Herbal Heritage: A Renovation Project for the Sabbathday Lake Shakers

“We have a museum, but we’re not a museum,” Michael Graham, Director at the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village, said recently. “At sites like ours, historic properties are used by others after the culture has disappeared, but [Shaker] culture is still here, guiding the heart and soul and spirit of how we run our public programs—and nested in there is the human connection.” For the Shakers at Sabbathday Lake, Maine, fostering human connection has been the guiding principle of their community for decades. With the help of a $750,000 grant from NEH, the Shakers at Sabbathday Lake will be able to expand their programming and reach even further through the renovation of their Herb House. This renovation will create new opportunities for the two resident Shaker leaders, Brother Arnold Hadd and Sister June Carpenter, and their community partners to engage with new audiences. They will be able to invite their visitors and the local community into the Shakers’ history, traditions, and vision for the future.

Though many people think of the Shakers as an anachronism, a remnant of religious revivalism from the 18th and 19th centuries, they are still a living community of faith. The United Society of Believers was founded by a group of former Methodists in England in 1747. They were originally dubbed “Shakers” in derision by outsiders because of their full-body embrace of ecstatic worship. In 1770, a Believer named Ann Lee experienced a series of visions and from then on was known as Mother Ann, leader of the Shakers. Mother Ann and eight followers left England for the American colonies in 1774, settling first in upstate New York, outside what is now Albany. There, they lived quietly for several years.

On May 19, 1780, smoke from wildfires in Canada darkened the skies over New York and New England, blocking out the sun. Many people interpreted this “Dark Day” as a sign that Judgment Day had come. Shaker missionaries, including Mother Ann Lee and Father James Whittaker, began preaching publicly, attracting both converts and the attention of officials. New York officials, who were suspicious of these English immigrants preaching pacifism in the midst of the American Revolution, arrested and briefly imprisoned Mother Ann Lee and other Shakers. They were released by 1781 and began traveling around New England, preaching, converting new Shakers, and establishing other Shaker communities.

The Sabbathday Lake Shaker Community was established by a group of roving Shaker missionaries in 1783 and quickly grew to about 180 people. The Meetinghouse was the first purpose-built building at Sabbathday Lake, constructed in 1794, followed by the Dwelling House in 1795. Between 1795 and 1805, the community constructed worship spaces and agricultural buildings including barns and mills. Daily life for the Shakers, then as now, is rooted in the rhythms of communal work and the agricultural year. Following the teachings of Mother Ann Lee, they practice gender equality, racial equality, celibacy, communal work and property ownership, and pacifism, embracing her mantra, “hands to work, hearts to God.” They reinforced these beliefs in the 1820s with a set of codes called the Millennial Laws, which laid out rules for daily living—from how to worship to what color to paint the beds (green)—and codified Shaker behavior both within their communities and in the outside world. Shakers believe that their inspiration was to come from within the Church rather than from outside, and so they tried to maintain distance from the outside world.

One way Shakers did interact with the outside world, however, was through agricultural commerce. Shakers, like other colonists, had brought herbs with them from Europe, but they also learned the uses and properties of native plants from Indigenous peoples. The Herb House was built in 1824, as Shakers at Sabbathday Lake and the other Shaker villages across the Northeast and Midwest began to produce herbs commercially for culinary and medicinal use. This was not the Shakers’ only commercial enterprise. They also became well known for their decorative arts, particularly household goods, including flat brooms, spinning wheels, woodenware, lumber, and farm produce, which they sold in large quantities to support their communities.

While the Shakers believe that labor is a spiritual act, they have always understood and grappled with the necessity of interacting with the outside world to support their community. In herb houses across the country, Shakers hung harvested plants to dry and processed and packaged them for medicinal or culinary use. They sold herbs in their local communities and on a larger scale throughout the nineteenth century. However, industrialization, westward expansion, an emerging national economy, and decreasing Shaker populations pushed the Shakers out of the herb business. By 1910, their enterprise had collapsed. Shaker Villages around the country demolished their Herb Houses—except for the one at Sabbathday Lake.

Because the Sabbathday Lake Shakers remained faithful and guided by discerning leaders, they were able to persist, while membership in other Shaker communities declined in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The group continued to grow, dry, and package herbs for sale locally and for the Back-to-the-Land movement of the 1960s. Now, the Sabbathday Lake Shakers sell herbs onsite to thousands of visitors, online to customers around the world, at farmer’s markets, and at Shaker museums in other states. The Herb House is the fourth-oldest building on the property, and the centerpiece of a vision to open the Shaker Village to the community around it.

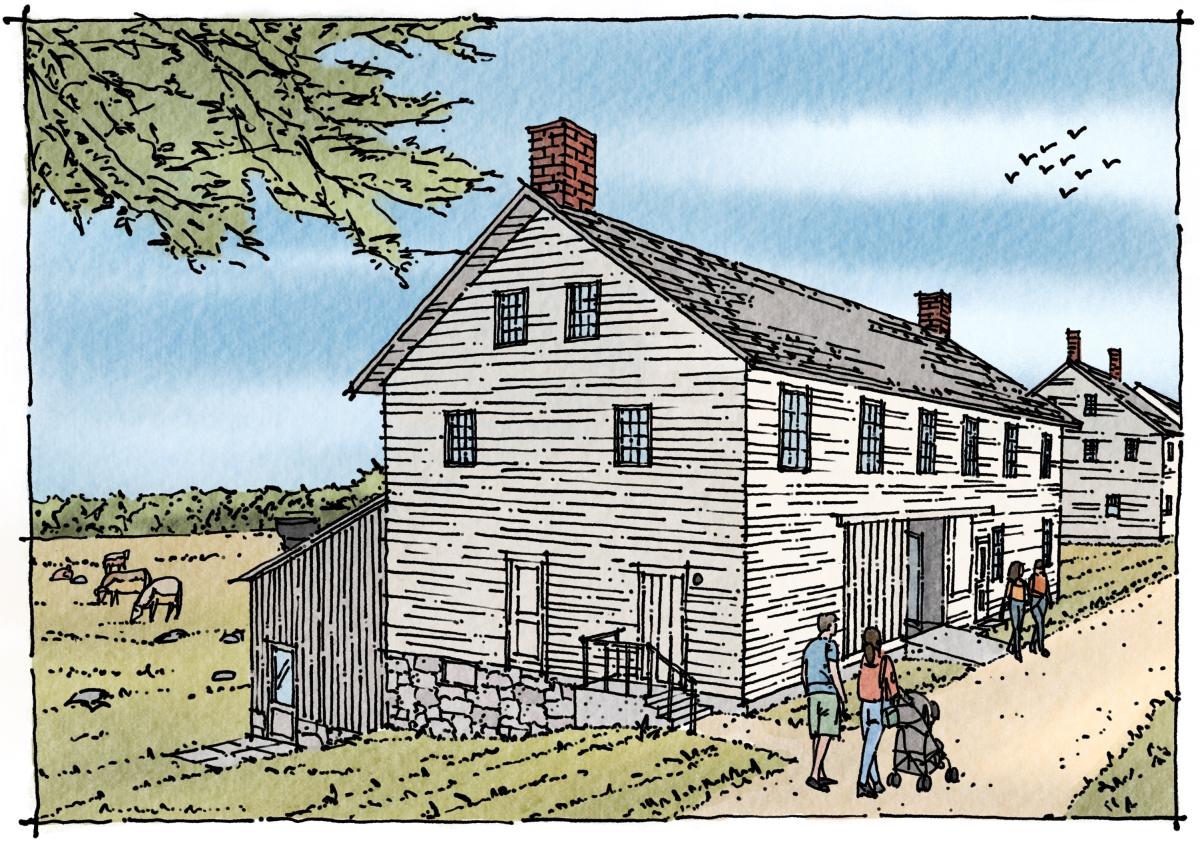

The NEH grant will fund the renovation of the Herb House, which has fallen into disrepair from underuse. Currently, all herb-related operations are in a different building. The Shakers and their nonprofit organization which manages the site, the United Society of Shakers, Inc., intend for the renovated Herb House to be a community hub. In the new space, Shakers, gardeners, volunteers, and community members will cross paths, with visitors coming and going in the midst of the hum of intentional, communal work. The Herb House will feature multipurpose work and learning spaces and an exhibit area—the first permanent gallery at Sabbathday Lake—which will contextualize the Shaker’s long agricultural history.

The most important thing about the Herb House project is that it will allow the Shakers to expand the work they do with the community around them, as Graham described. “We didn’t need another building here restored for museum purposes, we needed a place where this growing community of people around the Shakers could expand and have a home.”

The project will create these much-needed new spaces. A specialized herb production workroom on the second floor will be where a diverse group of people will process and package herbs. The Shakers currently run programs with Personal Onsite Development, Opportunity Enterprises, and the Margaret Murphy Centers for Children that support teenagers and adults with intellectual uniqueness, enveloping program participants in a supportive community while teaching them skills in the herb house, from preparing herbs to using digital scales to weigh and package them. “Just by saying yes [to these programs],” Graham said, “this place [has] the ability to change people’s lives, and build a bigger, stronger community, and advance understanding of who the Shakers were, are, and will be.”

As they planned this project, the Sabbathday Lake Shakers worked closely with architects to adhere to the Shaker tradition of order and communal labor. A multi-use gathering space will be used for meetings, craft and cooking demonstrations, and community organizing. Clear glass dividers that reach from floor to ceiling enable spaces on the ground floor to be closed off from each other acoustically while maintaining the sense of community and communal work that is so important to the Shakers. These spaces, Graham noted, will be “incubator spaces for folks in the community… glass walls mean you’ll be seen and have a chance to share with visitors what you’re doing and why it’s important,” so that budding entrepreneurs and visitors can have “profoundly memorable and meaningful learning experiences both ways.”

The Herb House project is part of the Sabbathday Lake Shakers’ strategic plan, which includes opening nature trails on the 1,700 acres of land that make up the village as well as building a new Visitor’s House and a farmer’s market and café that support traditional artists and aspiring farmers. They are also currently restoring the Great Barn, with the help of a $500,000 grant from the Save America’s Treasures program from the National Park Service. Ultimately, Graham says, what matters is that these spaces invite participation and community engagement, because that’s how Sabbathday Lake will continue to thrive. “We need participation, we need to get people to come here, to see and experience Shaker life and Shaker culture … Once people get here, they start to understand how relevant Shaker life remains. We need people to take action—the whole premise of the project is about work, and work is active, so we need to motivate people to do something to help the Shakers make meaningful contributions.” Construction will take place in 2024, as the Shakers celebrate the 250th anniversary of their arrival in America, as well as the 200th anniversary of the construction of the Herb House.

The Herb House at Sabbathday Lake is not the only Shaker infrastructure project funded by the Office of Challenge Programs. In March 2023, NEH announced the approval of a project to renovate the visitor center and Center for Shaker Studies at Hancock Shaker Village, a museum and former Shaker village in western Massachusetts. In December 2020, NEH awarded a $550,000 Infrastructure and Capacity Building Grant to the Shaker Museum, in Mount Lebanon and Chatham, New York, to construct a climate-controlled collections storage facility within their new museum building.

The Herb House project at the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village exemplifies how humanities projects can be rooted in living communities. NEH Program Officer Tatiana Ausema noted, “This is an example we can point to in order to talk about the humanities in a meaningful way outside the academy—it’s amazing.” The lived humanities at Sabbathday Lake are simple, Graham said. “It’s about people coming together and connecting and growing from those experiences.” The seeds have been planted at Sabbathday Lake, and with the help of NEH, this community will continue to grow and thrive.

The United Society of Shakers, Sabbathday Lake, Inc. was awarded an Infrastructure and Capacity Building Challenge grant (CHA-286603-24) in 2023.

The Infrastructure and Capacity Building Challenge grant program has been discontinued, but visit the Office of Challenge Programs page for more information about other funding opportunities. Contact @email with questions.

![Shaker's worshiping, exercise / Gilbert. New York Mount Lebanon, None. [Place not identified: publisher not identified, between 1790 and 1810]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2023-12/2.jpg?itok=1W8a6q_C)