Tune In Tuesdays: Silent Film Era Collection

Portrait, Clara Bow, undated. Gift of Frederika Tuttle Hastings and Helen Tuttle Votichenko.

Courtesy of the Museum of the Moving Image, New York, NY.

Portrait, Clara Bow, undated. Gift of Frederika Tuttle Hastings and Helen Tuttle Votichenko.

Courtesy of the Museum of the Moving Image, New York, NY.

This post is part of our “Tune In Tuesdays” series, highlighting some of the projects NEH has supported to preserve and provide access to rich audiovisual materials important to humanities research, teaching, and the public interest. We are also proud to announce a NEH symposium on audiovisual preservation to be held on September 30, 2016, in Washington, D.C. Information about the event, called Play/back, can be found here.

Only a fraction of American silent films produced exists today. According to experts, eighty percent have been lost to degradation, fire, or intentional destruction. The silent film era, so important to entertainment and popular culture, began in 1894 when New Yorkers lined up at the first Kinetiscope parlor (with technology from Edison Labs) to see a show for 25 cents. Nickelodeons and small storefront theaters were soon ubiquitous, and studios built massive theaters to show ever more elaborate productions. Finally, after the success of the film The Jazz Singer in 1927, silent films gave way to “talkies.”

But with so many of the silent films now lost, how can we understand this pop culture phenomenon? What were those early movies like? Since many are gone forever, it’s all the more important to preserve and look to the material culture of the period to tell the story of American filmaking.

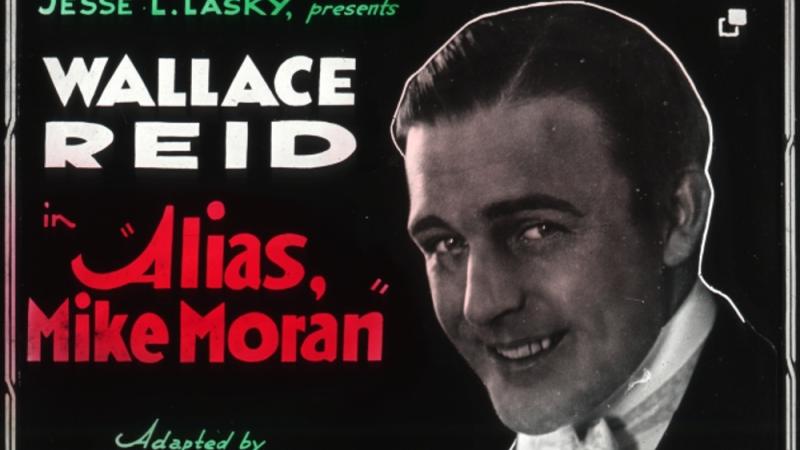

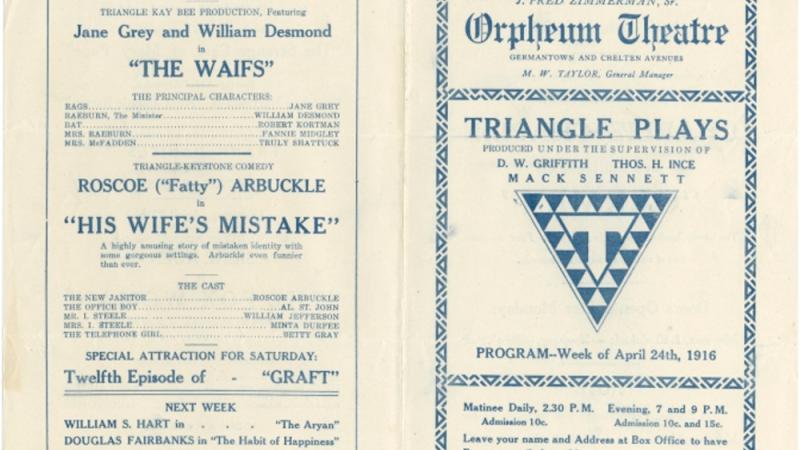

Supported by a 2008 Humanities Collections and Reference Resources grant, the Museum of the Moving Image, located in New York City, has digitized thousands of artifacts dating from 1894 to 1931 related to silent films. Its collections depict early moviegoing practices by displaying, for example, the technical apparatus used to make and show films, portraits and stills of movie stars and sets, photos of studios and theaters, and marketing creations like lobby cards, press books, posters, and more. For example, images of early movie-making equipment include this 1923 Bell & Howell 16mm motion picture camera. One of the era’s many “preview slides” (also called lantern slides) advertising coming attractions depicts the 1917 film Cleopatra.

For early examples of merchandising, check out the board games Polly Pickles: The Great Movie Game from 1921 or Movie-Land Keeno, featuring Charlie Chaplin, Clara Bow, and Douglas Fairbanks, from 1929. A paper doll of Charlie Chaplin depicts his character in “The Tramp,” and this decorative tin shows the silent film actress Bebe Daniels. There’s also a Rudolph Valentino cigar box. An advertisement for the 1923 booklet Can Anything Good Come Out of Hollywood? promises an examination of the “sensational fiction stories” produced by the “world-famous California motion picture colony.” The collection also contains more collecting cards, souvenir spoons, and tie-in books than you can count, featuring the greatest stars and productions, both remembered and forgotten, of the day. In addition to browsing the online collections, you can learn more about the silent film era or explore spotlights on Paramount at the Astoria Studio, Race Movies, and Richard Hoffman’s Collection of early fan memorabilia. Check it out today!