“We have to find a way to make American history more exciting,” Ron Chernow tells me from his home in Brooklyn.

“It shouldn’t be difficult.”

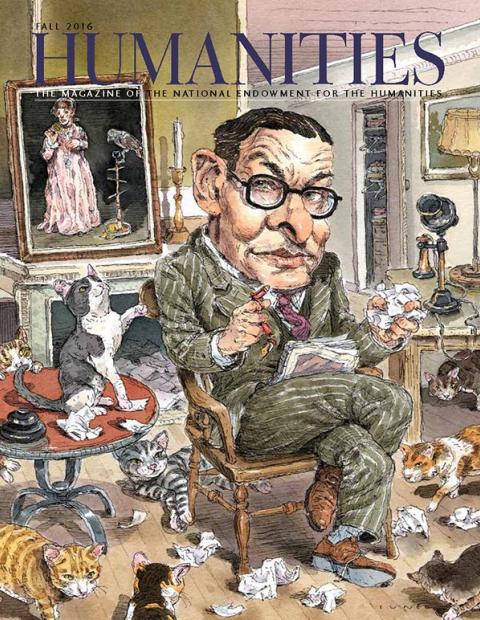

At the very least, Chernow has not found it difficult. He has devoted a career to transforming hefty subjects such as the rise of Wall Street, big business in America, and, more recently, the American founding, into best-sellers that also enjoy enthusiastic approval from critics. In each case, Chernow has employed the writerly device of viewing his theme from the perspective of a pivotal figure or family: for finance, the Morgans, and later the Warburgs; for big business, John D. Rockefeller Sr.; and for the founding, Alexander Hamilton and George Washington.

One of America’s most influential biographers had spent more than a decade working in New York as a journalist and public policy wonk when he conceived of the idea of writing about the rise of American finance—but he found taking the subject head-on as some sort of “history of Wall Street” to be “tedious.” Published in 1990, The House of Morgan earned a National Book Award—no small accomplishment for any history or finance writer, but compounded in Chernow’s case not only because it was his first attempt, but also because he had no formal training in either history or finance.

“Both of my degrees were in English literature, and I never studied history, even though that’s what I ended up writing about,” Chernow says. “I knew from the time I was a freshman in college that I wanted to be a writer, but I imagined that I was going to be a novelist.” He selected his courses of study accordingly. “Even though I wasn’t learning history, I was learning narrative—and narrative is at least as hard to learn as history.”

Skillful storytelling, combined with a taste for great themes and for detailed psychological portraiture, have characterized all of his books since. Lin-Manuel Miranda, the artist who famously turned Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton into one of the most successful musicals in American history, said in 2015 that his collaborator “out-Dickens Dickens” in his portrayal of the future Treasury secretary’s scrappy Caribbean upbringing. Earlier that same year, on the evening of Hamilton’s Broadway opening, Miranda entertained the audience waiting in line outside the Richard Rodgers Theatre by reading aloud the opening paragraphs from a worn paperback copy of Chernow’s book. There were moments when he seemed to be on the verge of tears.

Despite the fact that Hamilton was “something of a human word machine,” to use Chernow’s formulation, devising such a compelling portrait was not an easy task. Like most of Chernow’s subjects, Hamilton had never been particularly forthcoming about his inner life, and only rarely talked about his youth in the Caribbean. Something about “famously secretive and reserved people” seems to attract Chernow. “I’m always envious of biographer friends whose subjects are writers and intellectuals, who keep intimate diaries and who pour out their thoughts and feelings in letters,” he complains, half in jest.

Such is obviously not the case for men like Rockefeller or Washington, or for Chernow’s current quarry, Ulysses S. Grant, despite the fact that Grant is the author of one of the most praised autobiographies of any American president. Chernow points out that Grant’s book passes over in near silence the destitution that threatened him before the war. “What my job entails, as a biographer, is to penetrate the silences,” he says, referring to those issues his subjects preferred not to confront during their own lives, and also to the disorganized matter of their early lives, when they were still becoming the historical figures they did not yet know they would be.

Such an emphasis on the formation of character can provide readers with insight into their own souls—and Chernow’s emphasis on great themes, not to say great men, can give them insight into their nation’s politics. “We as a country, whenever we face . . . very fundamental choices, those choices have to be informed by an understanding of history and the humanities,” he notes. There is room for academic historians to focus on social “bottom-up” history writing, but the very popularity of Chernow’s work demonstrates public hunger for books that provide civic insight and—though he wouldn’t himself necessarily put it this way—a kind of moral instruction that recalls Plutarch.

All this, so long as the writer remembers that it is virtually criminal to transform American history into a slog. To make his point, Chernow cites a remark of Gore Vidal’s he once overheard: “‘You know, we’ve had a short history but it’s been so colorful and dramatic, you have to work pretty hard to make American history boring.’

“And I agree with that!”