Was there anybody Studs Terkel didn't know?

The famed broadcaster and author had enough friends and acquaintances to last several lifetimes, so it’s no surprise when he pops up in Michael Moore’s 1998 film The Big One.

Midway through the documentary, in which Moore travels the country hawking his book Downsize This!, the provocateur filmmaker drops in on Terkel at 98.7 WFMT, the Chicago radio station that was home to Terkel’s interview program for over four decades.

Excited to have him, Terkel cues up John L. Handcox’s classic folk song Roll the Union On, which Pete Seeger, who ought to know, once called, “a great picket line song. One of the greatest ever.” The song is rousing, but it is Terkel—and his endearing, revealing reaction to it—who captivates.

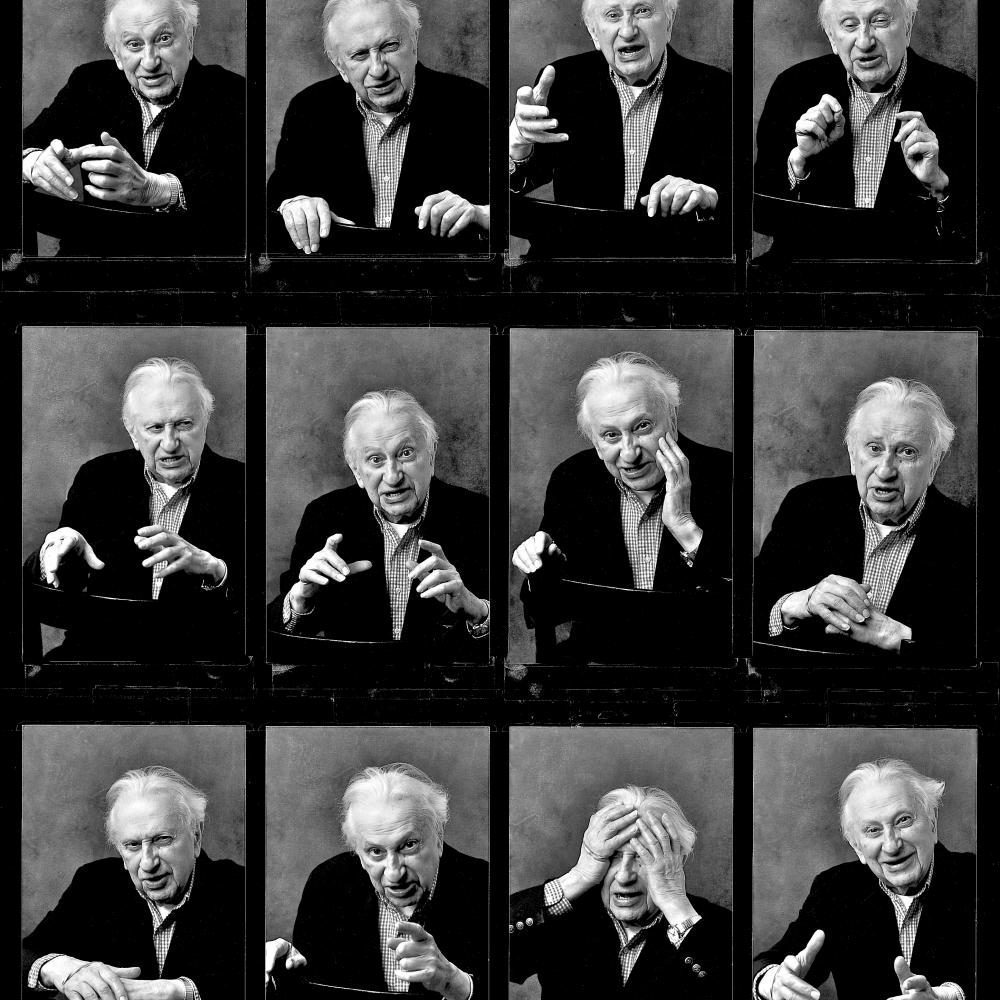

“One more verse!” he barks several times to an off-camera radio crew. Outfitted in his signature red sweater—his white-maned head dwarfed by oversize earphones—he moves his arms to orchestrate the music, never mind that it’s a recording.

His microphone before him, Terkel stammers and murmurs the lyrics: “We’re gonna roll . . . We’re gonna roll the union. . . .”

At this moment, the rascally radio hand is north of eighty, but he’s no old man lost in a reverie. In fact, he is downright sprightly.

With impeccable timing, he brings the volume down by lowering his hands. Then, effortlessly, he transitions to his guest—a native, of course, of Flint, Michigan: “Hearing that song of the thirties, of the Flint sit-down strike of labor, the CIO” Terkel says, stressing thirties and C-I-O, before drawing out the connection, “seated next to Michael Moore.”

Some may argue that Moore is unworthy of so grand an introduction, or that Terkel’s sentiments reveal an unbecoming naïveté. But it’s hard to not be won over by Terkel’s joyful display of conviction.

Here, one thinks, is a contented man, secure in his take on history and pleased as punch to have cast his lot with the downtrodden. He could be among those who, for Carl Sandburg, exemplify “happiness” in his great poem of that title: not the “famous executives who boss the work of thousands of men,” but rather the “crowd of Hungarians under the trees with their women and children and a keg of beer and an accordion.”

Born in New York City in 1912 as Louis Terkel, he affixed “Studs” to his name—he writes in his 2007 memoir Touch and Go—after he graduated from law school at the University of Chicago and was trying to make it as an actor. Cast in Clifford Odets’s Waiting for Lefty, he writes, “two other guys in the cast were named Louis. . . . At the time, I was entranced by the writings of James T. Farrell and his Studs Lonigan trilogy. Everyone started calling me Studs.”

And the name does justice to Terkel’s one-of-a-kind life, too: Just as his law degree did not stop him from pursuing acting, the blacklist—which resulted in an early television show, Studs’s Place, being canceled—did not dampen his determination to broadcast, loudly, his particular brand of politics. In 1952, WFMT’s The Studs Terkel Program began airing, and it did not cease until some forty-five years later, in 1997. (“I’m not suggesting you be on the blacklist,” he said in 1999, in an interview with the Archive of American Television, but “were it not [for] that I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing today.”) His personal life—like his professional life, and like his political beliefs—was a study in continuity: His wife, Ida, died in 1999, after more than sixty years of marriage.

There aren’t many media figures who were alive during the Woodrow Wilson administration and yet remain influential in the twenty-first century, but Terkel is one. And his admirers are an au courant bunch, ranging from crime novelist Walter Mosley to radio host Garrison Keillor. Terkel’s part in the development of the oral history form—that is, books in which interview subjects tell their stories without assists from a narrator—is widely acknowledged.

About a week after Terkel’s death on October 31, 2008, Ira Glass tipped his hat on This American Life. “Oral histories were around before Studs started doing them,” Glass said at the time, “but he pretty much redefined them and did them so amazingly well that anybody who comes after can’t help but be influenced.”

Alex Kotlowitz, acclaimed author of There Are No Children Here, was a friend, and he, too, sees Terkel’s impact as stretching far and wide. “You look at [Haruki] Murakami, the Japanese novelist, wrote a book called Underground, which was a collection of kind of oral histories about the gas attacks in Tokyo, and he gives a nod to Studs at the very beginning of that book,” Kotlowitz said, adding that Terkel “created this genre.”

Extraordinarily prolific, he certainly contributed to it: Concurrent with his radio career, which kept him busy five days a week, Terkel assembled a formidable bunch of oral history-style books, among them the best-selling Working (1974) and the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Good War (1984). Others concerned the Great Depression (Hard Times, published in 1970), Chicago (Division Street: America in 1967), and the specter of senescence (Coming of Age in 1995).

The almost six-hundred-page Working—which might be more accurately called Doing, since it takes as its subject nothing less than the seen and unseen effects of exertion, whether for remuneration or not—is staggering in its scope: an introduction, three so-called “prefaces,” and nine “books” consisting of some twenty-six main chapters (including “Working the Land,” which refers to farmers and the like, and “Footwork,” a category broad enough to include—yes—a shoe-factory employee, but also a mailman and a gas meter reader). In all, the book presents over 130 interviews related to its enormous theme, but such length—hardly an anomaly in the Terkel canon—has its drawbacks.

Earlier this year, Peggy Shinner, a professor at Northwestern University, contributed to the Chicago Reader’s contest to determine the greatest book related to Chicago. Working ended up as one of the finalists, but on Shinner’s first go at the book, she wrote, “torpor set in; the book was almost unreadable. In fact, it’s not meant to be read. It’s like an encyclopedia, meant to be consulted, sampled.”

But much of its power depends on the reader noticing the different kinds of work (from proofreader to gravedigger) as well as the differing views on work. The words of the overwrought former airline reservationist (“I was taking eight tranquilizers a day”) are meant to seem at variance with those of the sensible stockbroker several hundred pages later (“Our system depends on a free exchange of publicly owned assets, and we’re part of the picture”). Read in isolation, however, the divergences and similarities are lost.

The repetitiveness of Working—as with many other Terkel tomes—is wearying. The reflections of not one but a trio of youngsters with newspaper delivery routes are included, and, for reasons unclear, Terkel deemed it necessary to preserve the accounts of two barbers, a hair stylist, and a cosmetics clerk.

There is an idea here. As the steelworker Mike LeFevre says, “I would like to see a building, say, the Empire State, I would like to see on one side of it a foot-wide strip from top to bottom with the name of every bricklayer, the name of every electrician, with all the names.”

Terkel too seemed to want all the names, as many voices as possible. “He Interviewed the Nation,” was the title of Garry Wills’s reminiscence in the New York Review of Books. At the risk of seeming uncharitable, however, it should be said that not all of the nation is equally fascinating to interview.

Asking an average person to ruminate on an aspect of his or her life, however, was an uncommon request in the years during which Terkel’s best-known books were assembled. As Kotlowitz recalled: “Studs always used to tell the story of an interview he had done in the 1960s with a woman in the projects, and after the interview the woman asked him to replay the interview for her and he replays the interview. She just sat there, just completely attentive to what she was saying, and when it was all done, she turned up to look at Studs and says, ‘You know, I didn’t know I thought that way.’”

Working has its share of great moments: the way hotel piano bar player Hots Michaels revels in the hustle-bustle of his job (“If I were suddenly to inherit four million dollars, I guarantee you I’d be playin’ piano, either here or at some other place. I can’t explain why. I would miss the flow of people in and out”), or the pride of supermarket checker Babe Secoli in belonging to a readily identifiable occupation (“There’s some, they say, ‘A checker—ugh!’ To me, it’s like somebody being a teacher or a lawyer”). But would any of the memorable parts of Terkel’s oral histories—the lasting thoughts, the quotable lines—have been diminished if he had cut the less memorable parts? Or if he had forsaken the oral history format altogether and become the primary teller of his subjects’ tales?

Alex Kotlowitz praised Terkel’s efforts in molding his books: “I don’t think anybody sort of realized . . . the kind of thought and care that went into those interviews, to finding the right people, and then the kind of editing that went into making them a cohesive whole.” And Terkel’s editor, André Schiffrin, was quoted in a 1989 Orlando Sentinel article, saying that Working began with “about a million words,” but the book ended up being “only about a tenth of that.”

Yet it is also obvious that most of Terkel’s books would have been sharper and fleeter had he been choosier—he was not, after all, providing a public service (step right up and tell your troubles to Studs), but trying to put together a book.

And there is something of a blank spot where the author should be. Even questions seem to have been edited out. Those that remain are usually of the most basic, boring variety: “What did you want to be?”; How do you feel about Ralph Nader?”; “Were there any complaints?”

Restraint was not actually what Terkel was known for. “I think the kind of glib thing to say about Studs is that he taught us all how to listen,” Kotlowitz said. “But I think anybody who knew Studs knows that the guy just couldn’t shut up. I mean, he loved to talk.”

All the same, several critics have argued that Terkel is too much of a presence in these oral histories—that his unseen hand is present even when his voice has been excised. “It is, in fact, impossible,” wrote the critic Edward Rothstein in the New York Times, “to separate Mr. Terkel’s political vision from the contours of his oral history.” Rothstein added, “Mr. Terkel seems less to be discovering the point latent in his conversations than he is in shaping the conversations to make a latent point.”

And there was a tendency to favor public figures cut from a similar political cloth (film critic Pauline Kael in “The Good War”; novelist Kurt Vonnegut in 2001’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken?; former Democratic congressman Dennis J. Kucinich in 2003’s Hope Dies Last), a proclivity bemoaned by Rebecca Pepper Sinkler in a review of Coming of Age in the New York Times: “The people interviewed for Coming of Age, though diverse in their life histories, are an inordinately like-minded crowd, and the language spoken here is pure Terkel: the voice of the embattled old liberal shaking his stick at the 20th century.”

Ironically, the more we hear from Terkel directly on his show—without any pretense of honoring the oral historian’s quietude—the less we mind his “political vision” or “latent points,” as Rothstein calls them. Coming out of his mouth, they seem at worst quaint and at best charming—because Terkel was both.

In 1965, introducing “one of the funniest men I’ve ever seen,” Terkel nearly refers to Woody Allen by the name of a rather different entertainer: “I was about to say Woody Guthrie.” No matter—the conflation is an appealing Freudian slip. The interview itself is a model of good dialog.

Terkel compares Woody—Allen, not Guthrie—to a Jules Feiffer cartoon: “You’re real, yet at the same time you’re a cartoon but yet you’re very endearing and very attractive—how can you explain that?” It’s the kind of insightful, engaging question—and one Allen keenly picks up on (“Nearly everything I talk about has happened to me, but not nearly as exaggerated as I’ve made it,” Allen admits)—too often missing from Terkel’s books.

This interview is among those accessible on the still-growing WFMT Studs Terkel Radio Archive. Listening to Terkel talk with Tennessee Williams or Louis Armstrong, we are reminded that a healthy portion of Terkel’s work has nothing to do with woebegone proletarians. He hosted a jazz program early in his career, and his first book—not an oral history—was the superb Giants of Jazz (1957). This collection avoids the pitfalls and longueurs of many subsequent books with its pithy portraits, which show that Terkel was a gifted writer when he sat down to the task.

Consider this sensitive and crisply written snapshot of Billie Holiday’s youth in 1920s Baltimore: “Those who couldn’t afford private maids hired children of poor families to scrub and keep clean the steps. Among those thus employed was Billie Holiday. She was six when she made her first nickel as a ‘scrub woman.’” Terkel adds, “Perhaps it was this kind of lost, ‘grown-up’ childhood that inspired one of Billie Holiday’s most touching songs, ‘God Bless the Child.’”

Garry Wills judged The Spectator (1999)—a delightful grab bag of interviews with those in the performing arts, from Agnes De Mille to Marcel Marceau—to be Terkel’s best book. It certainly has plenty of wonderful and eclectic material. Lillian Gish reveals that she felt her schooling in movies inferior to the college educations of her cousins before realizing the advantage she had. “Think of the education of Intolerance. That was the greatest film ever made,” she says. Arnold Schwarzenegger praises the United States for the opportunities it offers for advancement. The book’s most pleasing quality is, inevitably, Terkel himself. Happily, more than a few interviews preserve Terkel’s utterances, which can be boyishly enthusiastic. “I’ll never forget the first movie I ever saw you in: Sinner’s Holiday,” he tells Jimmy Cagney. After Ian McKellen says he was inspired by the tennis court demeanor of John McEnroe in preparing for a performance of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, Terkel says, “I get a kick out of the way your mind works.”

In an interview with Arthur Miller, excerpted in The Spectator, one comment by Terkel says more about Terkel than any comment by Miller says about Miller. During the otherwise bleak years of the 1930s, Terkel says, there was nonetheless “a camaraderie: the passing of a cigarette butt to another, a streetcar transfer changing hands, a morning newspaper handed over to the next guy.” So much for “hard times”—those were glory days for Terkel.

We are back to where we started: Terkel, the interviewer as interesting as many of his sources, and sometimes more, even with his gushing, romantic leftism.

Actress and playwright Anna Deavere Smith, who has performed as Terkel on stage, was a guest on his show. “He invited me to lunch after the interview—in fact, he assumed we would have lunch,” Smith said in an e-mail. “This is a bygone tradition.” She could not join him for lunch that day, but on a subsequent occasion, when the two found themselves in New York, “we went to a ‘joint called the Crocodile,’” she said. “Those are Studs’s words, not mine.”

Smith continued, “We each ordered a whole fish and filleted them ourselves. Studs pulled his bone out of his red snapper with great aplomb. When the check came, he went for it, but I mumbled to the waitress not to give it to him. As you know, Studs had trouble hearing and he did not hear me do it. He was stunned that I paid the check and never got over it. Studs was old-fashioned—he’d invited me—not the other way around.”

Terkel will probably endure for who he was rather than what he did. There is no shame in such a legacy. If we remember Orson Welles for his oratorical authority or Norman Mailer for his self-fashioned image of bravado—instead of many of their actual works—why not Terkel for his firecracker of a personality?

“He had high expectations that we could reach the best in ourselves,” Smith said. “When he was quite old, he was robbed—mugged in Chicago. Just as the thieves were about to go off with all his money, he asked, ‘Hey, can you give me enough back to take the bus?’”

Who could tire of such a man?