In 1980, Greg Hoots rolled into Alma, Kansas, a cocky young deliveryman desperate to save his job.

Told by his United Parcel Service boss he’d no longer be needed after the Christmas rush, Hoots jumped at a chance to postpone the layoff by covering a rural route in Wabaunsee County for a week.

The supervisor asked if he knew Wabaunsee. “I said, ‘I know it like the back of my hand,’” Hoots recalls with a laugh. “I’d never been here before in my life!”

When he retired from UPS after serving three decades as the county’s go-to guy for packages and parcels, he could truly say he knows Wabaunsee County—not only its small towns and back roads, but also the history and culture of its people.

“There’s not a road in this county, no matter how remote, that I haven’t been down a hundred times,” says Hoots, who lives one hundred miles east in Kansas City. “You see all these remnants from the past, old buildings and ruins. They’re everywhere, right there for you to see.”

But the real history lessons came from Wabaunsee residents themselves. “Once I got to know people, they would tell you their stories. That’s where I learned the history.”

Hoots parlayed those stories into several photo books that chronicle the county and the surrounding Flint Hills region. His research drew heavily on photo archives at the Wabaunsee County Historical Society & Museum, and after retiring in 2012, he became the first nonresident to join the organization’s board of directors. His first project—funded by a Kansas Humanities Council grant—preserved more than nine hundred historical photographs of Alma and adjacent communities.

Displayed in glass panels that exposed the photos to sunshine, fluorescent lighting and moisture, the photos of apple harvests, a gas station grand opening, family picnics, and community celebrations were endangered and inaccessible to museumgoers, who often requested copies after spotting familiar faces and places among the scenes of everyday life. Hoots wrote the grant application and raised matching private donations, then volunteered his time to remove photos from the display and make high-resolution scans of each before storing them in acid-free sleeves.

Now the digital images can be displayed on the museum’s website and easily shared with patrons who crave a piece of their past to share with family and friends. It’s exactly the sort of accessible, grassroots history that community museums should do, Hoots believes.

“The biggest role of a museum like ours is not just the preservation but the presentationof local history,” he says. “We provide a great resource for people in the community to explore their heritage. The state archive has a half million photos; we have only a few thousand, but all are from here. The state has an obligation to tell a much bigger story, but we can tell our story better than anyone else.”

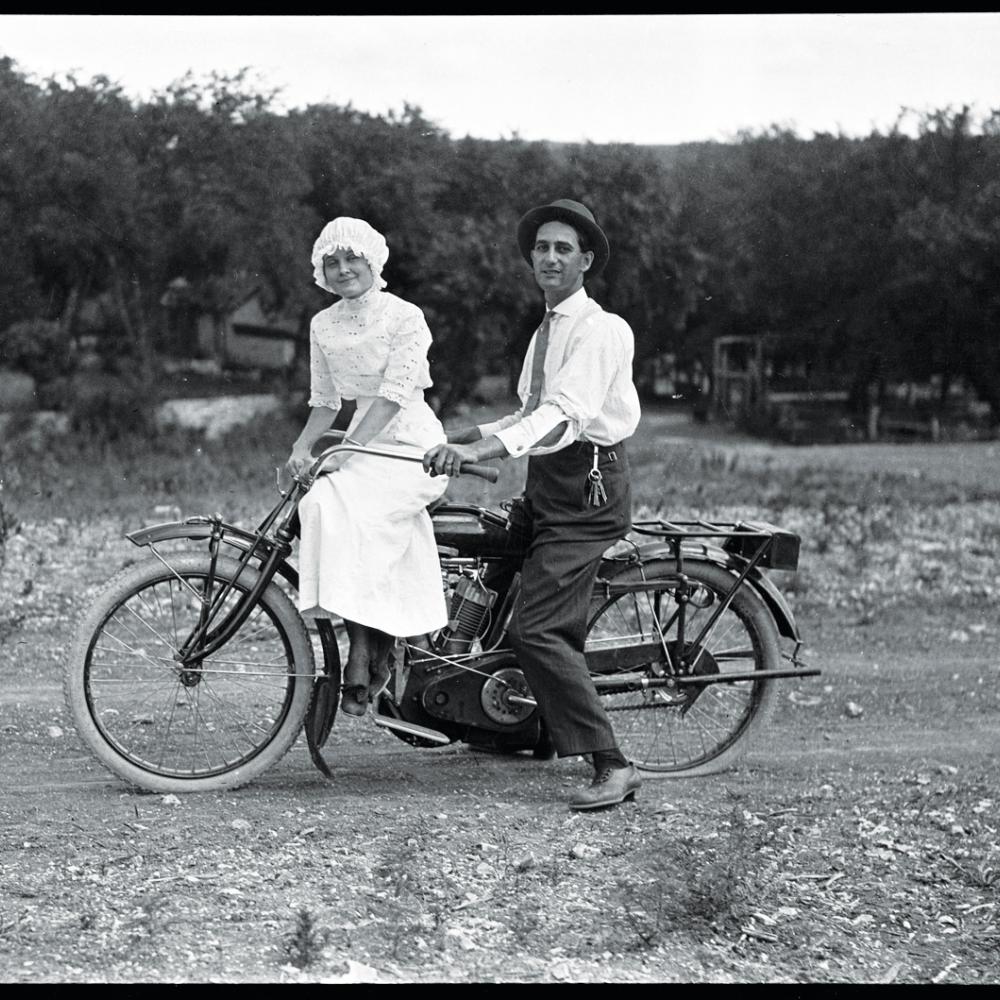

His next project is preserving 2,500 photographs that local merchant Otto Kratzer took between 1905 and 1965. Hoots recovered glass negatives and home movies from Kratzer’s daughter, and he’s organizing exhibitions and a documentary film about the late shopkeeper and postmaster, whom he calls “a big, flamboyant character with an eye for history.”

The description could apply to Hoots as well. His lifelong love of photography (kindled at seven when his father gave him a box camera) and enthusiasm for Wabaunsee County drove him to find a buyer to restore Kratzer’s long-abandoned general store and convert it to a community center. Among those impressed by his energy is Julie Mulvihill, director of the Kansas Humanities Council.

“Greg not only saw that Wabaunsee County has something special, he did something about it,” Mulvihill says. “He realized that without attention and care, the photos that tell the county’s story could be lost, and he took it upon himself to save them. That kind of enthusiasm is a treasure, and it’s essential with these kinds of preservation projects—because the to-do list seems neverending.”

“Studying one’s family history, the history of their town, their county, their state—that’s enriching for people,” says Hoots. “To get to know where they came from, who their ancestors were, what had to happen for us to be here today, for me that’s what it’s all about.”