Archibald Motley (1891–1981) was born in New Orleans and lived and painted in Chicago most of his life. But because his subject was African-American life, he’s counted by scholars among the artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

Many of Motley’s favorite scenes were inspired by good times on “The Stroll,” a portion of State Street, which during the twenties, the Encyclopedia of Chicago says, was “jammed with black humanity night and day.” It was part of the neighborhood then known as Bronzeville, a name inspired by the range of skin color one might see there, which, judging from Motley’s paintings, stretched from high yellow to the darkest ebony.

There was more, however, to Motley’s work than polychromatic party scenes. The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University has brought together the many facets of his career in “Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist.” As a result we can see how the artist’s early successes in portraiture meld with his later triumphs as a commentator on black city life.

First we get a good look at the artist. Near the entrance to the exhibit waits a black-and-white photograph. Motley is highly regarded for his vibrant palette—blazing treatments of skin tones and fabrics that help express inner truths and states of mind, but this head-and-shoulders picture, taken in 1952, is stark. He stands near a wood fence. Behind him is a modest house. Above the roof, bare tree branches rake across a lead-gray sky. Motley is fashionably dressed in a herringbone overcoat and a fedora, has a cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth, and looks off at an angle, studying some distant object, perhaps, that has caught his attention. His gaze is laser-like; his expression, jaded.

“Portraits and Archetypes” is the title of the first gallery in the Nasher exhibit, and it’s where the artist’s mature self-portrait hangs, along with portraits of his mother, an uncle, his wife, and five other women. In Mending Socks (completed in 1924), Motley venerates his paternal grandmother, Emily Motley, who is shown in a chair, sewing beneath a partially cropped portrait.

Born into slavery, the octogenerian is sitting near the likeness of a descendant of the family that held her in bondage. She appears to be mending this past and living with it as she ages, her inner calm rising to the surface. George Bellows, a teacher of Motley’s at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, advised his students to “give out in one’s art that which is part of oneself.” In Mending Socks, Motley conveys his own high regard for his grandmother, and this impression of “giving out” becomes more certain, once it has registered.

If Motley, who was of mixed parentage and married to a white woman, strove to foster racial understanding, he also stressed racial interdependence, as in Mulatress with Figurine and Dutch Landscape, 1920. The flesh tones are extremely varied. Light dances across her skin and in her eyes. All this contrasts with the miniature figurine on a nearby table. The torso’s tones cover a range of grays but are ultimately lifeless, while the well-dressed subject of the painting is not only alive and breathing but, contrary to stereotype, a bearer of high culture.

In The Octoroon Girl, 1925, the subject wears a tight, little hat and holds a pair of gloves nonchalantly in one hand. She’s fashionable and self-assured, maybe even a touch brazen. The wide red collar of her dark dress accentuates her skin tones. A woman of mixed race, she represents the New Negro or the New Negro Woman that began appearing among the flaneurs of Bronzeville.

In 1929, Motley received a Guggenheim Award, permitting him to live and work for a year in Paris, where he worked quite regularly and completed fourteen canvasses. He painted first in lodgings in Montparnasse and then in Montmartre. He did not, according to his journal, pal around with other artists except for the sculptor Ben Greenstein, with whom he struck up a friendship. He even put off visiting the Louvre but, once there, felt drawn to the Dutch masters and to Delacroix, noting “how gradually the light changes from warm into cool in various faces.”

Back in Chicago, Motley completed, in 1931, Brown Girl After Bath. The naked woman in the painting is seated at a vanity, looking into a mirror and, instead of regarding her own image, she returns our gaze. It’s a work that can be disarming and endearing at once. The overall light is warm, even ardent, with the woman seated on a bright red blanket thrown across her bench. She somehow pushes aside society’s prohibitions, as she contemplates the viewer through the mirror, and, in so doing, she and Motley turn the tables on a convention.

In depicting African Americans in nighttime street scenes, Motley made a determined effort to avoid simply populating Ashcan backdrops with black people. Instead, he immersed himself in what he knew to be the heart of black life in Depression-era Chicago: Bronzeville. The center of this vast stretch of nightlife was State Street, between Twenty-sixth and Forty-seventh. It was the spot for both the daytime and the nighttime “stroll.” It was where the upright stride crossed paths with the down-low shimmy. It was where strains from Ma Rainey’s Wildcat Jazz Band could be heard along with the horns of the “Father of Gospel Music,” Thomas Dorsey. It was where policy bankers ran their numbers games within earshot of Elder Lucy Smith’s Church of All Nations. And it was where, as Gwendolyn Brooks said, “If you wanted a poem, you had only to look out a window. There was material always, walking or running, fighting or screaming or singing.”

The Liar, 1936, is a painting that came as a direct result of Motley’s study of the district’s neighborhoods, its burlesque parlors, pool halls, theaters, and backrooms. Men shoot pool and play cards, listening, with varying degrees of credulity, to the principal figure as he tells his unlikely tale. The figures are “more suggestive of black urban types,” Richard Powell, curator of the Nasher exhibit, has said, “than substantive portrayals of real black men.” The mood in this painting, as well as in similar ones such as The Plotters and Card Players, was praised by one of Motley’s contemporaries, the critic Alain Locke, for its “Rabelaisian turn” and its “humor and swashbuckle.”

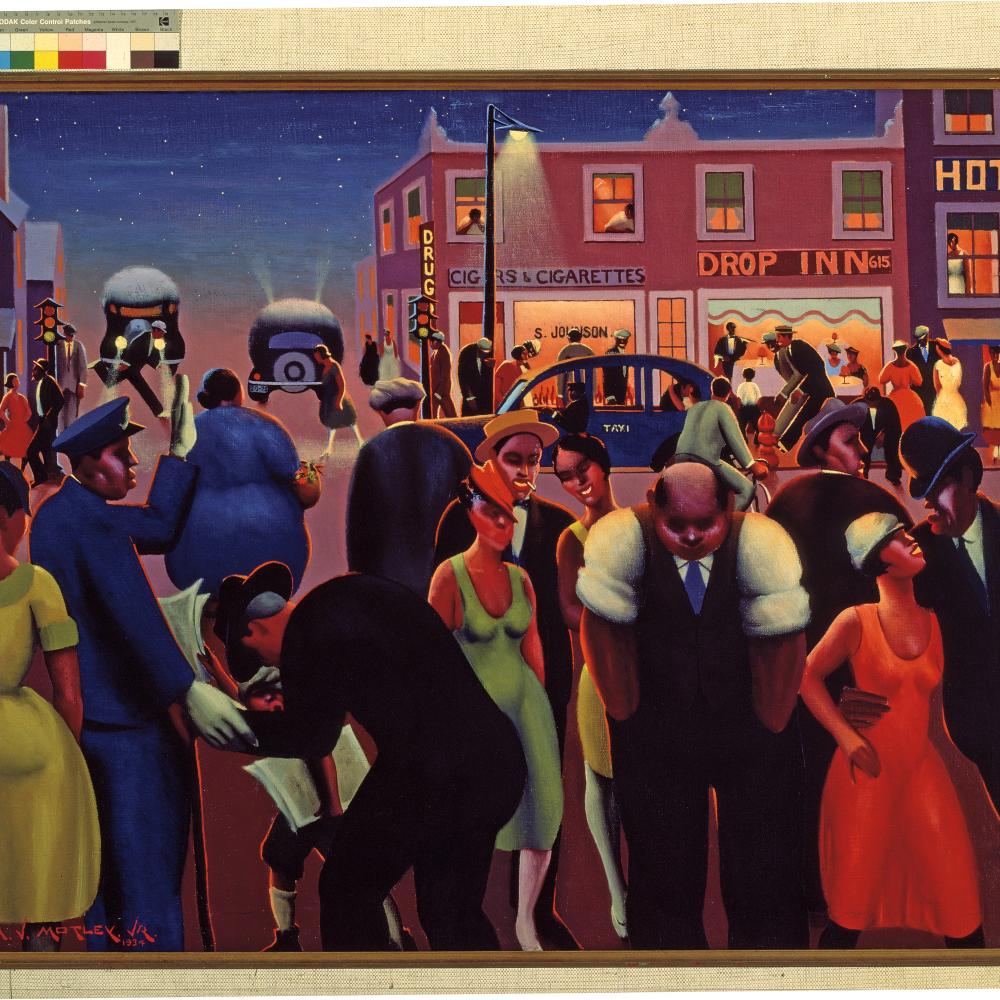

Black Belt, completed in 1934, presents street life in Bronzeville. The crowd comprises fashionably dressed couples out on the town, a paperboy, a policeman, a cyclist, as vehicles pass before brightly lit storefronts and beneath a star-studded sky. One central figure, however, appears to be isolated in the foreground, seemingly troubled. He’s in many of the Bronzeville paintings as a kind of alter ego. Physically unlike Motley, he is somehow apart from the scene but also immersed in it.

The Nasher exhibit selected light pastels for the walls of each gallery—colors reminiscent of hues found in a roll of Sweet Tarts and mirroring the chromatics of Motley’s palette. This is particularly true of The Picnic, a painting based on Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s post-impression masterpiece, The Luncheon of the Boating Party. And Motley’s use of jazz in his paintings is conveyed in the exhibit in two compositions completed over thirty years apart: Blues, 1929, and Hot Rhythm, 1961. They both use images of musicians, dancers, and instruments to establish and then break a pattern, a kind of syncopation, that once noticed is in turn felt.