The Pulitzer Prizes and the National Endowment for the Humanities

Since its inception in 1965, the National Endowment for the Humanities has awarded grants to eighteen authors whose books went on to win the Pulitzer Prize. The list of prize-winning authors grew to nineteen in April 2020, when NEH Public Scholar W. Caleb McDaniel (FZ-250480-16) received the prize in history for Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America (Oxford University Press, 2019). To better understand the Pulitzer, the effort it requires, and its lasting effects on those who win it, I spoke with three additional NEH-supported winning authors: William Taubman (FB-29109-92), Stacy Schiff (FB-34784-98), and Louis Menand (FA-29582-90).

This story begins with McDaniel, Professor of History at Rice University. His Sweet Taste of Liberty examines the life of Henrietta Wood, which was rife with tragedy and triumph: Wood, McDaniel explained, was “born enslaved, freed, re-enslaved, and then emancipated again.” After she gained her freedom the second time, Wood sued her captor for restitution and, miraculously, “won her day in court.” Her story, McDaniel told me, is critical for understanding how the United States “got to where it is,” as well as “helping us,” its citizens, “imagine alternative futures.” And it displays, as Frederick Douglass observed in 1857, that “power concedes nothing without a demand.”

Although his book had already been a finalist for the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize and earned the Avery O. Craven Award, McDaniel was “completely surprised” to have won the Pulitzer. His expectations were so modest that he neglected to watch the online announcement, instead occupying that afternoon with repairs around the house. However “stunned by the news” of his success, McDaniel felt grateful that “more people would learn about Wood.”

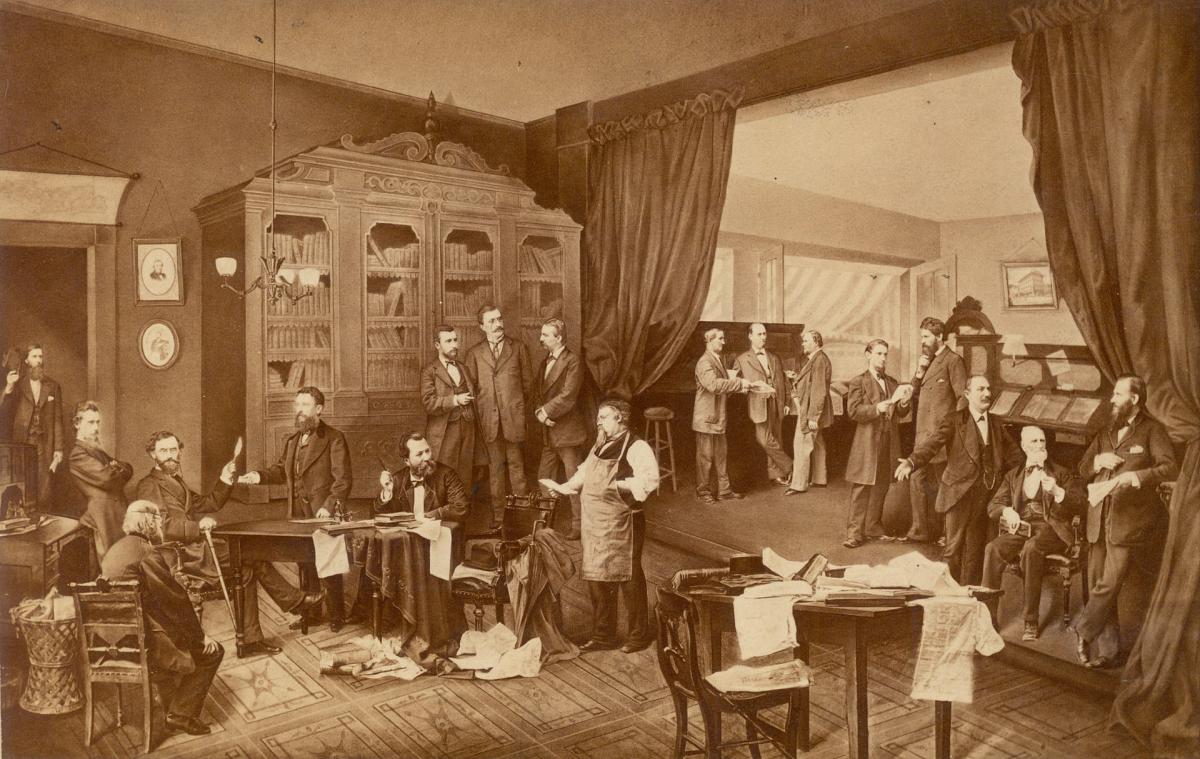

Joseph Pulitzer and his prizes

Over 170 years before McDaniel collected his unexpected prize, Joseph Pulitzer was born in Mako, Hungary in 1847. A plucky young man eager to leave home, Pulitzer traveled to America at seventeen and enlisted in the New York-based Lincoln Calvary. Following his military service, he moved to St. Louis, where he worked various jobs – muleteer being the most unusual – while mastering English. Pulitzer was eventually hired as a reporter by the Westliche Post, and he soon rose to editor. With his modest editorial salary and canny judgement, he purchased the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1878, saving it from collapse. Later, on his return to the East Coast, Pulitzer bought the New York World. There, he championed the populist journalistic style for which he is remembered.

Pulitzer sought to shape public life in other ways as well. He donated to numerous lasting cultural institutions, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and New York Philharmonic. And he promoted endeavors to professionalize and regulate journalism. “The greatest minds of the nation,” he wrote in a May 1904 address to The North American Review, “must realize how indissolubly a pure republic is linked with an upright press.” Through his will, Pulitzer gave permanence to these philanthropic passions. He established a school of journalism at Columbia University, in addition to the annual awards in journalism and letters that now bear his name.

(For more information, visit the official website of the Pulitzer Prizes.)

Past Laureates Taubman, Schiff, and Menand

The mission of the NEH intersects with two Pulitzer Prize categories: United States history and biography by an American author. Three past NEH Fellows and Pulitzer laureates – William Taubman, Stacy Schiff, and Louis Menand – have experienced this convergence first-hand.

William Taubman is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Amherst College and author of Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (Norton, 2003), the first American biography of Nikita Khrushchev. Reflecting on his subject, Taubman emphasized Khrushchev’s distinctive leadership. The Soviet premier often took “idiosyncratic” action, compelling historians to “scrutinize his character” and its “personal, psychological roots.” Taubman himself pored over Khrushchev’s papers, interviewed his “family members, associates, and adversaries,” and even “drew on theories of personality.” Despite these exhaustive efforts, Taubman considered it “wildly irrational” to be optimistic about winning the Pulitzer. Nonetheless, with encouragement from his wife, he dreamt – albeit cautiously, lest he become “hurt by the result.” In April 2004, when the Pulitzer Board announced that Khrushchev had prevailed, Taubman “felt wonderful, not to put too fine a point on it.”

Stacy Schiff, a fellow biographer, echoed Taubman’s sentiments: “It feels magical to win.” Schiff nearly triumphed with her debut book, Saint-Exupéry: A Biography (Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), one of the three finalists. Even so, she lacked the “slightest inkling” that her next, Vera (Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov) (Random House, 1999), was under consideration. “The 2000 Pulitzer,” she recalled, “came as bolt from the blue.” The surprise success of Schiff’s work stems in part from the complexity of its focus, Vera Nabokov. Vera was a keen mind in her own right, but with her celebrated husband, Vladimir Nabokov, she revolutionized 20th-century literature. As Vladimir’s muse and partner, Vera recited his poetry, proofed his fiction, and once “saved Lolita from the flames.” Still, she “categorically denied” any influence on Vladimir’s career. To truly uncover Vera – person and patron – Schiff investigated hidden archives and visited the Nabokov’s friends. One, the artist Saul Steinberg, told her, “You could write about Vera without mentioning Vladimir. But it would be impossible to write about Vladimir without mentioning Vera.”

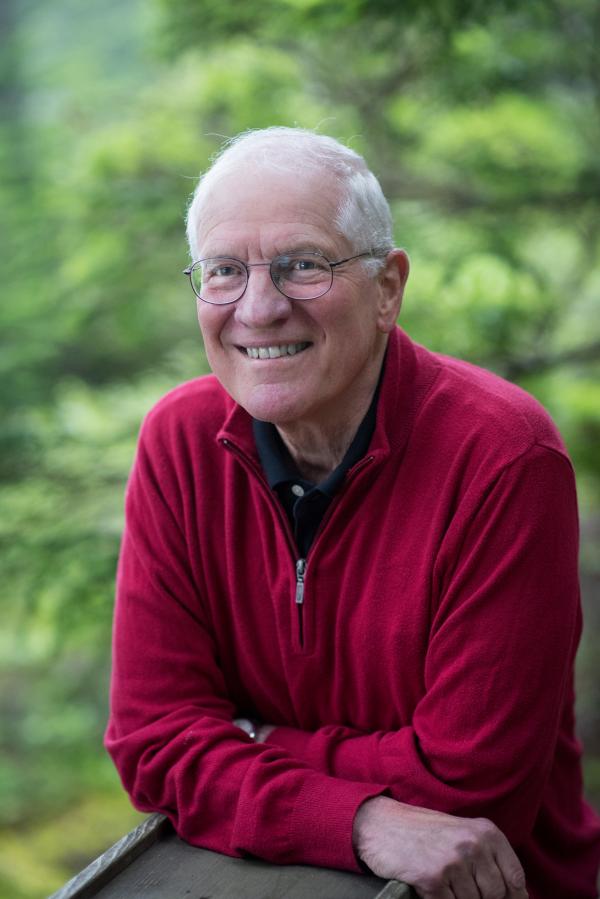

Louis Menand’s The Metaphysical Club (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2001) centers on a different pioneering collaboration, linking jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., psychologist William James, and logician C.S. Peirce. In 1872, the three created a group to explore contemporary philosophy. A new, more practical manner of thought – pragmatism – blossomed from its meetings. Menand, Professor of English at Harvard University, was intrigued by the method, which “could be made to stand for” a greater, post-bellum “shift in American intellectual life.” This turn, he explained, presents a key historical question: “How did one way of thinking or doing things swing over into another?” Though Menand saw The Metaphysical Club as a “plausible candidate” for 2002 prize in history, he “never imagined” a victory. He was, of course, “very happy” to earn his discipline’s “top recognition.” By his estimation, the only comparable award was his 2016 National Humanities Medal, given to him by President Obama in consultation with the NEH. Yet “that one,” he said, “felt undeserved!”

Change after the Pulitzer

Some time removed from their respective victories and in light of McDaniel’s recent achievement, Taubman, Schiff, and Menand assessed the effects of the Pulitzer. Before winning their prizes, each scholar grappled with academic insecurities. Schiff feared biography was an “obsessional, irrelevant, and impossible” occupation. Taubman, meanwhile, questioned the quality of his book and, generally, his writing style. Caught between approachable and academic, he would “occasionally hear a colleague grumble that a brightly written article was ‘just journalism.’” Menand ran into a similar uncertainty: his prose seemed “too highbrow” for a non-specialist audience, but “not quite ‘scholarly’ enough for professors.” The Pulitzer assuaged, if not extinguished, these natural doubts, validating the awardees’ pursuit of public-facing scholarship and their countless hours of toil.

The Pulitzer also led to professional opportunities. Menand was offered “multiple jobs” and “ended up going to Harvard.” Schiff, an independent scholar, discovered that future projects were easier to research, since archivists were a “little more willing to trust” her with fragile documents. With such rich benefits ahead, the past laureates extended simple counsel to new winners: “Enjoy it!”

Recipes for Pulitzer success

The laureates offered advice to prospective authors, too. Familiarity with the administration of the Pulitzer is a worthwhile place to start. The prizes are distributed in a multi-step process, which Taubman described. First, books are nominated for a category by their publishers. The publishers, he noted, “are not chary about submitting quite a few.” Then, a jury reviews these submissions and recommends three finalists without preference. Finally, the Pulitzer Board, responsible for oversight throughout, “actually awards the prize.”

Taubman and Schiff, former jurors themselves, revealed some of the commonalities among awardees. Above all, successful works balance accessibility with academic rigor. “Juries,” Taubman commented, “don’t cotton to any discipline’s jargon.” Rather, “they value good writing along with good scholarship.” Schiff, when evaluating, sought the same thing that a reader might: a “resonant story, profoundly (and invisibly) researched and artfully told.”

Of late, the path to achieving the Pulitzer has widened, as the award encompasses more thematically-diverse inquiry. Schiff pointed out that “for many years, there was a biographical run of ‘great men.’” Now, by contrast, “there are nearly as many recipes for Pulitzer winners as there are for flourless chocolate cake.” McDaniel noticed a comparable broadening in his field: “Black women’s history has not often been highlighted by the prize.” However, by “honoring Henrietta Wood,” the Pulitzer Board recognized that her life matters and is “vital” to study. While McDaniel acknowledged, like Wood might, that “history doesn’t inevitably move in a straight, progressive line,” books on forgotten people and overlooked topics will probably continue to flourish in front of the juries and award committee.

NEH inspires Pulitzer potential

Though masterfully balanced language and a fresh thesis are essential to winning a Pulitzer, Taubman, Schiff, Menand, and McDaniel acknowledged the importance of NEH support as well. When Taubman “needed both funding and confidence,” the Endowment contributed to his project. For that, he was “sincerely grateful.”

The NEH likewise helped Schiff, particularly with travel. During her fellowship, she spent a summer in Switzerland probing the Nabokov archives, located in their son’s basement. On a later trip to Paris, with additional funding from Guggenheim Foundation, she met members of the Russian émigré community and a “shady collector.” The man suggested she steal for him items from the Nabokov papers in exchange for a look at Vladimir’s love letters to a mistress. Schiff “never saw the documents,” maintaining her integrity. But she thanked the NEH for this uncommon encounter and her time abroad, which greatly improved Vera’s biography.

To Menand, the backing of the NEH was an impetus. Following the birth of his first child, he taught “seven courses a year” between Queens College C.U.N.Y. and Columbia. As an NEH fellow (and after with a fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation), he was finally able to devote his energy to research. Despite being “broke” by the end of the grant period, it afforded Menand the flexibility to begin his book. McDaniel, who used NEH support to finish his, sees the Endowment as a “national treasure.”

“In this business,” Schiff reflected, “there are few irrefutable marks of recognition. The Pulitzer is one. An NEH grant – which actually makes the work possible – is another.”

NEH Postscript: The 2021 Pulitzer Prize in History was awarded to Marcia Chatelain for her NEH-sponsored book Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America (Liveright/Norton, 2020), bringing the NEH’s list of prize-winning authors to twenty. Chatelain's book was supported by FA-251663-17.