W.E.B. Du Bois in Cyberspace

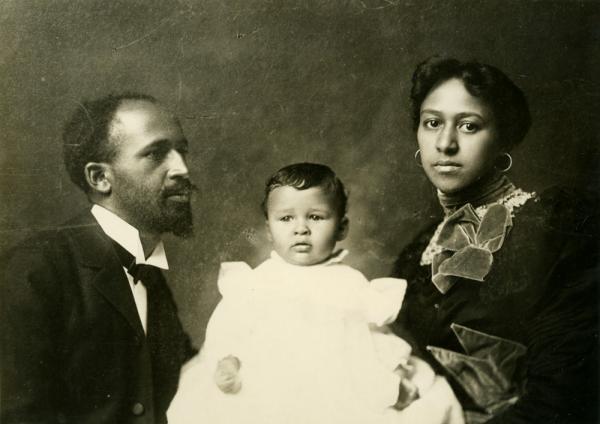

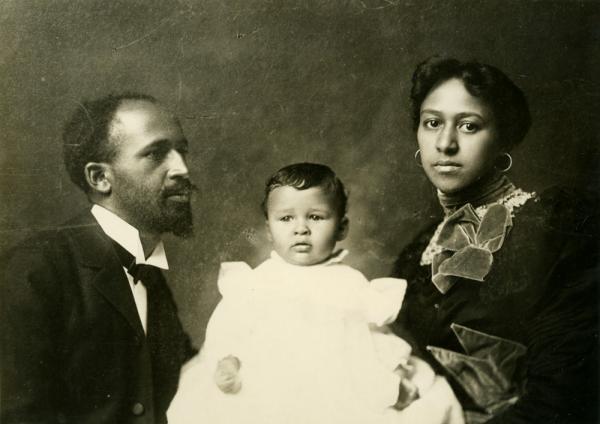

W. E. B. Du Bois, son Burghardt, wife Nina, 1898. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312).

Courtesy of the Special Collections and University Archives, University Libraries, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

W. E. B. Du Bois, son Burghardt, wife Nina, 1898. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312).

Courtesy of the Special Collections and University Archives, University Libraries, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

W.E.B. Du Bois stands as one of the twentieth century's deepest thinkers and greatest writers, whose extraordinary gifts as a scholar helped shape modern sociology, and whose social conscience shaped the global movement for civil rights. His complete papers are now freely accessible online, which presents an exceptional opportunity to conduct thorough research. Liberated from the physical bounds of paper and place, sociologists and historians, literary scholars, cultural critics, students, archivists, and artists from around the world are interacting with Du Bois's writing and in the process finding new contextual meaning a century later.

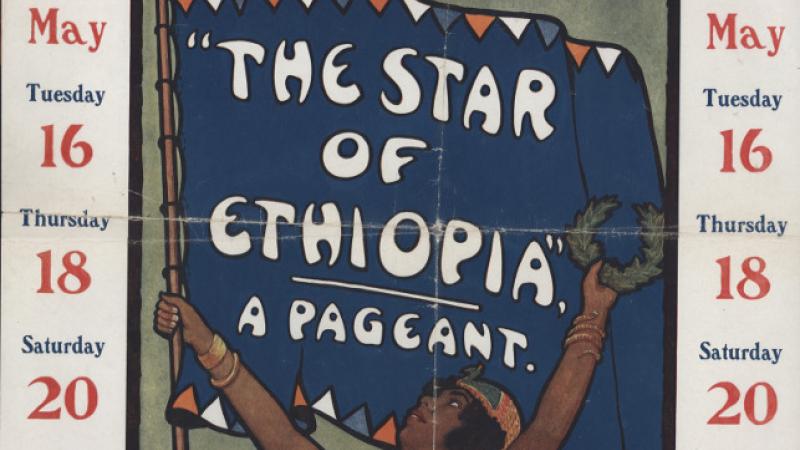

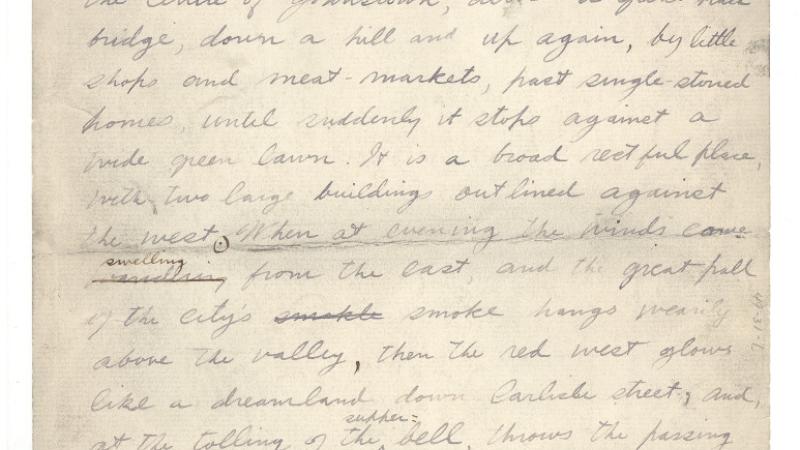

In 2014, UMass Amherst completed a project funded by the NEH’s Humanities Collections and Reference Resources grant program to digitize the papers of W.E.B. Du Bois in their entirety. Nearly 95,000 letters, books, essays, poems, photographs, and pieces of ephemera have been digitized and described at the item level and placed online through the UMass digital repository Credo. The content touches on the broad swath of American and African American history ranging from the era of Reconstruction through the rise of Jim Crow, the Pan-African movement and peace movement to the McCarthy era, and the dawning of the modern civil rights movement. Du Bois's pioneering sociological research sits side-by-side with drafts of his greatest work, The Souls of Black Folk. One can pore through correspondence relating to the Harlem Renaissance, the founding of the Niagara Movement and the NAACP, and the nascent movements for African liberation.

Scholars are already taking advantage of the online collection, which has exposed obscure connections and reaffirmed the global impact of Du Bois's ideas. From the Bahamas and Trinidad to Ghana and Nigeria, researchers have located correspondence linking Du Bois to movements for social justice in their countries, and a team in India discovered a brief but highly significant exchange between Du Bois and a key Dalit ("Untouchable") activist. In 1946, B.R. Ambedkar wrote Du Bois to express his solidarity with the struggle for racial equality in the United States, adding that he considered the study of the race problem in the United States "not only natural but necessary."

Closer to home, another researcher has demonstrated the persistence that enabled Du Bois to build and maintain ties among Historically Black Colleges and Universities, locating hundreds of letters with colleagues at Prairie View College, for example, that shed light on the politics of African American education at the time.

Nor has the impact of the online collection been restricted to scholarship. People have discovered letters from their ancestors to Du Bois that they never knew existed, and in one instance, a man discovered a letter he had written himself, but forgotten, remarking "I sounded pretty good for a freshman in college." Du Bois's nascent online presence has prompted others to donate previously unknown items to the collection, such as an image of the delegates to the 1906 convention of the Niagara Movement, which surfaced at a yard sale in Maryland.

“What we could not have anticipated was how the NEH project would open doors for other initiatives -- and we are seeing only the first wave,” says Robert Cox, Head of Special Collections and University Archives at UMass Amherst. The success of the NEH project helped secure additional funding from the National Historical Records and Papers Commission to digitize the complete papers of Horace Mann Bond, a correspondent of Du Bois's and a leader in civil rights and higher education for African Americans.

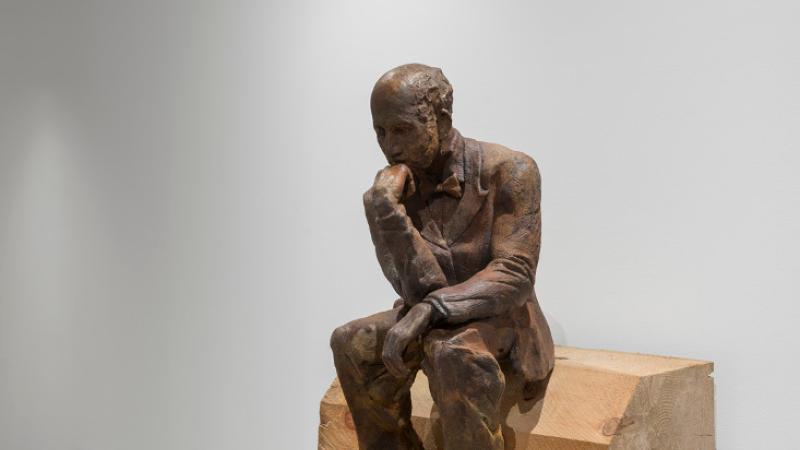

The digitized Du Bois Papers have also inspired contemporary artists. In 2013, the UMass Museum of Contemporary Art received an award from the National Endowment for the Arts to produce the exhibit Du Bois in Our Time. That project facilitated a conversation between ten artists and scholars in African American history, resulting in a series of challenging works of art that are, in effect, an aesthetic contribution to a modern rethinking of Du Bois.

The result has been a confluence of voices past and present, across borders real and imagined, present and future. Artists Radcliffe Bailey; Mary Evans; Brendan Fernandes; LaToya Ruby Frazier; Julie Mehretu; Ann Messner; Jefferson Pinder; Tim Rollins & KOS; Mickalene Thomas; and Carrie Mae Weems were inspired by Du Bois’s poetic writing, some by his early anticipation of the women’s rights and environmental movements, and his warnings against nuclear proliferation and other modern afflictions. All artworks in the exhibition were testaments to the inspiration and impact Du Bois has had on their lives and artistic practice.

Cox surmises that as the online collection attracts a new generation of scholars, artists, and the public to the expansive work and life of W.E.B. Du Bois, “many more will undoubtedly find inspiration in the groundwork Du Bois laid for movements in public dissent, while others will discover how problems he wrote about a century ago are still with us, and in certain cases more urgent than ever.”

Related Links

You can access the W.E.B. Du Bois Papers at: http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/collection/mums312.

You can view footage of the symposium, “Du Bois In Our Time,” hosted by UMass Contemporary Art Museum here.