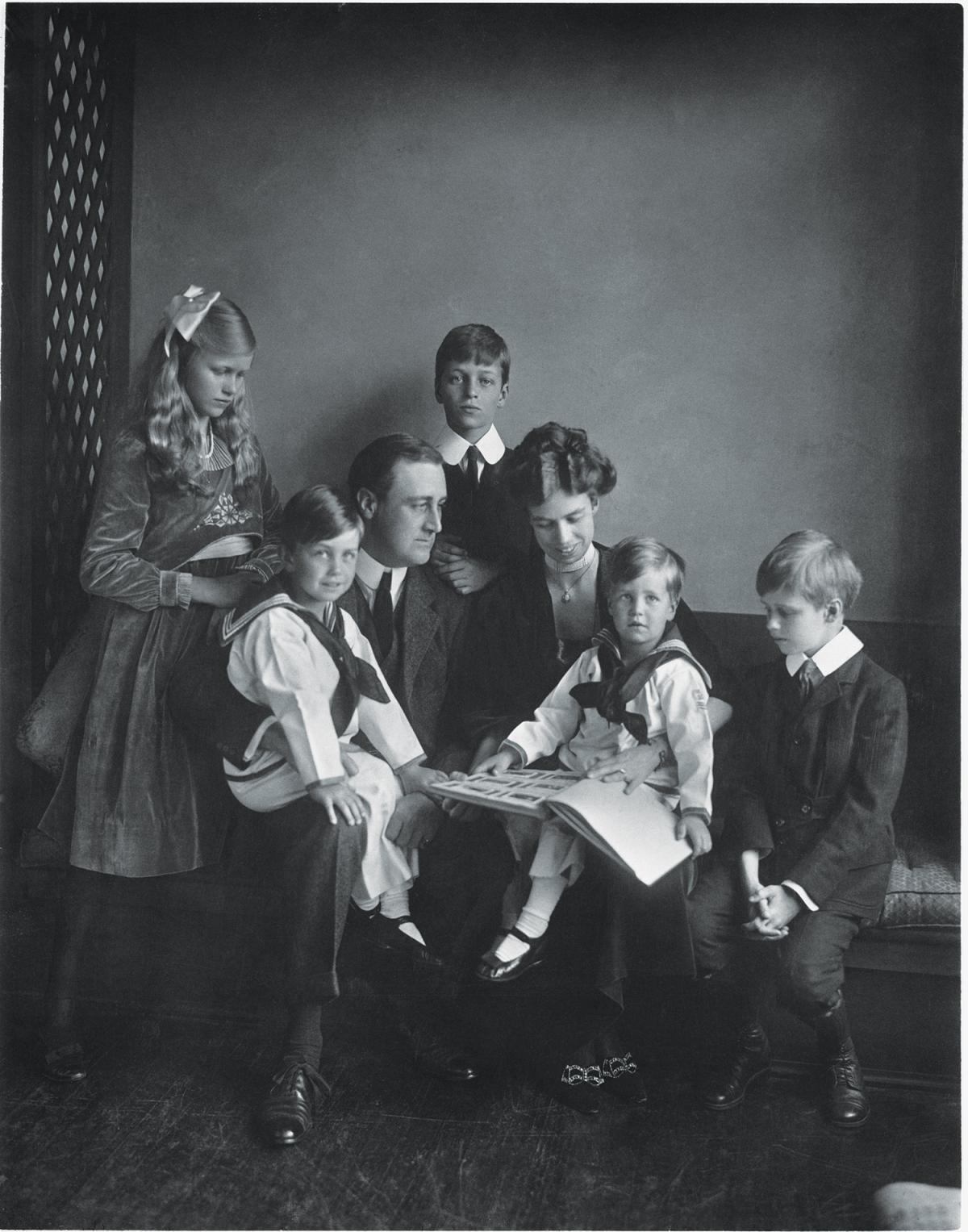

Teddy’s blessing surely meant a lot to Franklin, who was in awe of his fifth cousin. From his boyhood home in Hyde Park, a small town on the Hudson River, Franklin followed Teddy’s exploits, seeing them as a blueprint for success. Like Teddy, he attended Harvard. Like Teddy, he wore a pince-nez instead of standard glasses. He even adopted some of Teddy’s favorite phrases, such as “de-e-e-lighted!” and “bully!” Franklin secretly courted Eleanor, his distant cousin, while attending Harvard, the romance beginning after a chance meeting on a train. They were married on Saint Patrick’s Day of 1905, timing the wedding so that President Roosevelt could give the bride away. Having wooed under the strictures of Victorian morals, their first kiss came at the altar. They eventually had six children—just like Teddy—but only five survived infancy.

Franklin studied law at Columbia, like Teddy, and decided to run for the New York State Legislature, like Teddy. Franklin also embraced progressive politics, but he came to it as a Democrat. Before embarking on his first campaign, Franklin asked for Teddy’s blessing—and received it. “Franklin ought to go into politics without the least regard as to where I speak or don’t speak,” Teddy wrote his sister. Nevertheless, Teddy lamented that his cousin wouldn’t make being a Republican a Roosevelt tradition.

Franklin won the election in 1910 and in 1912 too. He also caught the eye of the national Democratic party, which noted his spirited support of Wilson. When Franklin and Eleanor attended Wilson’s inauguration in Washington, D.C., Franklin was offered the job of assistant secretary of the Navy. He jumped at the opportunity and, at thirty-one, became the youngest person in history to hold the office. He’d also bested his cousin by seven years. “I am very much pleased that you were appointed as Assistant Secretary of the Navy,” Teddy wrote Franklin. “It is interesting to see that you are at another place which I myself once held.” Franklin found his new job an easy fit, settling into the rigors of overseeing shipbuilding programs and procurement. The captains and admirals forgave his eccentricities—such as creating a uniform for himself, despite being a civilian—after discovering he was a crack sailor.

A Great Tragedy Impends

On June 28, 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a Serbian nationalist, stood five feet from Franz Ferdinand, the Archduke of Austria, and shot him in the jugular. The assassination in Sarajevo set in motion a series of telegrams, demands, and alliances. By August, Germany had declared war on France and Russia; Britain had declared war on Germany; and Russia had declared war on Austria-Hungary. Lines were drawn as the Allies—Britain, France, and Russia—squared off against the Central Powers—Germany and Austria-Hungary.

“The situation in Europe is really dreadful. A great tragedy impends,” Teddy wrote his youngest son, Quentin. Because it was an election year, Teddy remained quiet, even as Germany rolled through Belgium, lest he give the Democrats ammunition. Behind the scenes, he preached the importance of preparedness. He even lobbied an old Harvard classmate who had sway with Colonel House, Wilson’s key adviser, to convince the president to prepare the country for war. “I wish you would get him to assemble the fleet and put it in first-class fighting order, and to get the army up to the highest pitch at which it can now be put,” Roosevelt wrote. “No one can tell what this war will bring forth.” Franklin found the wait-and-see attitude of the Wilson administration equally frustrating. “I went straight to the Department, where, as I expected, I found everything asleep and apparently utterly oblivious to the fact that the most terrible drama in history was about to be enacted,” he wrote Eleanor.

Franklin also had a more personal battle to fight. In mid August, he impulsively agreed to run for New York’s vacant U.S. Senate seat. Believing he wouldn’t face any opposition for the Democratic nomination, he spent the rest of the month summering with his family. At the last minute, Tammany Hall put up a candidate: James W. Gerard, the U.S. ambassador to Germany. Gerard’s efforts to help Americans stranded in Germany by war had generated a flood of good press. With Gerard unable to leave his post, Franklin debated a ghost and stumbled on the campaign trail. He could deliver a cracking rant about Tammany Hall corruption but fumbled New York issues.

As Franklin stumped through New York, Teddy wrote a series of articles about the war. With the fighting in full swing in Europe, he could no longer hold his tongue. Likening the conflict to the sinking of the Titanic, TR argued that the nation needed “to safeguard ourselves against such a disaster as has occurred in Europe.” “The prime duty of the moment is therefore to keep Uncle Sam in such a position that by his own stout heart and ready hand he can defend the vital honor and vital interest of the American people,” he wrote.

In late September, Franklin took a beating, receiving 76,888 votes to Gerard’s 210,765. He was shortly back in Washington, preparing for his next foray. In mid October, he released a statement to the press detailing the Navy’s poor state of readiness. Because of a shortage of 18,000 men, only 21 out of 33 battleships could be put into service. Another 75 ships had only half a crew or less. And 38 ships were out of commission altogether. The robust force that Teddy had helped construct as assistant secretary of the Navy and as president was a shadow of its former self. Franklin released the memo while his boss, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, was out of town and without his permission. When Daniels returned, Franklin received a severe dressing-down, but somehow managed to keep his job. As penance, he had to publicly disavow the memo: “I have not recommended 18,000 more men nor would I consider it within my province to make any recommendation on the matter one way or the other.” Between the primary defeat and the disavowal, Franklin was learning the rigors of political humiliation in a very public way.

Although American sentiment—and the Roosevelts’—favored the Allies, Wilson and his cabinet pursued a neutral course during the first four months of the war. In a speech on December 8, 1914, Wilson reaffirmed that position for the foreseeable future. “We are, indeed, a true friend to all the nations of the world, because we threaten none, covet the possessions of none, desire the overthrow of none,” he told Congress. “Our friendship can be accepted and is accepted without reservation, because it is offered in a spirit and for a purpose which no one need ever question or suspect. Therein lies our greatness. We are the champions of peace and of concord.”

The Court of Opinion

On the morning of April 19, 1915, rain pattered against the windows of the courthouse in Syracuse, New York. Teddy sat in the defendant’s chair accompanied by two of the best New York lawyers that money could buy. Across the aisle sat William Barnes and his own pair of high-priced attorneys. Roosevelt’s famously bombastic rhetoric had landed him in court. Barnes, the former chair of New York’s Republican State Committee, had filed a libel suit over Teddy’s claim that Republican and Democratic leaders of New York regularly colluded on elections and political appointments. Barnes wanted $50,000 in damages and to publicly salvage his reputation. To win the trial, Teddy’s attorneys would have to prove that he had been telling the truth.

The combined witness list for both sides ran to one hundred, but the star of the proceedings was Teddy, who spent days on the witness stand. As the attorneys asked question after question about the tangled web of New York politics, it became clear to those in the courtroom that age was catching up with Roosevelt. His famous photographic memory had grown blurry, and he mixed up facts and figures. Testifying proved both emotionally draining and publicly humiliating. For a man who excelled at the rough-and-tumble of debate, the courtroom—with rules for everything from procedure to admissible evidence—proved an unfriendly arena. With each passing day, his chances of winning seemed to fade.

While many of Teddy’s friends shied away from serving as witnesses, Franklin stepped forward. Here was a chance to aid the man he idolized. When asked by Teddy’s attorney to explain their relationship, Franklin replied: “Fifth cousin by blood and nephew by law!” A big grin consumed his face. Franklin testified that he had witnessed first-hand collusion by Barnes and his Democratic counterpart while serving in the New York legislature. “I shall never forget the capital way in which you gave your testimony,” Teddy wrote Franklin after the trial.

When the trial concluded for the day on May 7, the courtroom emptied to the news that the R.M.S. Lusitania, bound for Liverpool from New York, had been torpedoed by a German submarine. The unannounced attack sent 1,198 passengers, including 128 Americans, to their deaths in the cold blue waters off southern Ireland. By torpedoing a passenger ship, Germany had changed the tenor of battle in the Atlantic and challenged the idea of freedom of the seas.

Around midnight, an enterprising reporter for the Associated Press rousted Teddy from bed, asking for a quote. Roosevelt had anguished earlier in the evening over what to say if asked for a comment. Aside from his pro-Allied stance, he had a more immediate concern. At least two members of the jury had last names that sounded German. A virulent rant against Germany could turn those jurors against him. When the reporter relayed the death toll, Teddy threw caution aside. “This represents not merely piracy, but piracy on a vaster scale of murder than the old-time pirates ever practiced. . . . It seems inconceivable that we can refrain from taking action in this matter, for we owe it not only to humanity but to our own national self-respect.” Wilson protested the sinking, but the United States still remained neutral.

After five nail-biting weeks, the jury found for Roosevelt. When the verdict was announced, the courtroom erupted into applause and cheers. Convinced he was going to lose, Teddy found the verdict “utterly unexpected.” Trying to hold back tears, he thanked the jurors for their service, shaking their hands, swearing that he would give them no cause to regret it.

The verdict had left Teddy victorious, but humbled. He received another, unintentional, reminder of his declining state when he arrived home at Sagamore Hill and discovered that Edith and Archie had bought him a “magnificent” horse. “But, alas, they had failed to realize that a horse I would have liked thirty years ago and that you or Ted or Archie would like now would not be a horse that I could handle at present,” he wrote his son Kermit. “Before I could get my right foot into the stirrup, as I move slowly and clumsily, I was pitched off and broke two ribs.”

Going Rogue

Teddy wasn’t the only Roosevelt suffering ill health. In July 1915, Franklin’s appendix burst. Worried about his young assistant, Daniels sent him on the secretary’s yacht to Campobello, an island off the coast of Maine where the Roosevelts summered, to recover. After five weeks under Eleanor’s care, Franklin returned hale and hearty to Washington. Once again, he used an absence by Daniels to push preparedness, announcing the creation of a “National Navy Reserve.” The force of fifty thousand would consist of retired officers and former enlisted men of the Navy, members of the Coast Guard, and civilians with sailing experience. “Any amateur operator, any yachtsmen or motorboat enthusiast, in fact, any citizen with intelligence and application could learn how to fit into some place where he might be needed,” read the statement.

Luckily for Franklin, Daniels agreed with the need for the reserve—and was willing to forgive yet another transgression. Daniels also looked aside or preferred to remain oblivious to the fact that Franklin was feeding his cousin and other preparedness advocates, including Senator Henry Cabot Lodge and Congressman August Gardner, information about the state of the Navy. If Wilson’s policies came back to haunt the nation, Franklin wanted those outside the administration to know he had worked to mitigate their effects.

Over the next year, Teddy continued his assault on Wilson, pleading with the administration to take more steps like readying the naval reserve. He recognized that his stance did not reflect the mood of the public, making him feel both useless and an outsider. It irked him that Wilson had “made up his mind that the bulk of our people care for nothing but money getting, and motors, and the movies, and dread nothing so much as risk to their soft bodies, or interference with their easy lives.”

As the presidential election of 1916 approached, Teddy’s rhetoric packed additional political punch. While Wilson campaigned on the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War,” Teddy hammered him for not coming to the aid of Britain and France. As German submarine attacks against neutral ships mounted and the butcher bill from the Battle of the Somme grew to hundreds of thousands, Wilson’s refusal to aid the Allies looked even more cowardly. American prestige and self-respect declined by the day. Teddy’s nationalism also reached new heights as he ranted against what he called “hyphenated-Americans” and urged that German language instruction be removed from public schools. Believing that a Republican candidate had the best chance of ousting Wilson, he abandoned the floundering Bull Moose Party, which he helped found, and threw his support behind Charles Evans Hughes, the progressive-minded Supreme Court judge. On the campaign trail for Hughes, Teddy minced no words denouncing Wilson’s foreign policy. Hughes asked him to soften his rhetoric, fearing that he might lose immigrant votes, but Teddy persisted.

When he learned that Wilson had eked out a narrow victory, Teddy lamented to his sister that “we are passing through a streak of yellow in our national life.”

The Yanks are Coming!

Wilson reclaimed the White House by touting isolationism, but as 1917 progressed that policy became untenable. After Germany declared unrestricted submarine warfare against any ship in the Atlantic, Wilson severed relations with Berlin. Next came the Zimmermann telegram, which detailed Germany’s offer to give Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico to Mexico if it joined the Central Powers should the United States join the Allies. Despite evidence of German duplicity, Wilson still hesitated to call for war.

“My God, why doesn’t he do something? If he does not go to war with Germany [now] I shall skin him alive,” wrote Teddy. When the German Navy torpedoed three American merchant ships on March 18, Wilson realized he had run out of options.

On the evening of April 2, 1917, a somberly dressed Wilson appeared before a joint session of Congress to ask for a declaration of war. Daniels and Franklin sat in the front row on the House floor, while Eleanor watched from the gallery. Small American flags had been distributed to members, dotting the chamber with pops of red, white, and blue. “The present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind,” he told Congress. “It is a war against all nations.” With a solemn heart, he asked Congress to “make the world safe for democracy” and declare war against “Imperial Germany.” “It is a fearful thing to lead this most peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance. But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things we have always carried nearest our hearts.”

Congress declared war on Germany four days later.

After thirty-six months of teeth-gnashing and hope, Teddy and Franklin had finally gotten their war. Now, they just had to figure out a way to fight on the frontlines.

Franklin called Wilson’s speech “an inspiration to every true citizen no matter what his political faith.” He immediately asked to go overseas, but Wilson said no. He was needed stateside. “Neither you nor I nor Franklin Roosevelt has the right to select the place of service to which our country has assigned us,” Wilson told Daniels. Instead, Franklin helped the Navy expand from 60,000 sailors to nearly 500,000 by the end of the war. The fleet grew from 197 ships to more than 2,000. He also pushed through a scheme to deploy a minefield between Scotland and Norway to snare German submarines. More than 71,000 mines were placed in the North Sea.

Teddy’s luck wasn’t any better. On April 10, eight days after the speech, he paid a call on Wilson at the White House. Despite the verbal hostilities of the previous years, the two presidents chatted amiably for forty-five minutes. Teddy assured Wilson that “what I have said and thought, and what others have said and thought, is all dust in a windy street if we can make your message good.” Then he asked for permission to raise a contingent of volunteers to serve in France. It would take several months for the American Expeditionary Force to be ready to deploy to Europe, but the volunteers could be assembled within a matter of days, just like in the Spanish-American War. And he could lead them into battle and raise the morale of both the nation and the Allies!

When he left the White House, Teddy casually mentioned the regiment to the reporters assembled outside the gates. Within hours Washington buzzed with news of another Roosevelt regiment. Franklin also arranged a private meeting between Teddy and Newton D. Baker, the secretary of war. Editorials across the country sang the praises of the idea. But the regiment was not to be. Wilson worried about the challenge Teddy, as a rejuvenated war hero, would pose to the Democrats in 1920. Wilson and other segregationists also did not like inclusion of African Americans in the regiment. None of this could be said, so they denied Teddy’s request on military grounds. He was not a professional soldier and he was not conversant with recent innovations in warfare.

The regiment was a grand romantic scheme with little basis in reality. Teddy, with his failing eyesight, joints creaking from arthritis, and a portly fifty-eight-year-old body, had no business leading men into battle. Nevertheless, he took the news hard. “This is a very exclusive war and I have been blackballed by the committee on admissions,” he wrote a friend. He consoled himself with seeing his four sons off to war, preaching the importance of patriotism, and playing with his grandchildren.

In the summer of 1918, Franklin finally made it to the front, having convinced Daniels to let him conduct an inspection tour in Europe. It was also his debut on the international stage, another rung up the ladder of his political career. In Britain, he met King George V and Prime Minister David Lloyd George, and had a passing encounter with First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill. (It irked Roosevelt years later to learn that Churchill didn’t remember their meeting.) In France, he met Premier Georges Clemenceau and Marshal Joseph Joffre, toured the battlefields, and checked in on Teddy’s wounded sons. A German shell had shattered Archie’s knee and elbow, while Ted had been gassed. From France, he traveled to Italy, meeting with his naval counterparts, and then it was back to London. Before the ship left for home in early September, he wrote Eleanor of his intention to seek a command. “Somehow I don’t believe I shall be long in Washington. The more I think of it the more I feel that being only 36 my place is not at a Washington desk, even a Navy desk. I know you will understand.”

As the ship made its way across the Atlantic, Franklin fell ill, suffering from a debilitating combination of Spanish influenza and double pneumonia. Like Teddy, he sweat his way through a fever that would almost end his life. The flu cut a deadly path through the crew and passengers, resulting in a series of funerals at sea, but Franklin managed to survive. He arrived in New York so frail that he needed help getting off the ship and up the stairs to his mother’s townhouse. Eleanor’s elation at having her husband home and alive evaporated when she unpacked his luggage. There she discovered a cache of love letters from Lucy Mercer, her former social secretary. Franklin and Lucy were having an affair. “The bottom dropped out on my world,” Eleanor would later say. “I faced myself, my surroundings, my world, honestly for the first time.”

The affair marked yet another departure between Franklin and his idol and raised the specter of divorce. There are competing accounts of who threatened what, but it is generally agreed that Eleanor offered to give Franklin his freedom. Sara, Franklin’s domineering mother, wouldn’t stop Franklin from leaving his wife, but she would cut off all financial support. Getting divorced, however, would kill any possibility of Franklin becoming president. Voters would not look kindly upon a man who left his wife and five children for a woman who had lived in their household for three years. Franklin chose his family and his ambitions, vowing never to see Lucy again.

As Franklin set about repairing his life, working to bridge the loss of trust and security, Teddy discovered there was one loss for which there were no easy remedies. He had urged his sons to enlist in the war, to fulfill their duty as men, to experience the joy and terror of battle. One of them would not come home. Teddy’s youngest son, Quentin, joined the Army’s 95th Aero Squadron, quickly displaying the same thirst for danger as his father as he flew patrols over the trenches that scarred the French countryside. Quentin’s luck ran out on July 14, 1918, when his plane crashed behind German lines. Three bullets penetrated the cockpit. Two bullets pierced his head. German airmen buried Quentin on the site where he crashed. When the Army offered to return the body, the Roosevelts declined. “We greatly prefer that Quentin shall continue to lie on the spot where he fell in battle, and where the foemen buried him,” wrote Teddy.

Old Lion, New Lion

On November 11, 1918, German officials signed an armistice in a train car outside Compiègne, a small village in France, ending the Great War. American entry, bringing with it men and matériel, had tipped the scales in favor of the Allies. After the war, Teddy and Edith hoped to visit Quentin’s grave and place a small marker, but they never made the trip. On the day of the armistice, Teddy checked himself into a hospital. The pain he’d been experiencing in his legs had grown steadily worse, making it difficult and sometimes impossible to walk. He’d remain there through December, receiving visitors and sending off letters to British and French statesmen arguing against Wilson’s Fourteen Points, which he mocked as “Fourteen Scraps of Paper.” He also spoke of making another run for the White House in 1920, making plans and dreaming big to keep the reality of his poor health from crushing his spirit. Teddy made it back to Sagamore Hill for the holidays, leaving the hospital on Christmas morning to avoid attracting the attention of the press who had been playing doctor from afar. On January 6, 1919, he died after suffering a pulmonary embolism.

“The old lion is dead” read the cable Archie sent to his brothers.

The news of Teddy’s passing reached Franklin and Eleanor in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Franklin had been tasked with overseeing the dismantling of the Navy’s European bases and Eleanor was coming along. They had patched up their marriage, but much work remained to be done. Franklin took solace in the fact that Teddy hadn’t suffered a long illness.

With Teddy’s death, Franklin became the Roosevelt spokesman for progressive ideas. In 1920, the Democrats recruited him to run as vice president alongside James Cox, the governor of Ohio. By receiving the nomination, he had once again bested his cousin Teddy, this time by four years. The Cox-Roosevelt ticket lost to Warren Harding. The White House would have to wait. After battling polio, which left him paralyzed from the waist down, Franklin returned to the political fray. He was elected governor of New York in 1928, and four years later he won the White House at the age of fifty. Franklin would serve four terms—two more than Teddy—and steer the nation through the Great Depression and another catastrophic war.

Franklin broke his promise to never see Lucy Mercer again. She was with him when he died of a stroke on April 12, 1945.

This article was updated on October 1, 2014, to correct information about the R.M.S. Lusitania, which was headed to Liverpool from New York, not the other way around.