Winter Takes Over the News: The 1922 “Knickerbocker Storm” in Chronicling America

The storm of 1922 named after the Knickerbocker Theatre is still the largest snow storm on record.

Courtesy the National Archives

The storm of 1922 named after the Knickerbocker Theatre is still the largest snow storm on record.

Courtesy the National Archives

As the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast coastal regions continue to dig out from the massive snowstorm of this past weekend, meteorologists have turned to the record books to see where this event ranks among history’s most extreme winter outbursts. For Washington, DC, the verdict is still uncertain, but we do know that the blizzard of 2016 – officially Winter Storm Jonas but more popularly dubbed “Snowzilla” – fell short of eclipsing the snowfall amount from what is commonly referred to as the Knickerbocker Storm, occurring 94 years ago this week.

These two storms share some striking similarities and some important distinctions, a major one being the reason for the name of the 1922 event. On January 28 of that year, snow accumulation caused the collapse of the roof of the Knickerbocker Theater on 18th St. and Columbia Rd. in Washington’s Adams Morgan district, resulting in extensive loss of life, injuries, subsequent investigations, and lingering tragedies. Coverage of the Knickerbocker Storm and its immediate aftermath was plentiful in local newspapers, as well as others across the country, and can be explored through the Chronicling America online newspaper collection.

What is Chronicling America?

Chronicling America is a freely accessible web site providing information about and access to historic United States newspapers published between 1836 and 1922. To date, 10 million pages representing 38 states and territories and the District of Columbia are available on the site, with more being added all the time. Chronicling America is produced through the National Digital Newspaper Program, a partnership between the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and state projects. NEH awards enable states to select and digitize newspapers that represent their historical, cultural, and geographic diversity, and to contribute essays containing background information about each newspaper and its historical context. The Library of Congress unifies all content provided by states and permanently maintains the digital information. Chronicling America is freely available on the internet, and users may search the millions of digitized pages and consult a national newspaper directory to identify newspaper titles available in all types of formats.

“Snow or Rain Probably”

Like Snowzilla, the Knickerbocker Storm of 1922 took aim at the Mid-Atlantic from the South moving slowly northeast along the coast where it clashed with very cold temperatures. Coincidently, the snow fell in Washington from Friday afternoon through much of Saturday. However, unlike Snowzilla, the storm in 1922 was not predicted days in advance, and residents were caught off guard. In fact, the Final Home Edition of the Washington Times on Thursday, January 26, offered a forecast of "Fair tonight and probably Friday; slowly rising temperatures." It wasn’t until the following day, when the storm system was settling in on the region, that local forecasters began to see the picture unfolding, albeit imperfectly, as evident in the January 27 announcement in the Washington Herald: “Snow or rain probably tonight and tomorrow."

Snow it did. “Capital is Snow-bound,” read the large headline from the January 28th Washington Times, overtaking (but not completely eliminating) the salacious stories of extramarital affairs involving prominent local citizens that had been dominating that paper’s front-page coverage for some time. Beginning around noon on the 27th, as much as 24 inches had fallen by the next morning, according to local papers. That conjured up memories of another huge blizzard in 1899 and a search for information on that and other previous storms. However, Washington’s Evening Star reported that the Weather Bureau’s climatological records for those years had gone missing: “When request was made of the observatory at the bureau for figures, officials were forced to reply that they couldn’t find the book. ‘Somebody has taken the book away,’ said an official. ‘Guess it must be some place around the building.’” Eventually, records were located, and it was determined that the 1922 storm brought the largest amount of snow ever for a 24-hour period.

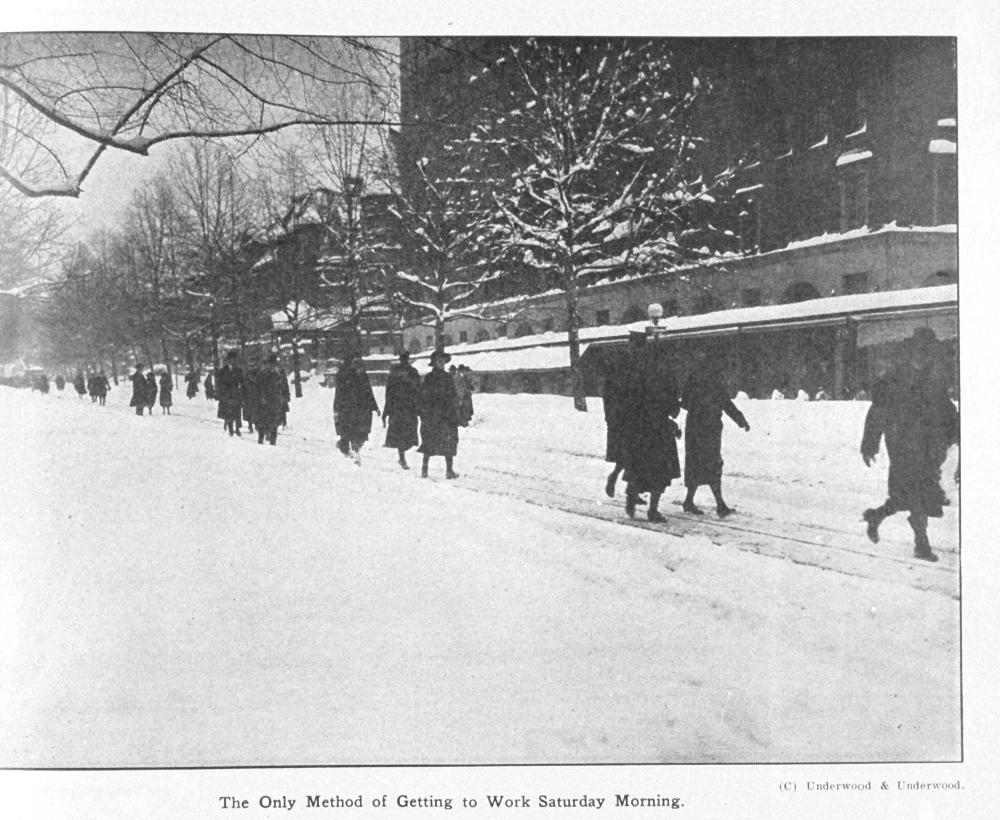

As would be expected, transportation in the nation’s capital was severely affected for a number of days, particularly local rail services, but the papers reported optimistically on ongoing efforts to plow roadways and clear street car lines. They noted, too, the temperament of the city residents, which was cast as generally upbeat. The Evening Star commented that “Everybody seemed to be in jolly mood, including street car employees, and the people struggled to work in cars and afoot.” Federal employees who had to report to work that Saturday were released at noon, as forecasts called for continuing snow.

By Monday, though, the city began to attempt resuming normal activity. Although Washington schools were closed that day, government workers returned their offices, as possible. This was clearly a struggle for many, however, as reported in the Washington Herald on January 30. The Washington Railway and Electric Company promised that “practically every line would furnish normal service” that morning, but this was clearly not the case the evening before, when evening rush hour resulted in major snarl ups on all available rail lines. Still, the paper speculated that “with the promise of fair weather by the Weather Bureau today and tomorrow…, the blizzard soon will be but a memory.” Schools reopened on Tuesday.

”A Stunned Silence Fell Over the Scene”

But this storm brought about a catastrophe that would make it much more than “but a memory.” Shortly after 9:00pm on Saturday, January 28, 1922, the roof of one of the city’s most popular movie houses gave way under the weight of over two feet of snow. Inside, moviegoers had settled into their seats following intermission of the silent film, “Get Rich Quick, Wallingford.” Audience estimates in early news reports varied anywhere from 150 to 1,000 attendees; the eventual death toll was determined to be 98, with 133 injured. The victims included a number of prominent residents, including a former U.S. senator and several local business and civic leaders.

The news made headlines the next day as far away as Ogden, Utah, and Bisbee, Arizona. As would be expected, local papers offered especially vivid accounts, such as this from the Washington Herald:

Men and women screamed and tried to jump from their seats, but the falling roof caught most of them. Then, as the sound of crashing timbers and girders died away, a stunned silence fell over the scene. Several persons passing on the street came running toward the theater when they heard the noise of the crash. Soon the smothered moans and shrieks of the injured could be heard coming from under the wreckage.

The Herald also described the ensuing chaos surrounding the building, with thousands of panicked onlookers and the summoning of infantry from Fort Myer in nearby Arlington, Virginia, to maintain control, with orders to shoot if necessary. Meanwhile, the Sunday Star of Washington immediately published lists of known fatalities and injured persons on its front page, including descriptions such as “unidentified man with sandy hair, V.L. on brass belt buckle”, to aid those looking for loved ones.

The news accounts reflect a city in shock and disbelief, even while working valiantly to bounce back from the crippling effects of the storm more generally. The January 30 edition of the Evening Starincluded a statement from the person who had previously coined the term “normalcy,” President Warren G. Harding:

I have experienced the same astounding shock and the same inexpressible sorrow which has come to all of Washington, and which will be sympathetically felt throughout the land. If I knew aught to say to soften the sorrow of hundreds who have suddenly bereaved, if I could say a word to cheer the maimed suffering, I would gladly do it. The terrible tragedy, staged in the midst of the great storm, has deeply depressed all of us and has left us wondering about the revolving fates.

Demands for accountability in the immediate wake of the disaster led to the establishment of a federal grand jury already by January 30, while Kansas Senator Arthur Capper introduced a resolution for a thorough investigation. Meanwhile, various theories emerged on what may have contributed to the roof’s collapse, one of the more interesting being the music performed during the silent film. As the Washington Herald reported, “Slight swayings, which may have been caused by certain notes struck by the orchestra, or the large pipe organ, possibly assisted in making the roof supports insecure, according to several noted scientists and experts upon sound action.”

Ultimately, a number of investigations at local and federal levels concluded that the building’s design, including the use of arch girders instead of stone pillars, was significantly to blame. Although no one was sued, both the architect and owner of the Knickerbocker Theater, sadly, committed suicide several years later.

The after-effects of Snowzilla are still upon us, and stories of tragic outcomes continue to emerge. But thus far it does not appear that this event will live on in history to the extent of, and in the same way as, the Knickerbocker Storm of 1922.

![The Washington times. (Washington [D.C.]) 1902-1939, January 28, 1922](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2018-08/washington_times_1-28-resize.jpg?itok=zYAq7Lt5)