Children of the Plumed Serpent

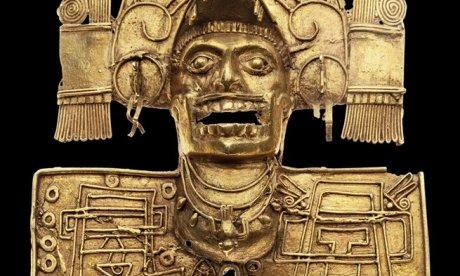

Unknown, Pectoral with Calendrical Notations (AD 700–1300), gold, 4 ½ x 1/16 in (11.5 x 2 cm), 3.93 ounces (112 grams), Museuo de las Culturas de Oaxaca. Photo © Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia (CONACULTA-INAH-MEX), from the exhibition Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California.

Courtesy, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. www.lacma.org

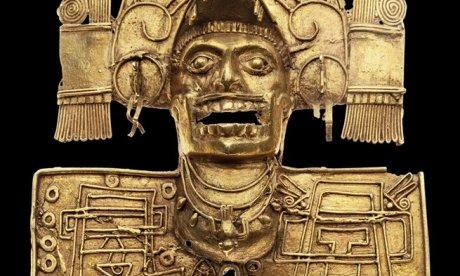

Unknown, Pectoral with Calendrical Notations (AD 700–1300), gold, 4 ½ x 1/16 in (11.5 x 2 cm), 3.93 ounces (112 grams), Museuo de las Culturas de Oaxaca. Photo © Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia (CONACULTA-INAH-MEX), from the exhibition Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California.

Courtesy, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. www.lacma.org

Artistic motifs can offer striking evidence of cultural survival. Though they were at times overrun by other indigenous peoples such as the Aztecs or by the Spanish conquistadors, the early native peoples of southern Mexico proved to be remarkably resilient. Their cultures flourished during roughly the 10ththrough the 15th centuries. Such nations claimed descent from the earlier and powerful Toltecs, once the center of a bustling empire. One key heroic and legendary figure inherited from the Toltecs was the man-god Quetzalcoatl. Seen as the human incarnation of the spiritual forces of wind and rain, Quetzalcoatl was typically portrayed in art as a plumed serpent, a longstanding motif in Mesoamerican sculpture and painting. The confederacies of southern Mexico created elaborate trade networks and shared unique styles of architecture, ceramic traditions, and written communication. Their sense of common ancestry fueled the growth of the cult of Quetzalcoatl and produced common artistic motifs throughout Mexico, even reaching as far as what is today the southwestern United States.

When the Aztecs rose to power in the 15th century, they disrupted the political autonomy of these powerful confederacies, but did not eliminate them, choosing instead to leave them in place as long as they paid the required tribute. A hundred years later the Spaniards would follow a similar path, opting simply to replace the Aztec administrative structure with their own. Thus, traditional forms of artistic production and exchange and tribute collection survived. Local leaders, known as caciques, who oversaw these activities, managed to establish a new mixed identity, appearing Spanish in terms of visible dress and speech but all the while sustaining traditional beliefs and forms of artistic expression such as the mythic figure of Quetzalcoatl.

This story of the remarkable persistence of cultures is told in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s exhibition Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico. Through a rare combination of ceramics, codices, artifacts of turquoise, gold and shell, paintings, and other items, the exhibition highlights the important role art can play in defining and maintaining social, political and economic ideologies. It also suggests how ongoing traditions in some Mexican communities today can give us a fresh look at the past. The exhibition was at LACMA through July 1, 2012, and featured an assortment of lectures and other public programs. It then traveled to the Dallas Museum of Art (July 29–November 5, 2012). For further information, follow this link: http://www.lacma.org/art/exhibition/children-plumed-serpent-legacy-quetzalcoatl-ancient-mexico