Poverty Point: Preservation of a Prehistoric World Heritage Site

Poverty Point, aerial photo

Used by permission of Susan Guice

Poverty Point, aerial photo

Used by permission of Susan Guice

The Poverty Point State Historic Site, located in northeastern Louisiana, was recently named by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to its World Heritage List. This is a list of the world’s cultural and natural treasures, properties which are of outstanding value to humanity. Poverty Point is only the 22nd World Heritage site in the United States.

Named for a 19th-century plantation, Poverty Point is home to a prehistoric earthwork complex, one of the largest in North America. It is also considerably older than the earthen mound site at Cahokia in Illinois, also a World Heritage site. Poverty Point was built and occupied from 1,700 to 1,100 BC. According to UNESCO, it is “a remarkable achievement in earthen construction in North America that was not surpassed for at least 2,000 years."

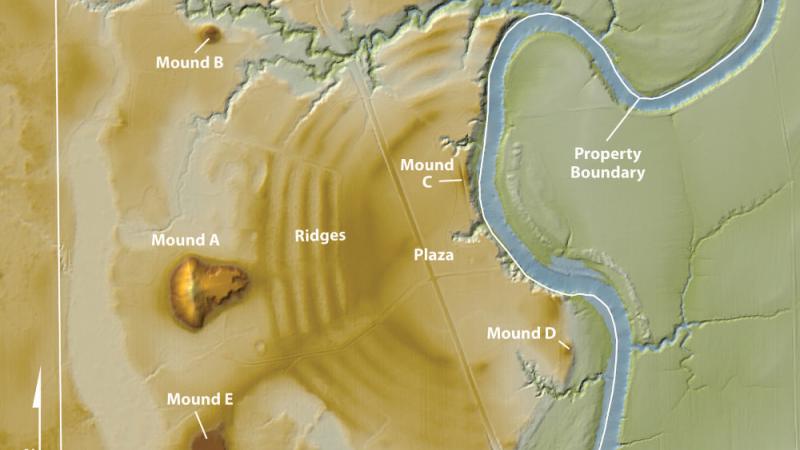

Occupying roughly 350 acres, the monumental core of Poverty Point consists of five mounds, six concentric semi-elliptical ridges separated by shallow depressions, and a central plaza. The largest mound, thought by some to be shaped like a bird, is over 70 feet tall and represents an impressive construction effort by people who lived in this region.

Station Archaeologist Diana M. Greenlee, who is a member of the adjunct faculty at the University of Louisiana at Monroe, notes that Poverty Point was part of a larger cultural complex of mound builders that extended throughout the lower Mississippi River valley. Despite excavations that have uncovered stone tools, pottery, and other artifacts at Poverty Point, relatively little is known about the people who built the mounds. They were not farmers, but rather subsisted through hunting, gathering, and fishing. However, they also obtained goods from as far afield as the southern Appalachians and the upper Midwest.

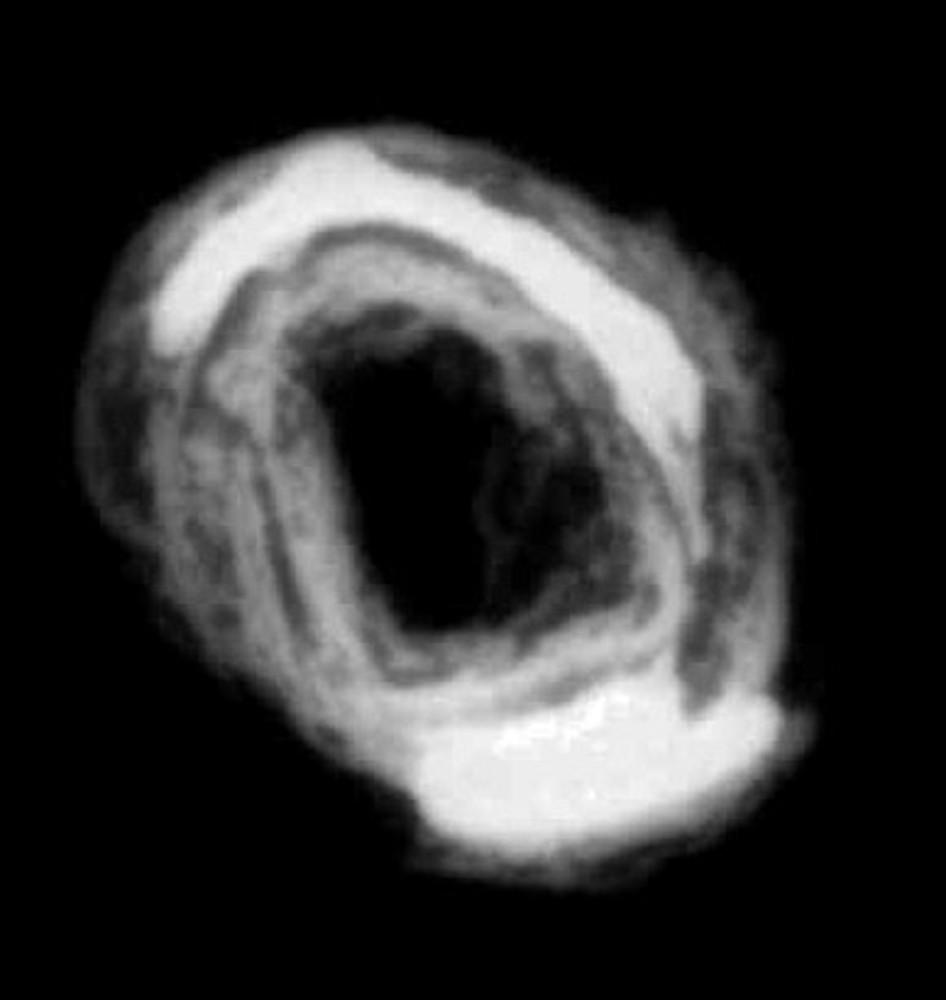

Nearly 200 objects, including beads, pendants, needles, and thin sheets, of copper, long thought to have come from the upper Midwest, have been found at Poverty Point. In 2011-2012, Dr. Greenlee directed a project at Poverty Point supported through a NEH Preservation Assistance Grant. Its goal was to ensure the preservation of these fragile copper artifacts—part of a much larger collection that includes hundreds of thousands of items, mostly made of stone and fired clay. Some 2,000 artifacts are currently on display at a museum at Poverty Point. The remainder are stored in an archaeological curatorial facility where they are available for research or exhibition.

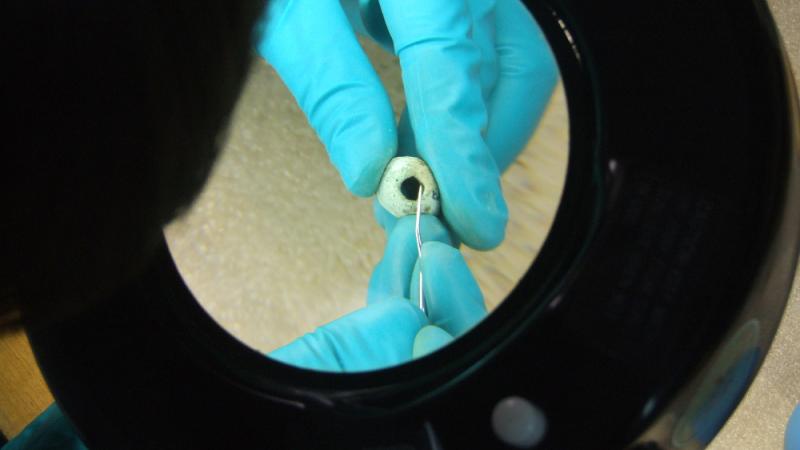

The NEH Preservation Assistance Grant supported visits to Poverty Point by an objects conservator who assessed the current condition of the copper items. The artifacts were photographed and X-rays taken—the latter through an X-ray machine, access to which was donated by a local dentist—to determine their structural integrity. The project team then devised a plan to clean, stabilize, and rehouse the objects in sealed, dry, supportive, micro-climate enclosures.

Preserving prehistoric materials in the hot, humid Louisiana climate is a formidable challenge and requires the careful monitoring of environmental conditions in the museum. In the course of the NEH project, the museum acquired dataloggers—small devices which automatically measure and record temperature and relative humidity in the museum’s gallery and exhibition areas.

Because of the condition assessments, it is clear which copper artifacts are sufficiently robust to withstand different levels of analysis. Greenlee collaborated with Drs. Mark Hill (Ball State University) and Hector Neff (California State University, Long Beach) on nondestructive elemental analysis of a small sample of the most stable copper artifacts. They concluded that the composition of these objects is not consistent with the long-held assumption that they were made of copper from the Lake Superior region. Further analyses are planned to include more geological sources and additional Poverty Point artifacts. The condition assessments made possible by the NEH Preservation Assistance Grant will play a key role in selecting which artifacts to include in the future research.