Lots of small New England towns have quirky claims to fame, but a historical rumor often cited by residents of Springfield, Vermont, is especially intriguing: During World War II, they say, this town of fewer than ten thousand people was number seven on Adolf Hitler’s list of American cities to bomb.

True or not, the rumor references the unique history of this stretch of the Connecticut River Valley. In the latter half of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth, the noisy, shuddering workshops along the river were the nurseries for a new kind of manufacturing: the production of machine tools. Machine tools make highly specialized and identical parts for guns, consumer products, and auto, train, and airplane components, parts that can be interchanged and pro-duced with speed and accuracy.

While Springfield came to be strongly associated with the machine tool industry, much of the technology was conceived about twenty miles upriver in the town of Windsor, Vermont, where this often overlooked piece of history is celebrated at the American Precision Museum.

The museum, housed in an old brick factory building that served at various times as a textile mill, armory, sewing-machine factory, and machine tool shop, is perched atop the rushing Mill Brook and celebrates Windsor’s important role in the history of American manufacturing and technological innovation.

One of the first places where machine tools were created and used, Windsor is an important part of the origin story for what came to be known as the American system of manufacturing. This was a new way of manufacturing using precisely engineered and produced parts that could be easily interchanged. The technology spread out from Windsor to the rest of New England, the United States, and across the world.

A permanent exhibition at the American Precision Museum called “Shaping America”guides visitors through the development of American manufacturing, beginning with this iconic building. On the cavernous shop floor the early history of the Windsor factory is related. The United States Army required large quantities of rifles, helping to give rise to the initial spark of ingenuity in Windsor. Gunmakers Richard Lawrence and Nicanor Kendall partnered to produce high-quality firearms and, with the help of a businessman named Samuel Robbins, in 1844 signed a government contract to produce ten thousand service rifles.

To make good on its contract, the Robbins & Lawrence Armory (Robbins eventually bought out Nicanor Kendall) designed a new kind of factory floor and, most importantly, specialized machines that could make identical and highly accurate parts for the rifles.

In 1851, Robbins and Lawrence traveled to London to show their rifles at the storied Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, better known as the Crystal Palace Exhibition. The Robbins & Lawrence rifles won a medal and prompted the British government, soon embroiled in the Crimean War, to send a team to the factory on Mill Brook. This was followed by an order for twenty-five-thousand Windsor-made rifles, as well as versions of the machines on which their parts had been manufactured.

The benefits were obvious to the British—if a part broke in the field, it could be easily and quickly switched out for another one. They wanted the Robbins & Lawrence rifles, and they wanted to be able to make rifles the same way and in large numbers. The system of manufacturing perfected in Windsor was exported across the Atlantic Ocean.

Rifles continued to be made at the factory in Windsor after the end of the Crimean War, while the nearby Sharps factory switched to sewing machines and other consumer products. The machines that had made inter-changeable parts for rifles could be easily modified to make interchangeable spindles, wheels, and feet.

Then came the Civil War.

By April 12, 1861, when Confederate soldiers opened fire on Fort Sumter, the factory in Windsor had been bought and renamed Lamson, Goodnow and Yale. Partner Ebenezer Lamson traveled to the nation’s capital and signed a contract to produce rifles for the Union Army. By 1862, the factory was once again churning out weapons of war, making three hundred, and eventually one thousand, rifles a week. Even more importantly, it provided the machine tools that other factories could use to produce arms and ammunition.

In all, 1.5 million rifles—and countless other weapons—would be manufactured in the North during the war. Such volume was made possible by the machine tool technology on display at the old brick factory building in Windsor.

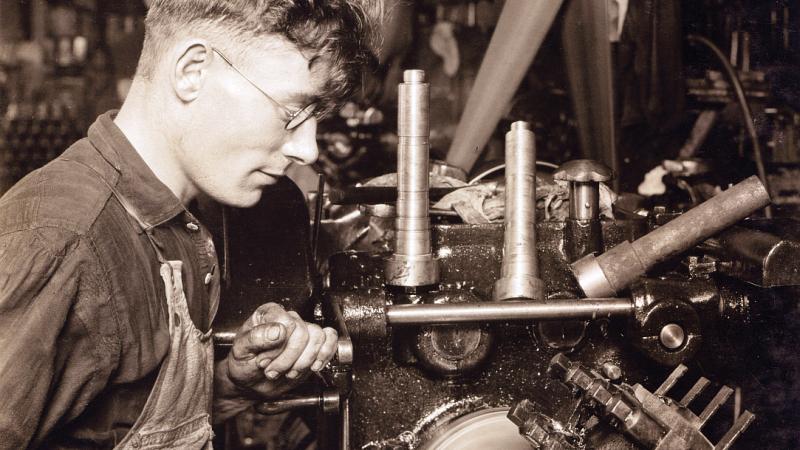

The “Shaping America” exhibit at the Precision Museum displays the actual machines on which the interchangeable rifle and sewing–machine parts were made, giving tangible form to the work of the craftsmen and engineers who innovated in the building. There are contraptions called gunstock lathes, engine lathes, turret lathes, milling machines, and cutting machines. The machines are intricately designed; a faint smell of metal and oil lingers in the air.

In the section devoted to the early history of manufacturing, you encounter a huge gunstock lathe, made in Chicopee, Massachusetts, in 1857, and an early example of a duplicating or copy lathe. Duplicating lathes use a metal model and a stylus and cutters to reproduce the shape of the model in wood. The machine allowed the Robbins & Lawrence Armory to turn out identical wooden gunstocks.

As you wind your way around the factory floor and learn about the different manufacturing companies that inhabited the buildings, you can see more examples of the machines that shop employees used. Turret lathes allowed machinists to attach different tools to the lathe, making it possible for the same machine to perform several consecutive manufacturing steps and saving the operator from having to switch machines. Drills and cutting machines helped make parts for a variety of products.

Surrounded by so many metal machines, it’s easy to forget that there were human beings behind them, designing them and then operating them on the shop floors. In fact, many of the machinists who learned their craft at shops in Windsor went on to open their own machine tool companies in Windsor, elsewhere in Vermont, in Massachusetts, and other parts of the country. Today, a drive down the main drag in Springfield, Vermont, takes you past huge former machine tool factories with names like the Fellows Gear Shaper Company and the Bryant Chucking Grinder Company.

At the Precision Museum, a flat turret lathe designed by James Hartness of Springfield helps visitors make the transition from the era of armaments manufacturing to the age of consumer manufacturing. The flat turret lathes became important to the burgeoning auto industry, and the machine tools would help make possible the mass production of everything from toothbrushes to toys.

In 1889, Hartness, who was born in Schenectady, New York, was hired as superintendent at Jones and Lamson, now in Springfield, and designed the flat turret lathe that would revive the company’s fortunes. An amateur astronomer who encouraged people to build their own telescopes, he became a promoter of aviation as well. Starting in 1921, he served one term as the fifty-eighth governor of Vermont.

During World War I, Windsor and the Connecticut River Valley found themselves exporting essential technology once again. The Windsor Machine Company—which moved into the Mill Brook building after Jones and Lamson moved to Springfield—shipped lathes that were used to make shells for Britain and France and ramped up production of machine tools for armories once America entered the war.

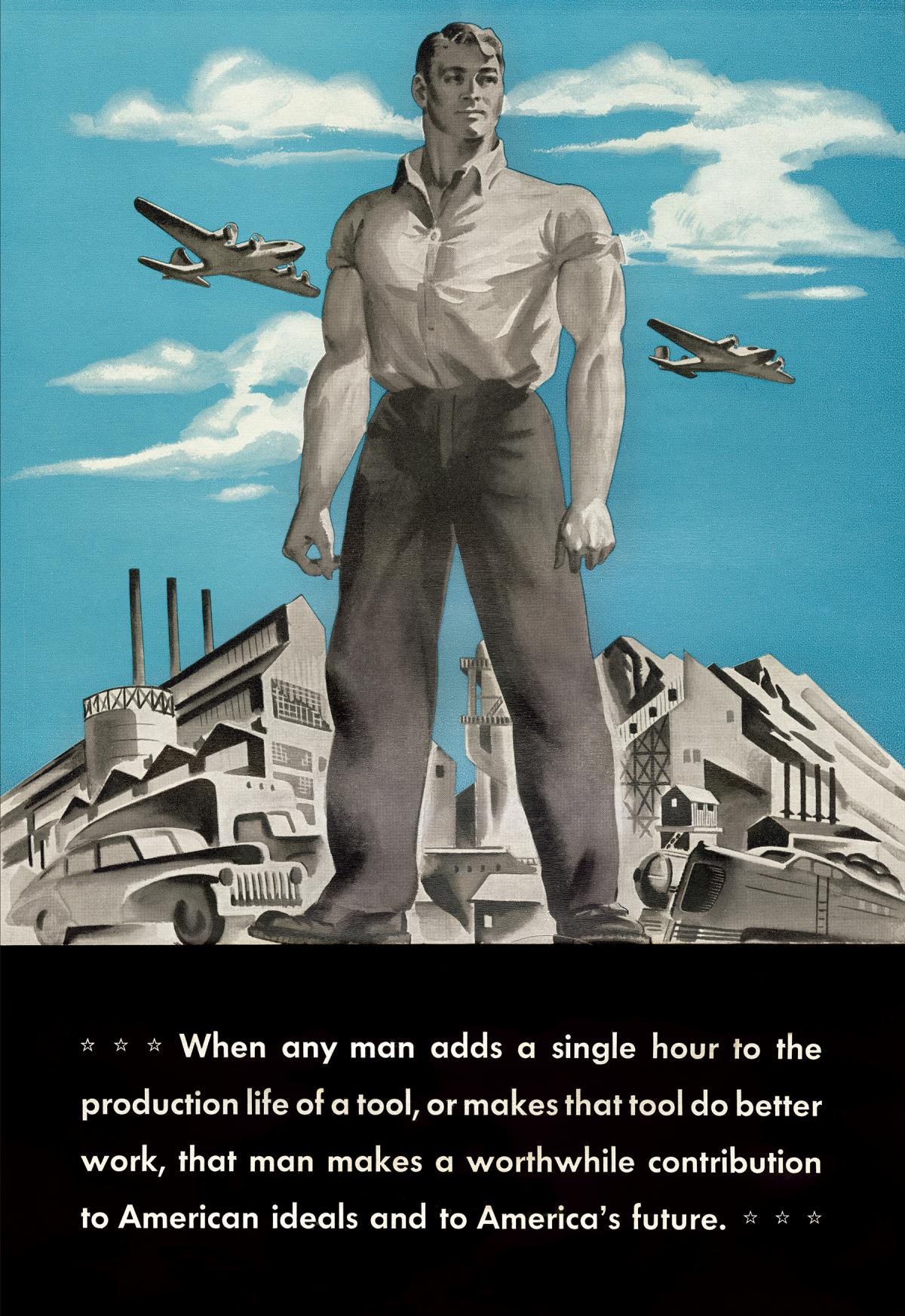

During World War II, the factories and machine shops in Springfield would become essential to the war effort, perhaps putting the small Vermont town on Hitler’s list of targets. The exhibit contains posters with slogans like “You Make it Right. They’ll Make it Fight,” connecting the work of machinists on the home front to the success of soldiers in combat. In 1941 and 1942, American machine tool shops provided about three hundred thousand machines to the war effort. Incredibly, about thirty thousand of those were made in Springfield. Factories ran through the night to meet their production quotas.

As you wander through the exhibit, you can catch views of Mill Brook outside the windows, the rushing water a reminder of the building’s earlier incarnation as a textile mill. Overhead, the belts that powered the machines can be turned on to approximate how noisy the shop floor would have been when all of the machine tools were operating. Videos show how the machines work and give visitors a sense of what it would have been like to run them.

Early machine tools developed in Windsor and then in Springfield led to innovations in automaking and aerospace engineering that would place America at the forefront of manufacturing in the twentieth century.

Making that connection for visitors was something that the museum had been wanting to do for many years, according to executive director Ann Lawless. It had long housed the machines, collected from shops around the region, and traveling exhibits, but there wasn’t a permanent exhibit to interpret the manufacturing history represented by the building.

“Shaping America” became a way for the museum “to link together these machines and the people behind the machines,” says Lawless. “Our themes are the nature of innovation, the role of craftsmanship and skill, and the role of precision manufacturing, which became the backbone of American industrial power.”

One of the interpretive challenges has been to explain manufacturing to visitors who might not know a lathe from a drill. “For some visitors, they appreciate American history and they can connect there. Others can connect through consumer culture and the things they buy,” says Lawless, who points out that this was the same challenge that inspired American Precision Museum founder Edwin A. Battison.

Battison grew up in Windsor and worked at machine tool shops in Windsor and Springfield, eventually going to work at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., as the curator of clocks and watches and then as curator of mechanical engineering. In 1966, near the end of his career at the Smithsonian, Battison arranged for the purchase of the Robbins & Lawrence Armory building for use as a museum and began building the collection of original machine tools. He served as director of the museum until 1991, overseeing the American Precision Museum as it became a destination for historians of American manufacturing and the machine tool industry.

Other than history and cultural heritage buffs, the museum’s audience tends to consist of machinists and firearms collectors. “We also have a lot of men visit whose fathers worked in the shops, and they heard many stories about the machines and they want to see them,” says Lawless. “And then we have women who weren’t told about their fathers’ careers because they were girls, and now they want to learn.”

“Shaping America” includes audio recordings of interviews with men and women who worked in the machine tool shops in Windsor. These voices add a rich and colorful dimension to the history detailed in the exhibit.

Lawless says that the next step is to get more of the museum’s resources online so that they will be available to historians and machine tool buffs around the country. Another goal is to continue to reach out to the local community and further afield through the museum’s new educational programs.

Scott Davison, the museum’s education director, says that the museum has developed a variety of programs for young people that will teach them about the history of American manufacturing. The museum recently debuted a Junior Apprentice Program, modeled on the Junior Ranger Program at many National Park sites. Young visitors learn about the history of the building on Mill Brook and are encouraged to make observations about how the functions of the building changed over time, to understand the principles behind the water wheels and mills that once supplied power to the building, the tools used to design the marvelous machine tools on display, and the many personalities who spent time in the Robbins & Lawrence factory. After answering questions about the museum and the machine tools on display, kids receive a 3-D printed badge.

New educational initiatives include after-school programs and summer workshops and hands-on activities at the annual Model Engineering Show and Makerspace, sponsored by the museum. The museum also contains a learning lab, for hands-on activities, and a working machine shop, staffed by local high school students who are mentored by employees of area manufacturing companies and museum employees. The shop features drills, cutting machines, and other machine tools, as well as 3-D printers.

With all of the recent attention on STEAM education, it’s a good time to be promoting educational initiatives in the humanities that involve technology and engineering, Davison says. But there are challenges too.

“How do we set ourselves apart and find our niche?” Davison asks. He believes it will be in making the connection for young people between the hulking, old-fashioned-looking machines on the shop floor and the sleek latest-model iPhones in their pockets.

“Look at an iPad. This could not be done by hand. It required a computerized precision tool,” Davison says. “And the evolution of that precision tool is shown here at the museum.”