Americans were on the move. Clamoring to “see the USA . . .” in their Chevrolet—or Pontiac, or Ford—with their elbows out open windows, maps on front seats, kids romping in the back, they took to the roads.

In the pre-Interstate, Route 66 era, folks who wanted to photograph giant saguaros, or desert trail ride, or day-trip into “Old Mexico,” could head south from 66 on US 89; or travel east or west on US 80, and they’d eventually hit the Old Pueblo—they’d hit Tucson.

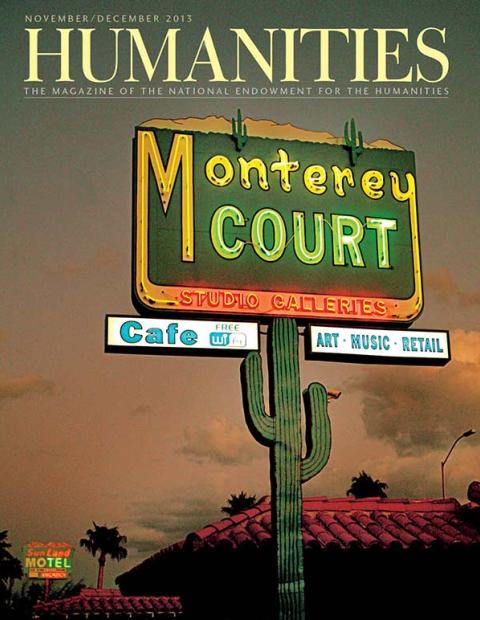

It was a dusty little place in the fifties, but Tucson had a sweet climate and the lure of the West. Where the highways traversed the city, mom and pop motor hotels proliferated. Names like The Desert Edge, La Siesta, Coronado, Frontier, Pueblo, Monterey, and Riviera suggested respite, or conquistadors, or cowboys and Indians, or exotic luxury. Featuring swimming pools, air-conditioning (by refrigeration), TVs, they vied with each other to capture travelers’ attention.

And how better to capture attention than with the siren glow of neon?

For decades, then, neon signs beckoned to passersby in Tucson. The glowing gas tubes, introduced in Paris in 1910 and Los Angeles in 1923, landed in Tucson by the thirties. Towering over streets, neon announced businesses, eateries, motels; it took the shape of stars, flames, arrows, palm trees; it represented seemly—and unseemly—enterprises. This was a time of glowing, flashing, unabashedly gaudy exuberance. In the 1950s, neon’s heyday, there were hundreds of signs, says historic preservationist Demion Clinco: They were “ubiquitous in the urban landscape.” But they were destined to fade.

Blame progress, economics, and aesthetics. In 1961, Interstate 10 sliced through the outskirts of the city, overriding Routes 80, 84, and 89, and drying up the travel trade. By the seventies, the “gateway to the city”—Miracle Mile—had turned seedy; its establishments like the No-Tell Motel (an actual hotel), renting rooms by the hour. The oil crisis and cheaper airfare changed travel habits. Plastic, back-lit signs took over the advertising market. And the Tucson City Council enacted a restrictive sign code. Scores of signs that didn’t comply were pulled down and trashed. Others stood to rust for years, their neon tubes shattered.

Recently, however, nostalgia and a taste for Mid-Century Modern have redefined vintage neon signs as folk art. In Tucson, a movement promoting the signage was led by the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation under president Demion Clinco’s leadership. The foundation pressed for a reexamination of the sign code, and, in June 2011, the Tucson City Council approved a code amendment that would exempt historic signs.

With the code exemption under way, the foundation partnered with local Pima Community College, whose downtown campus followed the historic US 80 and US 89. Pima agreed to a public art installation: To place four restored 1950s signs—one sporting goods, one miniature golf, and two motels—on campus along the traditional route.

The project had its challenges. The sports store sign—a simple white cursive “Medina’s”—was rescued by the foundation when its building was demolished. It came with the roof attached. Magic Carpet Golf—a back-lit genie riding an undulating, blinking neon “Magic Carpet” over a gigantic golf tee—was so heavy even the most ardent preservationist couldn’t justify restoring it to its original state. The wildly colorful, palm tree-draped “Tropicana Motor Hotel” had to be extracted from demolition rubble in pieces.

The story about the 1951 “Canyon State Motor Lodge/Arizonan Motel”—which is shaped like the state of Arizona —is that one day, back in 2010, it just went missing: there one day; gone the next. Turns out, the motel’s owner felled the sign (“like a tree,” says Clinco), notching it with a blowtorch, and dragging it away with a backhoe. The foundation salvaged it, but if you look closely, you can still see the buckled steel.

Hoping the code change, the Pima College installation, and the refurbishing and repurposing of other classic signs in Tucson would spark the public’s interest, the foundation developed a driving tour of classic Tucson neon signs. It inventoried about one hundred signs, and designated thirty as historic on the old US 80 and 89 routes. Then, with a grant from the Arizona Humanities Council, the group printed a full-color guide, Tucson, the Neon Pueblo: A Guide to Tucson’s Midcentury Vintage Advertising, also available online.

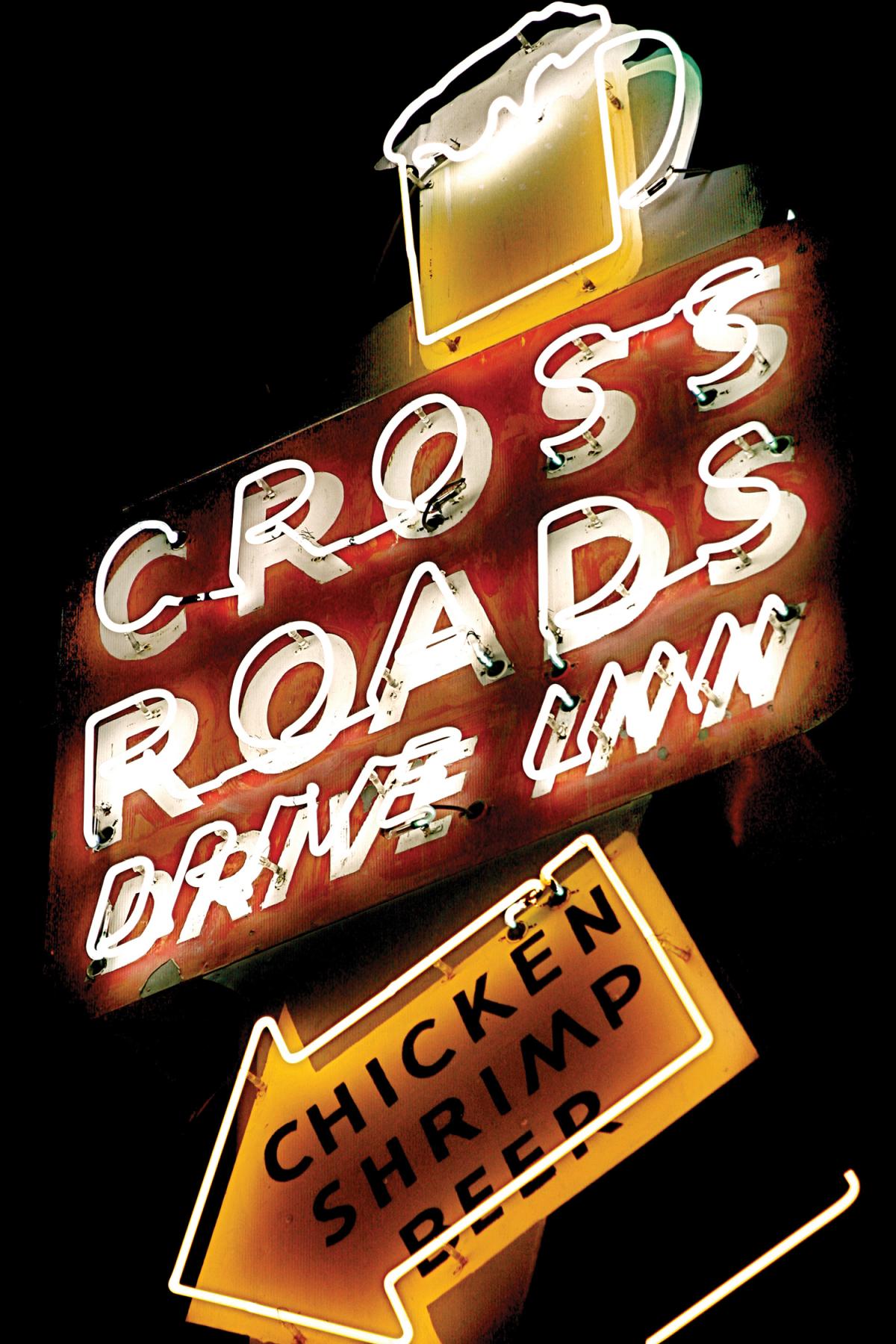

Starting about four miles northwest of downtown with a haunting Georgia O’Keeffe painting on the 1952 Ghost Ranch Lodge sign (its famous cow skull design had been a wedding gift to the owners), the tour heads south toward the iconic 1950s Tucson Inn, with its six pole-mounted letters fanning high into the air; it passes artist Dirk Arnold’s contemporary neon saguaro and the Pima College installations. Carrying on southward, toward downtown through funky Fourth Avenue, it goes by the 1939 Caruso Restaurant’s portly chef repeatedly spooning up pasta; downtown, it goes under a bathing beauty who’s been teetering on a diving board since 1955. South of downtown, it passes the art deco-themed T and T Market (still a “carnicería”), the 1951 yellow-and-white beer mug of the Cross Roads Drive Inn, and finishes at the Western Motel, where a cowboy and a steer have been caught in a perpetual flying chase since the forties.

The project has been a labor of love. Jude Cook, whose sign company has done many of the restorations, moistens with his thumb a frame to show a visitor how much paint has been sanded to find the original color. To replicate originals, workers search for photos and postcards; they scour for glass shards, look for “ghost” letters. Clearly a fan, Cook says older signs have the “character, the feel” new ones can’t touch. And aluminum can’t compete with steel; or backlit plastic with neon in glass.

The natural color of electrified neon gas—as Georges Claude first encased, excited, and exhibited it back in 1910—is a rich orangey red. That’s not unlike the color of Tucson’s hallmark sunsets. With that in mind, a romantic among us might be tempted to follow the driving route at dusk, going from the Southside north—back through downtown, along Fourth Avenue, to the Pima College strip, there to park and watch as the western horizon goes from yellow to orange-red, to deep blue, to black. And then to neon.