A humanist is not just any human. A humanist is one who searches for what it means to be human. In this issue we look at a few who have gone to extreme lengths in their searches. Celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of NEH, Humanities magazine presents the stories behind their major achievements.

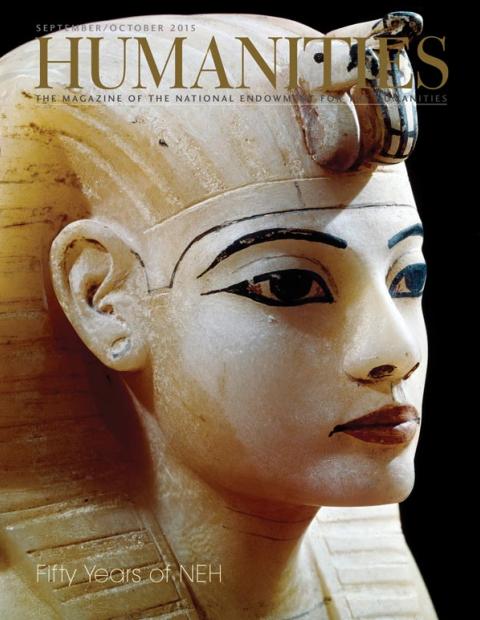

Howard Carter had put shovel to sand numerous times in the Egyptian desert. His patron, the fifth Earl of Carnarvon, was about to cut him off, then consented to one more year of searching for the tomb of Tutankhamun. Carter soon hit pay dirt. And, as Meredith Hindley reports, half a century later, President Nixon and Henry Kissinger used a bilateral agreement with Egypt to bring the glories of ancient Egypt to America in a triumphant and exhausting national tour, supported by NEH.

When Ken Burns decided he wanted to make his next film about the Civil War, not just a single battle or individual but the whole bloody narrative, his own father was incredulous. It was the mid ‘80s and the New York Times took note of Burns’s “unconventional” use of still photos and voice overs, but, as Peter Tonguette shows, this NEH-supported undertaking would require even greater creative breakthroughs. Twenty-five years ago,The Civil War debuted to almost universal acclaim.

The story of NEH was only half begun when Senator Claiborne Pell began pressuring NEH’s first chairman, Barnaby Keeney, a former president of Brown University, to figure out how to extend humanities funding and programming to the local level. Keeney was not exactly keen on the idea, but in a few years, fifty state humanities councils were up and running. Esther Ferington describes the moment when they came to life.

Philip Kelley was a student when he began working at the Armstrong Browning Library at Baylor University. Answering queries from scholars in search of letters between Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, he noticed it would be most helpful if he learned the whereabouts of all such letters. Soon he uncovered many heretofore unknown letters between these famous Victorian poets, so he began publishing them, in scholarly editions, without any kind of university or research institute backing him. After two days with this self-taught, critically lauded editor, Nicholas Basbanes tells us about Kelley’s strange and beautiful accomplishment.

The Library of America began as a gleam in the eye of the great literary critic Edmund Wilson, who complained to his friend Jason Epstein about the lack of a uniform series of books devoted to classic American writing. It was easy enough to find The Scarlet Letter in paperback, but what about all the other great writing that America’s growing ranks of college graduates might want to enjoy and preserve? It took almost a quarter century, and a good bit of bickering, for Wilson’s dream to be fulfilled.

A half century after President Johnson signed the legislative act founding the National Endowment for the Humanities, NEH is looking back at many projects that helped articulate the great ambitions of the agency’s founders. These are but a few.