Spring Break in Florida: Vizcaya Museum and Gardens

View of the Gardens

Photograph by Bill Sumner, 2012

View of the Gardens

Photograph by Bill Sumner, 2012

For those of us who dream of South Florida in early spring, the home of American businessman James Deering (1859–1925) offers us an interesting lure for some arm-chair traveling. Miami’s Vizcaya Museums and Gardens is a National Historic Landmark home that was planned and built between 1910 and 1922 on Biscayne Bay. Its owner, James Deering, was the son of William Deering, founder of the Deering Harvester Company, a farm equipment manufacturer based in Chicago. James worked for his father’s firm, which was renamed International Harvester in 1902 and which was, for a time, the largest producer of agricultural machinery in the nation.

As a retired millionaire, James Deering imagined a vacation home planned around the idea of an old Italian villa. With the help of an artistic director, Paul Chalfin, Deering purchased many European antiques and designed an estate to display them. Some 25 years after Deering’s death, Vizcaya was conveyed to Miami-Dade County, which opened the estate to the public in 1953. The museum now features the Main House with 34 decorated rooms showcasing over 2,500 art objects and furnishings; ten acres of European-inspired formal gardens; a significant orchid collection totaling 2,000 specimens; and 25 acres of endangered primary growth forests.

In 2014, NEH awarded Vizcaya Museum and Gardens a Preservation Assistance Grant to purchase environmental monitoring equipment to help the staff better understand the conditions affecting their collections, which represent many cultures and periods of art—ancient Roman sculptures, Renaissance tapestries and architectural elements, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century statues and garden decorations, Chinese ceramics, Rococo and Neoclassical furniture, and early twentieth-century sculptures and paintings. The museum also holds nearly 1,000 linear feet of archival collections including photographs, correspondence, blueprints, and financial records related to the construction and management of the estate.

Caring for such a broad range of material types is no small task, and we are fortunate that the staff of Vizcaya Museum and Gardens has kept us abreast of their efforts. We’ve had a chance to talk with Curator Gina Wouters, and she agreed to answer a few questions about the museum’s work. Ms. Wouters is part of Vizcaya’s Collections and Curatorial Affairs Division, which is responsible for management, research, conservation, and display of the museum’s historic art collections.

What are some of the unique challenges of caring for the collection in a historic home in Florida?

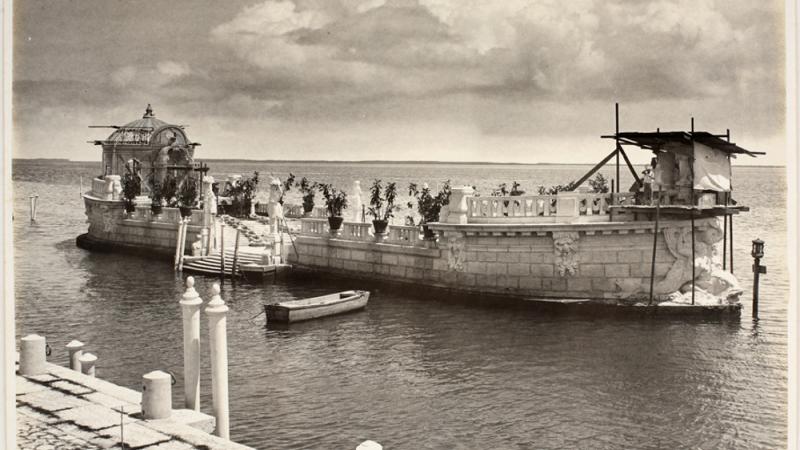

I think undoubtedly the natural environment is the biggest challenge. Since Vizcaya’s creation in the 1910s, hurricanes have been a major and constant threat as well as the most impactful cause of damage to the collection. Additionally, the Bayfront location with persistent direct exposure to the marine environment has certainly taken a toll on works in this area. Native coral stone was the material of choice for architectural elements and select sculptural work and the permeability of the stone and its sustained exposure to the Florida climate has left us in many instances with little detail to discern.

What is one of Vizcaya’s current conservation priorities?

One of the priority institutional projects at the moment is the treatment of our Robert Winthrop Chanler swimming pool ceiling. Vizcaya organized a national symposium on the artist in 2014, and we are co-publishing a book on the artist with Monacelli Press. The book, Robert Winthrop Chanler: Discovering the Fantastic, will be released in April 2016.

Chanler is an enigmatic figure who was incredibly prolific and accomplished during his lifetime (1872-1930), but until recently was entirely missing from the American art historical canon. We have one of two of his architectural spaces that are open to the public. The other is at Coe Hall on Long Island. The remaining extant works, both immersive spaces and movable screens, are in private hands or private clubs mostly in New York.

We’ve been working with diverse teams of conservators to think about the prognosis of the space. Chanler didn’t make it easy and created the underwater fantasy scene out of painted plaster directly above a pool and feet from the bay. To say the least, there were problems from the start. So now we are weighing in artistic intent, museum interpretation, visitor access, preservation ethics, significance of the space as a whole, and more factors to plan for the next hundred years. The end of 2016 will mark our centennial, as well as the centennial of the ceiling installation, and we are hoping to be underway with treatment.

Of Vizcaya’s collections of art, furniture, and other objects, what item do you most wish the world could see?

Vizcaya is a very complicated place because its makers, owner James Deering and artistic director Paul Chalfin wished to create an aesthetic that evoked the passage of time and wanted to present the house as if it had stood on the edge of Biscayne Bay for centuries. Their design intent was so successful that our general visitors walk away not fully understanding the era in which it was created, the early twentieth century. For this reason, I would like the world to see the work that Deering commissioned from contemporary artists, because this is one of the few moments where the site reveals that it was a product of its time. Although the majority are visible, such as the Barge statuary by A. Stirling Calder, the pool ceiling and Vizcayan Bay screen by Robert Winthrop Chanler, or the native coral stone peacocks by Gaston Lachaise (currently in storage), they are not necessarily called out for the visitor to fully consider. Deering was collecting European architectural elements and objects d’art but at the same time he was engaging progressive artists to add their own layer to the overall design of Vizcaya. This truly demonstrates the hybridity of the site.

We thank Gina Wouters for her time and insight on this unique historic home, as well as the staff of Vizcaya Museum and Gardens for the wealth of information presented on their Web site, vizcaya.org, from which much of this article was gathered.