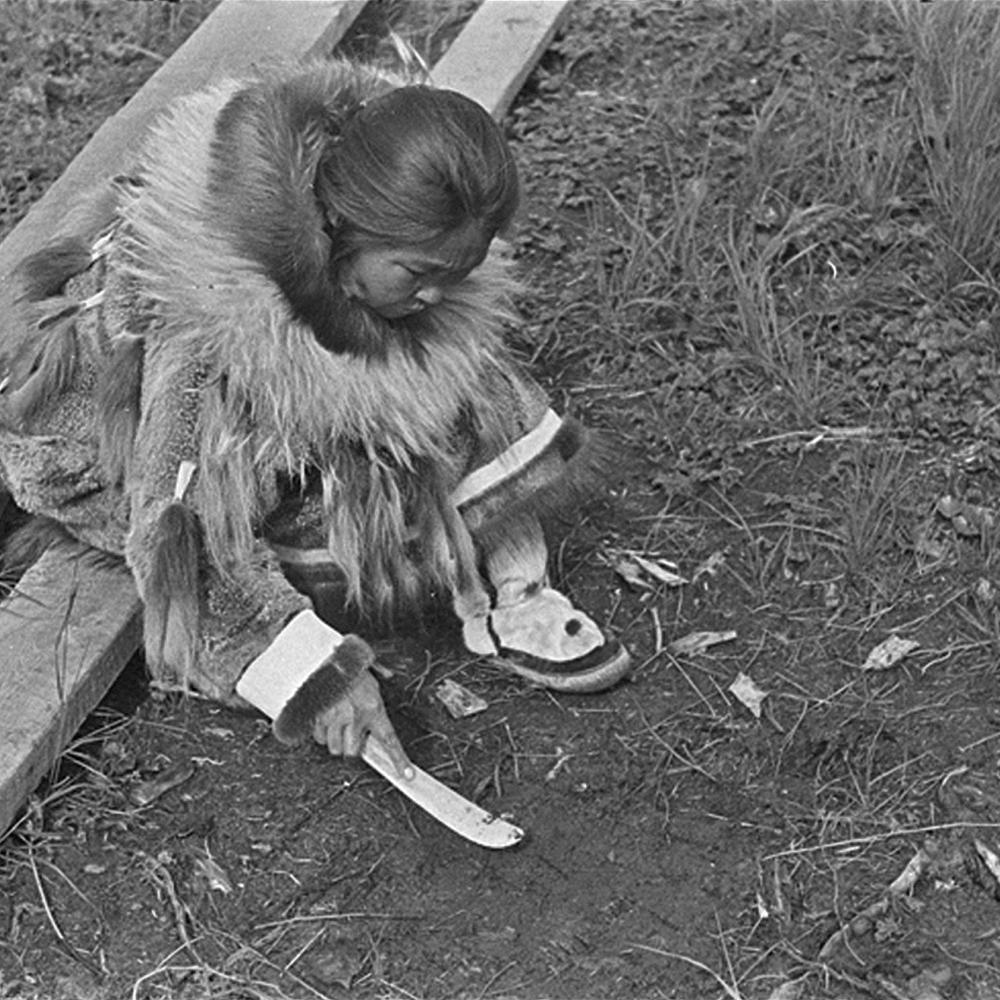

In the native Yup’ik communities of southwestern Alaska, it was once common to see groups of young girls crowded around a circle in the mud, engaged in a curious sort of game: One would be telling the others a story while simultaneously drawing intricate symbols with a knife on a flattened canvas of mud.

The practice is known as storyknifing, a Yup’ik tradition of mysterious origin that is estimated to be around three hundred years old. Russian explorer Lavrenty Zagoskin was the first to provide a written account of storyknifing in 1847 in a book about his travels through Alaska, which mentions native women drawing on the snow with ivory blades.The symbols, which can vary widely from village to village, illustrate the action in the story. A house’s interior, for example, would usually be drawn as a top-down diagram, while a person could be represented by anything from a stick figure to an abstract shape, with variations depending on the character’s age, gender, whether they were standing, sitting, talking, and other factors. When a story changes scenes, the storyteller simply wipes away the image and starts drawing a new one.

For Agnes Lewis David, a Yup’ik elder living in Kongiganak, Alaska, storyknifing is a fondly remembered part of her childhood in the 1950s and ’60s. “We used to do it a lot,” she says. “A couple of girls would bring a storyknife and one, only one, would tell stories, and all of us would listen to her.” Although boys generally understood the symbols, storyknifing is traditionally an activity for girls from the age of six through their early teens, and sometimes for mothers and grandmothers as well.

The storyknives were carved from wood, bone, or ivory, sometimes engraved with detailed ornamental designs. David’s own grandfather frequently made her storyknives when she was little. “He would already finish the storyknife every day. I don’t know how many times I went to him to get a wooden storyknife,” she recalls. Any knife could do in a pinch, though, even a humble butter knife.

With regards to storyknifing today, David observes, “They don’t use it no more in our area, where it was really strong when we were small.” She links this trend with the rising popularity of other forms of entertainment such as television. As a way of preserving this tradition, David is working to publish a book, with funding from the Alaska Humanities Forum, compiling some of the storyknife tales that her grandmother told her as a child, along with illustrations of the symbols that go along with each story.

“She would storyknife when she’s outside or when we had bedtime stories, too. And even tundra—when we go out in the tundra she would tell me stories,” David says. Much like other folktales, these stories often contained a moral.

In “The Boy Who Didn’t Listen to His Parents,” a boy is told not to go outside at night, even if he has to go to the bathroom. Naturally, he wakes up one night needing to use the bathroom, and, seeing a faint glimmer of sunlight outside his window, decides to leave the house. He is met by an old woman who kidnaps him and locks him away in her house, far away. A young woman passing by the house frees him from captivity, killing the old woman in the process, and then takes care of the boy until he is strong enough to return home.

Each story in the collection has an English translation, but is also written in Yup’ik, using two different orthographies: One was developed by Moravian missionaries in southwestern Alaska during the late nineteenth century, while the other was designed in the 1960s by linguists at the University of Alaska to be easily typed and to more accurately represent the sounds of the Yup’ik language. “This new generation is reading more of the new system writing,” David explains. “They’re not used to reading the old system. But we still use old system readings from the New Testament of the Bible.” By providing the stories both ways, this collection aims to help preserve not only the practice of storyknifing, but also an entire writing system that has begun to fade from use.

There is still hope that storyknifing will continue to be a part of Yup’ik culture. When David worked in Bureau of Indian Affairs schools in the 1970s, she would take her students outside on nice days and tell them storyknife tales. She says that they loved it.