Archives of the Environment as Humanities Collections and Reference Resources

The Biden Administration has made clear that the current climate emergency is one of its top priorities, pledging “to take swift action to tackle the climate crisis.” Federal agencies have been asked how they will integrate this priority into their work. We in the Division of Preservation and Access (DPA) know that cultural heritage professionals are responding to climate change in many ways, from building energy efficient storage solutions to creating disaster preparedness plans to recovering from extreme weather events. As we search for new ways to adapt and prepare in our current climate emergency, recent turns in Indigenous and environmental studies also have us thinking about what collections themselves can teach us about our relationship with the natural world.

In the middle of the last century, conservationist Aldo Leopold poetically described the relationship between nature and archives while felling an oak tree. “[T]he stump yields a collective view of a century” Leopold reflected and then concluded, “By its fall the tree attests the unity of the hodge-podge called history.”1 Early American historians took Leopold’s poetic musings quite literally and to great effect, fusing their readings of the colonial record with that of the land, increasingly considering it, too, as historical evidence. In his field-defining study, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England, William Cronon combined seventeenth-century descriptions and colonial records of New England with “less orthodox sorts of evidence which historians borrow from other disciplines and have less experience in criticizing . . . . [such as] analyzing tree rings, charcoal deposits, rotting trunks, and overturned stumps to determine the history of several New England woodlands.”2 More recently, Karen Halttunen reminds us that current-day environmental history is, in many ways, an extension of nineteenth-century local histories because “[t]he guiding assumption of these works was that local history had literally taken place on the land. Indeed, local history had actively made place and had in turn been shaped by place.”3 Leopold, Cronon, and Halttunen were right. When we open ourselves to new source pairings—local histories read with piles of sawdust, early American herbaria next to topographies of woodlands, eighteenth-century almanacs next to dendrology—we see that climate research is as much a humanist endeavor as it is a scientific one.

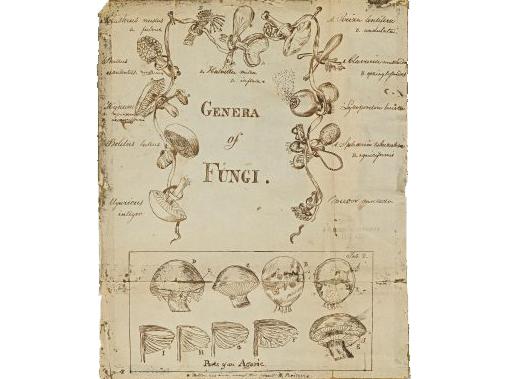

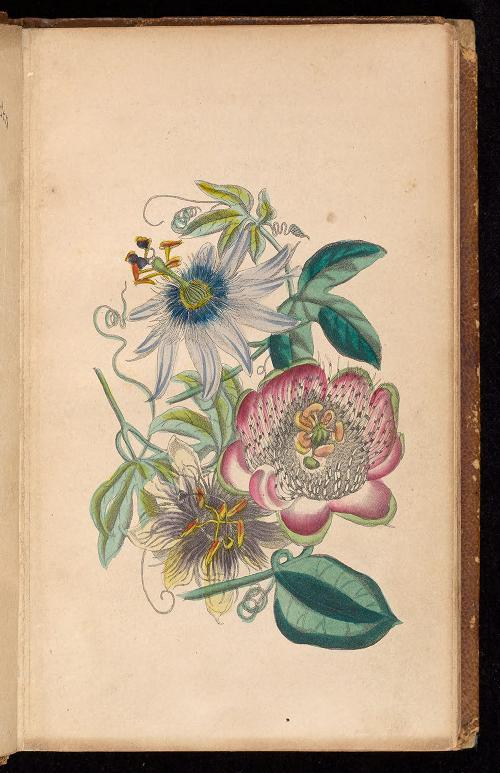

DPA’s Humanities Collections and Reference Resource program has supported preservation and access for collections that tell us about the land and humans’ interactions with it. In recent years, we have funded the digitization of the papers of nineteenth-century naturalist John Torrey at the New York Botanical Garden, the conservation and digitization of rare botanical books at the Chicago Botanical Garden, and the processing of the papers of contemporary landscape architect and urban planner Walter Hood at University of California-Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design.

We are not new to this understanding of environmentally focused collections as paramount to humanist inquiry, but the current moment increases our attention to them. We are keenly aware of how collections of books, manuscripts, and specimens of “natural philosophy” were perceived in the early modern period, and for this reason, we maintain that such collections must be understood in the context in which they were created. Records of the natural world complement, but also complicate, the written historical record by challenging anthropocentric constructions of the past. If you are working to make environmentally focused collections more available for humanities research, education, or public programs, please consider the ways NEH might support your efforts.

If you have ideas or questions about such a project, please contact us at @email. Please note that the current deadline for HCRR applications is July 19, 2022, and we are happy to read drafts submitted before June 7, 2022.

1A Sand County Almanac, with Essays on Conservation from Round River (1949): 18.

2Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (1983): 7.

3 “Grounded Histories: Land and Landscapes in Early America.” William and Mary Quarterly 68, no. 4 (October 2011): 514.