American Antiquarian Society

National Humanities Medal

2013

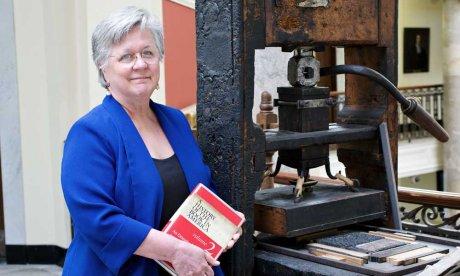

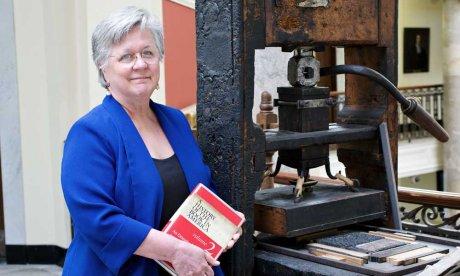

Ellen S. Dunlap, president of the American Antiquarian Society, stands before “Old Number 1,” the press on which Isaiah Thomas, AAS’s founder, learned to print as an apprentice.

Cade Overton / American Antiquarian Society

Ellen S. Dunlap, president of the American Antiquarian Society, stands before “Old Number 1,” the press on which Isaiah Thomas, AAS’s founder, learned to print as an apprentice.

Cade Overton / American Antiquarian Society

If anyone can be said to have lived his entire life with ink coursing through his veins, it is Isaiah Thomas (1749–1831), the leading printer and publisher of his generation, and founder in 1812 of the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts, the city where he made his fortune in the early years of the Republic. Raised in poverty by a mother who was widowed when he was three, and entirely self-taught, Thomas recalled later in life that he learned how to set type as a six-year-old apprentice in the Boston printing shop of Zechariah Fowle before he knew how to read.

Entrepreneurial, ambitious, and a high-spirited patriot to the core, Thomas published one of the feistiest newspapers of the Revolution, the Massachusetts Spy, and built a far-flung empire afterward that included multiple printing operations, a bindery, and a paper mill. A keen student and champion of his craft, Thomas wrote a two-volume history of printing in North America from its beginnings on the continent, all the while gathering a wealth of primary materials that became the seed collection for the first independent research library in the United States, which from the outset was mindfully national in what it set out to acquire.

If there was a particular inspiration to what Isaiah Thomas envisioned, it was his conviction that everything was pretty much in play, so long as it was printed on paper, and so long as it elucidated in some way American history, literature, or culture. While newspapers were central to what Thomas was determined to gather—and there are two million of them now among the holdings, most published before 1876, the society’s cutoff date for inclusion—they represented just a subset of what he insisted would be preserved. Pamphlets, tracts, almanacs, sermons, travel narratives, agricultural reports, handbills, posters, political broadsides, engravings, primers, directories, atlases, sheet music, children’s books, popular entertainments, trade cards, ferry tickets—imprints of all sorts and on a multitude of subjects that today are called “ephemera” were a part of the mix as well, and today share space on twenty-five miles of shelving in the society’s environmentally secure storage vaults.

“What Isaiah Thomas knew, and what he unequivocally said, is that we do not know what those who come after us will need,” is how Ellen S. Dunlap, president of the AAS, describes the mandate she has followed at the helm since assuming direction of the society in 1992. “Isaiah Thomas recognized that it was printing that created and fueled the Revolution. He said that printing was the art by which all others are known. He made it one of his missions in life to document the history of printing in the nation. He was interested in the great and the famous works, and he aggressively went after them, but in his view, the everyday, ordinary things were just as important. That’s really the genius of what he started here.”

At a time when research institutions everywhere are grooming their hard-copy inventories in favor of digitized facsimiles, the AAS continues to seek out and acquire original materials that support its goals. “This institution has always been entrepreneurial, from Isaiah Thomas onward; he and his successors took on big jobs, and that kind of institutional tradition still drives what we do,” Dunlap says. “They all knew that it is the small-town newspaper that tells the story of a town, and so we continue to collect every issue of every small-town newspaper in America that we can find. We have more of anything than everybody else has, because we have stayed focused from the beginning.”

Because everything the AAS does is part of a continuum, the process is unending, Dunlap adds. “We are finishing what our predecessors started eight generations ago. And some of what we are starting now will be finished by the generations that follow us. It’s an accretive process. What we do, essentially, is we get things, and we are very non-discerning when it comes to acquisitions. It’s either an H or a W—either we have it, or we want it.”

Knowing what the society does have, and how it can be most useful to scholars, is the purview of a staff that now numbers sixty professionals, with expertise in a variety of specialties. “I can’t say enough about them,” Dunlap says. “The one point researchers and fellows always make, they all say the exact same thing: ‘Everything I asked for, you found; you showed me things I didn’t even know existed.’”

Arriving in Worcester at a time when the Internet was beginning to flex its muscles in many unprecedented ways, Dunlap has presided over numerous initiatives that have taken full advantage of the new resources, most notably in the preparation of an impeccably detailed bibliographical catalog of early American imprints that is meant to be the final word in the field “whether we own it or not,” and readily available online to scholars everywhere.

“This institution hasn’t really changed so much, but it has definitely evolved,” Dunlap concludes. “All the people who come here kind of become our alumni, too, and that will never change either. The essence of what we do would completely resonate with Isaiah Thomas, of that I have no doubt.”

—Nicholas A. Basbanes