Sam Phillips opened Sun Records in a tiny rented storefront on Union Avenue in Memphis in 1952 with the slogan, “We Record Anything-Anywhere-Anytime.” For a few dollars, anyone could walk in and make an acetate dub of their choice, usually a song or a special message for a loved one. The following year, a fresh-faced teenager just out of high school named Elvis Presley came in to record a ballad for his mother.

Before Presley’s arrival, according to Peter Guralnick, the musical stage was set for something big to happen. “[Phillips] didn’t believe in luck necessarily, but the moon had to be in the right place, the wind had to be blowing in the right direction. . . . He just hoped he would still be in business when that day finally arrived.” Guralnick is the author of Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘N’ Roll and cocurator of “Flyin’ Saucers Rock & Roll: The Cosmic Genius of Sam Phillips” on display at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville.

Phillips opened his Memphis Recording Studio in 1950 with the goal of recording blues music made by black artists. With no record company, no deals lined up, and no outlets once records were made, it was slow going. To make ends meet, Phillips used portable equipment to record whatever a paying customer wanted as a keepsake. “I didn’t open the studio to record funerals and weddings and school day revues,” said Phillips. “I was looking for a higher ground, for what I knew existed in the soul of mankind. And especially, at that time, the black man’s spirit and his soul.”

Phillips grew up near the Muscle Shoals region of north Alabama, where, as a small child, he farmed fields with his family. He was surrounded by all kinds of music. His mother played folk songs on guitar. He listened to radio broadcasts from the Grand Ole Opry. White and black sharecroppers sang a cappella alongside him. Soulful gospel music reverberated from the local black church.

In 1939, when Phillips was sixteen, he stopped in Memphis on a road trip with his brother. He was immediately enamored by Beale Street, home to an energetic and diverse music scene where yet-to-be blues and jazz legends like Louis Armstrong and B. B. King could be heard. Visiting Memphis had a profound effect on Phillips. Guralnick writes, “For a boy who had never even been as far as Birmingham, Beale Street and the Mississippi River were nothing less than the spelling-out of his dreams and his destiny.”

A couple years later, Phillips began his radio career spinning gospel records. After marrying radio personality Becky Burns, the couple moved a few times until Phillips could no longer resist the pull of Memphis. Phillips said, “My conviction was that the world was missing out on not having heard what I had heard as a child. . . . I said, ‘I’ve just got to open me a little recording studio, where I can at least experiment with [some of] this overlooked humanity.’”

After Phillips’s first few unsuccessful attempts to get black music heard by the world, B. B. King urged him to call nineteen-year-old Ike Turner, a bandleader in nearby Clarksdale, Mississippi. As the group made its way to Memphis, someone dropped the guitar amplifier cracking the speaker cone. At the studio, Phillips put wadded paper in the speaker, creating a distorted sound he found appealing. The sound helped Phillips in 1951 produce “Rocket 88,” considered the first rock ‘n’ roll single, which hit number 1 on Billboard’s rhythm and blues chart and stayed there for weeks. Phillips would later say, “‘Rocket 88’ was the record that really kicked it off for me, as far as broadening the base of the music and opening up wider markets to our local music.”

From 1950 to 1954, Phillips recorded black rhythm and blues artists such as King, Howlin’ Wolf (whom he considered his greatest discovery), Rosco Gordon, James Cotton, and others. Although Sun became a respite for black artists in heavily segregated Memphis, Guralnick says Phillips realized that no matter how big an R&B hit he had, it was never going to sell to a wider audience. “It seemed that for all of the fervor of his belief, for all of the success he had enjoyed, with the Wolf, with “Rocket 88,” and with Little Junior’s Blue Flames, he just couldn’t get himself situated on a solid foundation.”

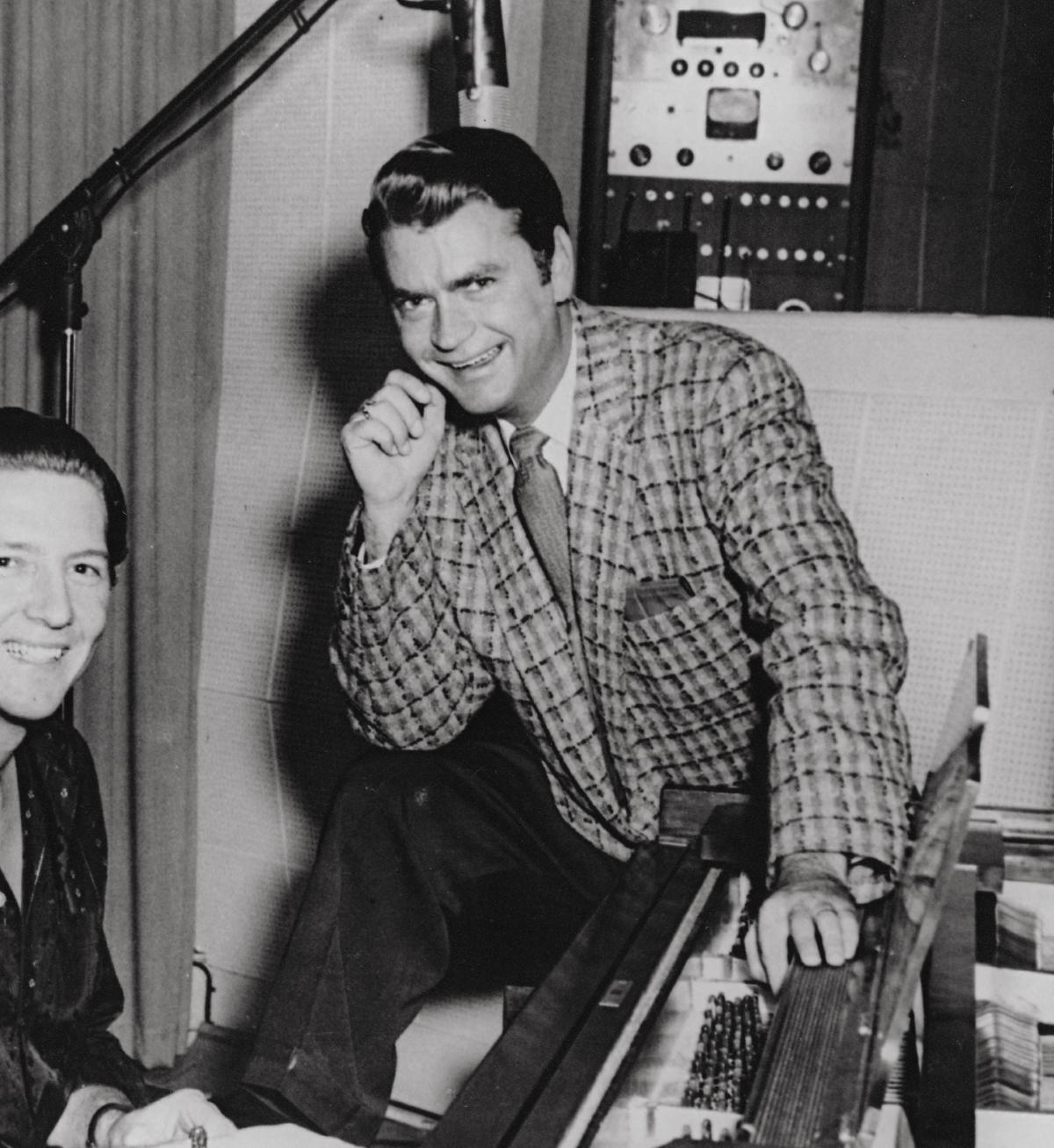

Then walked in Elvis Presley. After a few informal auditions and a session where he sang virtually every pop and country song he knew, Presley spontaneously broke into “That’s All Right” by bluesman Arthur Crudup. Phillips recorded it. That night he told Becky that their lives were about to change. The next day, Phillips gave the record to his friend disc jockey Dewey Phillips (no relation), who played it over and over again and had Presley on his radio show as a guest. A cultural revolution was in the making.

Phillips released five Presley singles over the next year. But, needing capital, he sold Presley’s contract to RCA for $35,000 in November 1955 (which he said he never regretted). At the time, it was the highest price ever paid for a pop artist.

After Presley’s departure, Phillips moved Sun Records forward at breakneck speed. Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, and Jerry Lee Lewis all released big hits in 1956 and 1957. Perkins’s “Blue Suede Shoes” had the rare distinction of climbing the national charts in three genres: pop, country, and R&B.

Presley stayed friends with Phillips. In late 1956, fresh off his performance on The Ed Sullivan Show, he stopped by the Sun studio where an impromptu jam session with Perkins, Cash, and Lewis took place. Dubbed the “Million Dollar Quartet,” the recordings remained unreleased until 1981.

Visitors to the exhibition, funded in part by Humanities Tennessee, can hear early recordings by Presley (including “My Happiness” he recorded for his mother), Lewis’s “Great Balls of Fire,” King’s “She’s Dynamite,” and many more. A video loop shows Howlin’ Wolf growling out “How Many More Years,” with a young Mick Jagger in the audience, Lewis’s manic “Whole Lot of Shakin’ Going On,” and an angelic-looking Johnny Cash donning a bedazzled white suit.

Phillips regretted bailing on black music. Sun artist Rufus Thomas recalled, “Me and Sam Phillips, we were tighter than the nuts on the Brooklyn Bridge, but when Elvis and Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash came along, no more blacks did he pick up at all.” An exhibition label says, “Phillips’s view was that this was the only way to broaden the base for the acceptance of black music, and, ultimately, he felt that it succeeded in doing so.”

Phillips sold the Sun label and all of its master recordings to Nashville’s Shelby Singleton in 1969. For his contributions to American music, Phillips was in the first class of inductees elected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986. In 2001, he was elected to the Country Music Hall of Fame. Phillips died in 2003 in Memphis.

At the end of the exhibition, Phillips’s cultural contributions are noted: “Phillips looked for ‘perfect imperfection’—he encouraged his artists not to smooth out their sound, not to bend their identities to fit a show-business ideal. Thus, on his Sun label, he introduced the world to some of the most primal gut-bucket blues, some of the most frenzied rockabilly, some of the most propulsive rhythm & blues, some of the hardest of hardcore honky-tonk, and some of the most hummable pop music ever committed to tape. The Sun label has come to stand for excellence because Sam Phillips, in his cosmic genius, encouraged nothing less than pure, unmediated originality.”