Celebrating Black History Month Part III: Documenting the Civil Rights Era—From Famous Figures to Everyday Life

The DeArdis and Annie M. Belton Collection

Courtesy of Southern University at Shreveport

The DeArdis and Annie M. Belton Collection

Courtesy of Southern University at Shreveport

Bus boycotts, protest marches, and school integration are vibrant symbols of the civil rights movement. Yet interest in the civil rights era has extended beyond these iconic images to broader questions. What was everyday life like in African American communities across the United States? How were the messages of civil rights leaders formed, and how did they reach citizens? What did local activists do during the civil rights era? NEH grants have recently supported efforts to preserve and make available important materials from this period, ranging from spiritual influences on civil rights movement leaders to popular culture and community life. The teachings of Dr. Martin Luther King’s “spiritual godfather,” a popular Detroit television program for African Americans, photographs printed in the nation’s preeminent black newspaper, and other collections all contribute to a richer view of the civil rights era, popular culture, and African American life.

The Civil Rights Movement and Beyond

From the Montgomery bus boycott to lunch counter sit-ins, Dr. Martin Luther King and civil rights movement activists were well known for practicing nonviolent protest to drive social change. Less familiar is the influence of Dr. Howard Thurman—sometimes hailed as the “spiritual godfather” of the civil rights movement—on King’s philosophy of non-violence. A theologian and educator, Thurman had been a frequent visitor to the King household, and advised the civil rights leader throughout his life. Thurman was the first African American leader to meet Mohandas K. Gandhi, in 1935, when he traveled to India as chairman of a Pilgrimage of Friendship. He was enthralled by his conversations with Gandhi about nonviolence, and quickly shared these ideas with the leaders of the American civil rights movement. His wife Sue Bailey Thurman, who also made the trip, supported her husband’s career and was a force for change in her own right. She founded the Aframerican Women’s Journal and organized the Museum of Afro American History in Boston. With the support of an NEH Humanities Collections and Reference Resources grant, Boston University’s Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center is now digitizing and making available the Thurman archival collections. Users will be able to examine Thurman’s papers, listen to recordings of most of his lectures, classes, sermons, and speeches, and explore both the Thurmans’ influence on the civil rights movement and their efforts at interracial, interdenominational worship.

On a more local level, materials on activists and professionals allow glimpses into African American life beyond the familiar locations of protest. The history of the civil rights era extends far beyond the organized protests and national movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Black community organization and local activities formed a precedent and a base for later civil rights activities on a national scale. In addition, understanding local community life contributes to broader knowledge of the 20th-century history of African American life. NEH awarded a Preservation Assistance Grant to the Southern University at Shreveport for a comprehensive assessment for proper long-term preservation of its Black Ethnic Archives. These collections, which focus on Louisiana history, include the complete run of the Shreveport Sun, the oldest African American newspaper in Louisiana (1927-present). The collections also include materials on notable African Americans in Shreveport, illuminating lives that included both professional and community activities. The papers of local activists, who worked with national leaders such as Dr. King to rally local support, provide tremendous insights into the grassroots elements of the civil rights movement. Both the Sun archives and the archival collections also round out the picture of everyday life and community activity during the civil rights era and beyond.

Popular Culture and African American History

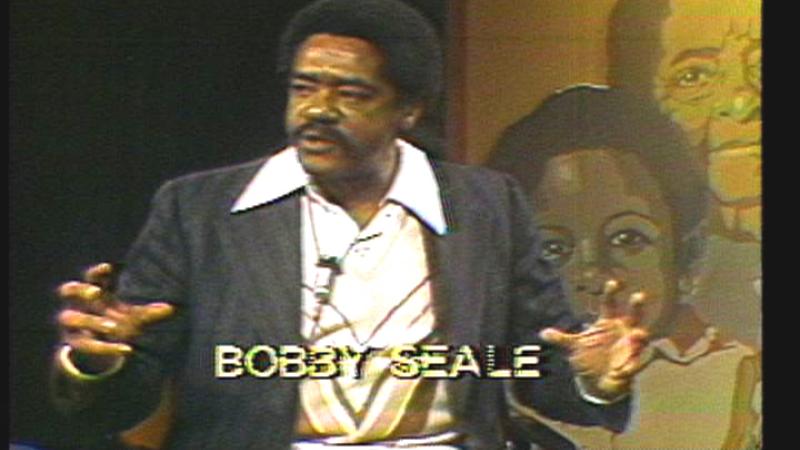

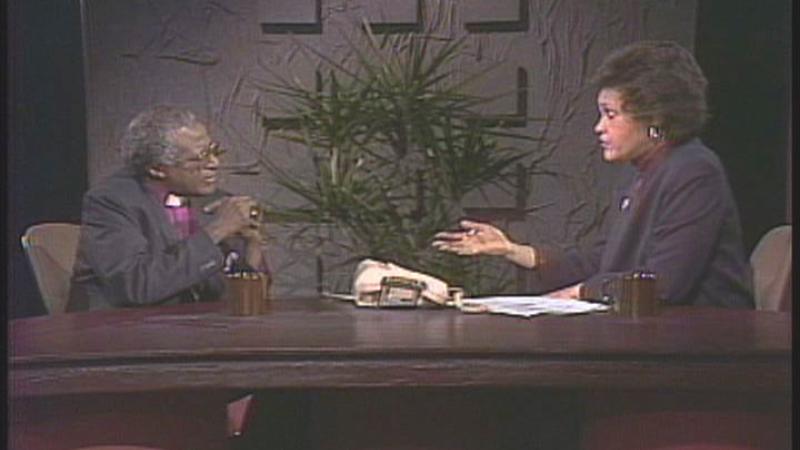

Community activity and concerns of African Americans of a later era are represented by the long-running Detroit Public Television series American Black Journal. The program, which originally went on the air in 1968 under the title Colored People’s Time, was a televised public forum for black citizens. The program included interviews, roundtable discussions, reports, and artistic performances. Detroit was the city with the third largest black population at the time, and the show documented both local and national issues from an African American perspective. Michigan State University’s MATRIX: Center for Humane Arts, Letters & Social Sciences Online and MSU Libraries and Special Collections are partnering with Detroit Public Television and the Charles H. Wright Museum of African-American History to provide streaming video of American Black Journal shows from 1968 to-1990. Once the project is complete, users will be able to explore themes both within and beyond the civil rights movement, including work in the automobile industry, urban civil disturbances, African American political leaders, the development of Motown music, and the emergence of rap.

Everyday Life in African American Communities

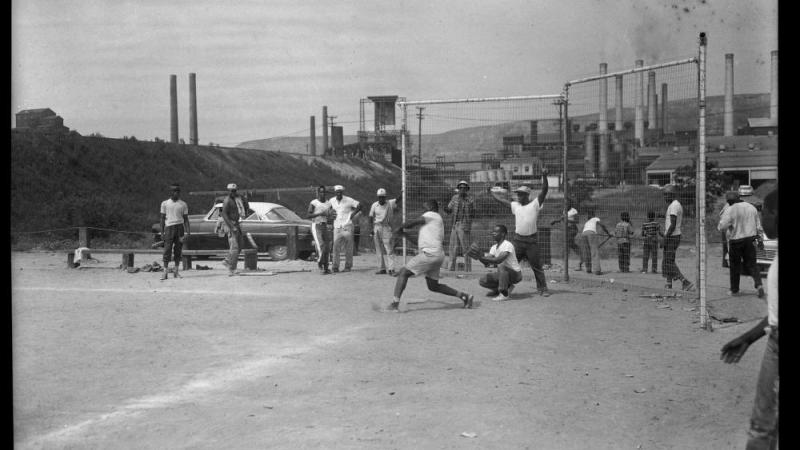

Photographic representations of African American communities tie together civil rights movement activities and ordinary life. Images of the people who lived these stories bring to life the historical themes of segregation, migration, and work, enabling us to imagine their experiences more fully. The treasure trove of the Charles “Teenie” Harris photograph collection is one example of the power of these photographs to present a broad yet nuanced view of that community life. Harris was a freelancer and staff photographer for the Pittsburgh Courier, the highest circulating minority newspaper in the country for thirty years, and he produced over 80,000 images documenting African American daily life in Pittsburgh. Harris’s photographs illustrate the lived realities of ordinary Americans. Among other features, the collection helps to illuminate the realities of segregation, the Great Migration of African Americans from the South, and the experiences of African American workers in Pittsburgh’s iron and steel mills. Two NEH grants supported the efforts of the Carnegie Museum of Art to make over 50,000 of these images available on the Web.

Like the Harris collection, the collection of rare Goodridge Brothers photographs provides unique insights into African American life. Glenalvin Goodridge, one of only a handful of African-Americans involved in photography before 1850, founded the Goodridge Brothers Studio, and his brothers continued his preeminent photographic work well into the 20th century. Photographs include images of Michigan industry (including lumbering and automotive), civic events, local institutions, and community life. An NEH Preservation Assistance Grant was awarded to the Public Libraries of Saginaw, in cooperation with the Historical Society of Saginaw, to support an assessment of the preservation needs of the Goodrich Brothers photographs. Resources like the Harris and Goodridge photography collections are casting new light on the “long civil rights movement” and everyday life for African Americans around the country in the 19th and 20th centuries. These projects illuminate the historical roots of the civil rights movement, as well as the experience of African Americans throughout this tumultuous era.