To change the world is the dream of many an ambitious figure, but what about those who want to unchange it? Who dream of the old order that existed before the 1960s, or before World War I, or before the French Revolution?

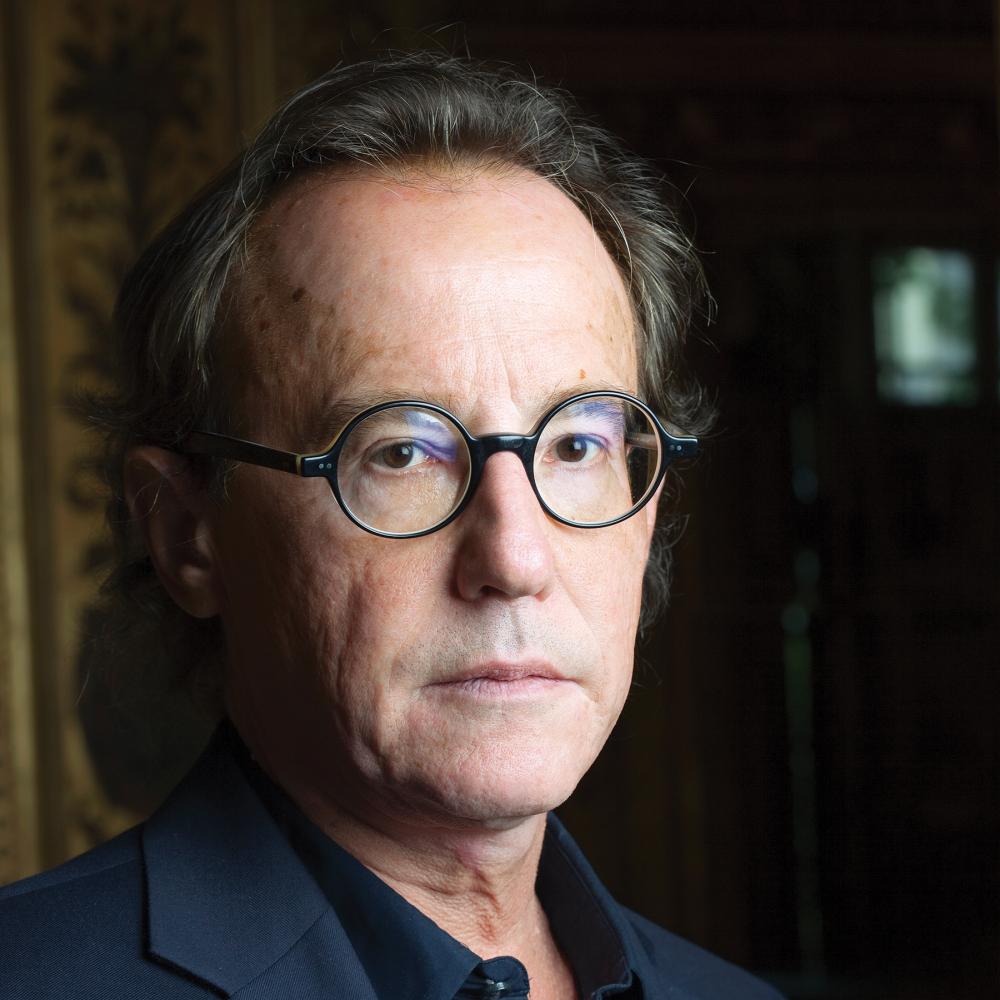

Mark Lilla is a professor of humanities at Columbia University and a contributor to the New York Review of Books. In his new collection of essays, The Shipwrecked Mind: On Political Reaction, he explores the lives and ideas of sundry reactionaries for whom the last revolution “marked the end of a glorious journey, not the beginning of one.” His gallery of backward-looking thinkers stretches from the German-Jewish thinker Franz Rosenzweig to the émigré philosophers Leo Strauss and Eric Voegelin, and all the way to the political Islamists who dream of restoring a caliphate.

In 1992, Lilla received a grant from NEH to support translations of postwar political theory in France for a book he edited called New French Thought. His interest in continental philosophy and the modern era has also resulted in books on Giambattista Vico and the place of the religious imagination in contemporary politics. This fall New York Review Books reissued a prequel to the current volume called The Reckless Mind: Intellectuals in Politics, which is about the dangerous relationship between politics and philosophy as evidenced in the lives of Martin Heidegger, Carl Schmitt, and others.

Recently, HUMANITIES emailed Lilla several questions and he emailed us back several answers.

HUMANITIES: What is the shipwrecked mind? Why is it shipwrecked?

MARK LILLA: One of the most common metaphors for history, and for time itself, is that of a river. Time flows, history has currents, etc. While thinking about this image, it occurred to me that some people believe that time carries us along and all we can do is passively experience the ride. Think of cyclical theories of history or even cosmology: The world runs its course, is destroyed, and is then reborn to travel the cycle again.

Other people, though, have a catastrophic conception of history: The river flows but it may not be heading in the right direction. It might flow into a channel full of shoals or rocks, where a ship can run aground or be shattered. This, I think, is the picture of history that reactionaries have. They believe that some calamitous event has taken place in time, that history has gone off course, and that the kind of society they lived in (or imagined they lived in) has shattered. They find themselves on the shore, looking on as the debris of everything they valued is swept away by the current. The present becomes unbearable, as does the prospect of the future. And so they convince themselves that something radical must be done to either recover or redeem what has been lost.

HUMANITIES: The reactionary belief that something beautiful has been lost to us can be as compelling to the political imagination as its opposite, the revolutionary idea that we might be able to leap out of the present and into a better and more just future. Why then, as you point out, have scholars neglected reaction and the reactionary, in favor of studying revolution and the revolutionary?

LILLA: Because most Western intellectuals since the French Revolution have held some sort of progressive view of history. They have believed that over the course of time things just naturally improve; that was the illusion of the nineteenth century. Or they have believed that forces for good have seized control of history—the workers, the Third World wretched of the earth—and that, however dismal things may now appear, they will eventually triumph. That was the illusion of the twentieth century.

Meanwhile, though, not only were there powerful minds who dissented from these views. Events were also being shaped by forces of resistance that intellectuals, given their assumptions about history, had trouble making sense of. The term “reaction” enters European political thought with Montesquieu, who borrowed it from Newton. Just as actions lead to reactions in the physical world, so, Montesquieu suggested, a similar string of actions and reactions takes place in political life. “Reaction” was an analytical term. During the French Revolution, though, it became a term of abuse applied to those who were deemed as standing in the way of the revolutionary project and the ultimate destiny of mankind. Anyone or anything that didn’t fit got stamped with this label from then on.

Thereafter European history books adopted a romantic, heroic narrative that strung a thread through revolutionary events—1789, 1848, the Paris Commune, 1917—and treated the periods in between as fallow, or as merely preparing for the next advance. Yet, throughout the nineteenth century, European nations were largely being governed by forces hostile to the revolutionary surge. They had their own thinkers and their own dystopian historical narratives. Now that we no longer have confidence in progressive history, or in the forces that claimed to be its avatars, we are finally free to notice and study those who did as much to shape the modern world as revolutionaries have. And continue to do so.

HUMANITIES: You draw an important distinction between the conservative and the reactionary. What is the difference?

LILLA: Conservatives and liberals argue about politics in terms of human nature, and their dispute is about the proper relationship between individuals and societies. Traditionally, liberals begin with individuals who are endowed with certain rights, and think of the legitimacy of political institutions in terms of consent and the protection of those rights. Conservatives begin with societies and the observation that we all come into them as dependents, incurring obligations as we are protected and nurtured by them. Our rights are conventional, not natural, and are not the essence of politics. Traditions and norms are.

The dispute between revolutionaries and reactionaries is not over human nature. It is, as I’ve been suggesting, over the nature and course of history. And so, in many ways, conservatives and reactionaries are adversaries. The conservative believes that change should happen slowly, but that it is inevitable. He might regret what has happened in history, but he is under no illusion that the past can be recovered or recreated; neither does he believe that society should be reconstructed according to some rational plan inspired by the past. The conservative thinks that while societies differ, human nature stays pretty much the same over time and that the problems of politics are perennial. The reactionary thinks that history has changed human nature and that action in history can restore it to what it should be.

HUMANITIES: You describe political Islamism as a reactionary movement. What makes it so?

LILLA: The reactionary who believes that history has gone wildly off course and that the present is unbearable faces a choice when it comes to political action. One option, call it the Ulysses one, is to try to return home, which the reactionary believes is still possible. There are many currents of Islamism, some political and others not, but the most radical ones claim in their literature that Islam ceased to exist after the rule of Muhammad and the four “rightly guided caliphs.” To become Muslim therefore means to become Muslim again, which means overthrowing the current rulers of ostensibly Muslim nations and reimposing sharia law, in the best circumstances under a new caliph.

Another option, call it the Aeneas one, is to recognize that the past is past and cannot be reconstituted—no more than Troy could be after the Trojan War. And so, the essence of the past must be planted in the future, where it will give rise to a new, magnificent, and conquering force that will overcome the corrupt present and create a future as radiant as what once was. That is the spirit of fascism.

HUMANITIES: You have been specializing in a kind of profile essay about political thinkers. They’re heavily biographical and intellectual, using what is, at least to my mind, more of a magazine formula than a book formula. And yet, surprisingly, you apply this genre to some very complicated figures. What does the biographical essay offer you as a writer and historian of ideas that a more academic or analytical style of writing does not?

LILLA: The older I get, the less interested I have become in problems of pure political theory, and the more absorbed I now am in questions of political psychology. The distinction between them did not always exist. Plato, Aristotle, Montaigne, Hobbes, Rousseau, and Tocqueville were master psychologists who understood that politics is the arena in which principles confront the human passions, where they reshape each other. In the nineteenth century this approach to politics was eclipsed by historicism, and in the twentieth by moral philosophy.

The profile form gives me the chance to explore the interaction between political ideas and the passions in intellectuals themselves. And there is, in my experience, always a connection—and in most cases, it is the key to understanding both the thinker and the likely consequences of applying his ideas to politics. One learns infinitely more about politics by reading Isaiah Berlin than by reading John Rawls. I’d like to think that in my own modest way I’m keeping Berlin’s tradition alive.