From the Local to the Global: America’s Newspapers Chronicle the Struggle for Women’s Rights

Suffrage Hikers

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ggbain.12622

Suffrage Hikers

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ggbain.12622

On Election Day in 1920, millions of American women exercised their right to vote for the first time. For almost 100 years, women had been fighting for that right: they had fought their opponents, both men and women, logged thousands of miles, printed pamphlets, founded organizations, made speeches, and signed petitions, arguing that women, like men, deserved all of the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. The leaders of the movement did not always agree with each other and sometimes their disagreements threatened to derail their progress, but in the end, their commitment and sacrifice led to the enfranchisement of all American women. The milestones in women’s history discussed here come from searches of newspapers available on Chronicling America.

About Chronicling America

Chronicling America is a freely accessible web site providing information about and access to historic United States newspapers published between 1836 and 1922. The site is produced through the National Digital Newspaper Program, a partnership between the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and state projects. NEH awards support to state projects to select and digitize newspapers that represent the state’s historical, cultural, and geographic diversity, and to contribute essays containing background information about each paper’s editor and historical context. The Library of Congress unifies all content provided by states, and permanently maintains the digital information. Chronicling America is freely available to internet users everywhere. Users may search the millions of digitized pages contributed by state projects and the Library of Congress, and may consult a national newspaper directory to identify newspaper titles available in all types of formats. This effort ensures that users will continue to have access to this historical record, even as technology changes.

Seneca Falls Convention

Newspapers available through Chronicling America expose the rich texture of the women’s rights movement and its many milestones, meetings, and debates in a way that few other resources can. For example, in July 1848, early women’s rights advocates including Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton planned a two-day convention in Seneca Falls, New York, to discuss women’s role in society. Convention attendees prepared a “Declaration of Sentiments,” modeled on the Declaration of Independence, delineating the “civil, social, political, and religious rights” of women. After some debate, delegates decided to include in the declaration women’s suffrage—the right to vote. Some observers at the time were quite dismissive of the convention; a write-up in the Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania Jeffersonian Republican reported that “The women of Seneca Falls had a convention at which they put forth a ‘declaration of independence’ asserting that men and women were created equal. This being a leap year, the women have a perfect right to make ‘declarations’ of any descriptions without impunity.” Despite such mocking, the organizers held similar meetings over the next two years in Rochester, New York, and in Ohio, Indiana, and Pennsylvania. Many years later, a New York newspaper article reporting on the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, pointed to the foundation for women’s rights laid at Seneca Falls.

The West Advances the Right to Vote

Despite these early eastern efforts for women’s rights, it was in the West, that women first gained the right to vote. Wyoming was the first state to grant women full suffrage, in 1890, followed in quick succession by Colorado, Utah, and Idaho. In Utah, the Evening Dispatch reported, women’s suffrage “went into the constitution with a whoop.” Soon newspapers were debating the effects of woman suffrage. A 1894 article in the Kansas Agitator entitled “Wyoming Leads in Morals,” suggested that, because women in Wyoming had the right to vote, the state had a smaller ratio of criminals in the population than the “supposedly most civilized” northeastern states. According to the article, Wyoming’s improvement from its roots as “the most barbarous and murderous [place] on the continent” stemmed from the civilizing influence of women’s participation in public affairs. “The air of liberty,” stated the article, “breeds purity.” Contemporary observers attributed the early adoption of women’s suffrage in the western states to various factors, including the unconventional personalities of those who settled there, the need to attract women to an area populated primarily by men, or simply a ploy to solidify power by expanding the voter base.

The Reform Movement

In the West as in the East, the local press was often the mouthpiece for hashing out issues involving women’s rights. For example, Abigail Scott Duniway, known as “Oregon’s Mother of Equal Suffrage,” published The New Northwest in Portland from 1871 to 1887. Like many suffragists, Duniway advocated reforms beyond women’s enfranchisement, including temperance, wage equality, the right of women to own property, and the rights of Native Americans and Chinese immigrants. The New Northwest was “a journal for the people…not a women’s rights, but a human rights organ, devoted to whatever policy may be necessary to secure the greatest good for the greatest number.” One of its earliest battles was for economic rights for women. Until the passage of the Married Women’s Property Act of 1878 married women in Oregon had no property rights, and any wages women earned legally belonged to their husbands. In 1912, when Oregon became the seventh state to grant women suffrage, the state’s governor asked Duniway to draft and sign the equal suffrage proclamation.

Temperance

From the beginning, women’s suffrage was connected with the movement for temperance, and the two were intertwined in the public discussion of women’s rights. For some observers, this was a natural affiliation. Alice Stone Blackwell, a prominent journal editor, defended suffrage on many grounds, observing that it would increase the amount of “dry” territory in the United States and reduce the “power of the saloon in politics.” A critical article in the Ogden [Utah] Standard asked, on the other hand, “Is Woman’s Suffrage Throwing John Barleycorn?” The writer sought to separate the demand for suffrage from the prohibition of alcohol, pointing out that the earliest states to adopt woman suffrage, Wyoming and Utah, had not become dry decades after women got the right to vote there.

The Anti’s

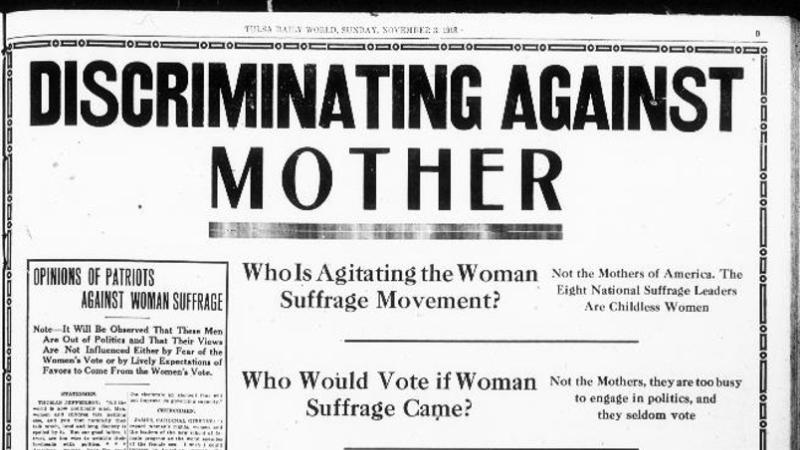

As the women’s rights movement gained momentum, so did opposition to suffrage. The New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, founded in 1897, asked “Why force women to vote?” Opponents ran the gamut politically, from conservatives who thought suffrage would undermine the family, to anarchists like Emma Goldman who claimed that it would lead to the legislation of morality, to progressives who feared suffrage in the West was a Mormon scheme or one to increase conservative voter bases. Accusing suffrage activists of “discriminating against the mother,” the Oklahoma Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage urged voters to “protect the family and vote ‘no’ on the Woman Suffrage Amendment.” The New York Evening World even claimed that equal suffrage had destroyed an entire town in New Jersey when women were allowed to hold elective office—although it is sparse on the precise details of the how the town’s undoing was the fault of women, other than that they had closed a number of saloons. Leading the movement was the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, whose proponents came to be known as the Anti’s.

Divorce and Women’s Rights

Although suffrage was a widely publicized issue, women’s rights extended beyond the vote to issues of property and self-determination—including divorce. For several decades, Indiana had one of the most liberal divorce laws in the country; the phrase “Indiana divorce” reflected the trend of people flocking to that state for a quick and easy divorce. While women’s rights advocates viewed the relative ease of divorce as a boon for women, enabling them to exit unhappy marriages, critics felt that divorce undermined society, and they connected liberalized divorce laws with women’s suffrage. The Weekly Arizona Miner declared that “the upshot of woman suffrage” was “free love and easy divorces,” leading to social ills including abolition of the family. “What a horrible mess of darkness, diabolism, and chaos, to be sure!” Under pressure from other states and public opinion, Indiana eventually reformed its divorce laws—but not before divorce was included in national debates about women’s rights.

Travels at Home

As many American women were meeting locally in town halls, others took to the road—both on foot and by car—to campaign for women’s rights. Known as “Suffrage Hikes,” between 1912 and 1914 these activities brought national attention to the issue of women's suffrage. Rosalie Gardiner Jones, known as “the General,” organized the first such hike. Some 200 women left from Manhattan on December 16, 1912, and continued through sun, rain, and snow, concluding their 170-mile journey twelve days later in Albany. Another hike in 1913 from New York City to Washington, D.C., covered 230 miles in 17 days. One of the best known of the women’s automobile tours was that of Alice Snitzer Burke and Nell Richardson, who set out from New York on April 6, 1916, in their suffrage car “The Golden Flyer,” with plans to cover 15,000 miles across the United States and back again (in the end, they totaled 10,700 miles). Stopping in towns along the way, their main destination was the National Woman’s Party Convention held in Chicago and St. Louis.

And Travels Abroad

Still other suffragists traveled abroad to learn from their peers in other countries (both Sweden and Norway had granted women the right to vote in the early years of the 20th century) and to assist women in countries where help was needed. Newspapers large and small reported on the foreign travels of Carrie Chapman Catt, a leader in the suffrage movement and founder of the League of Women Voters. In 1912, the Daily Missoulan in Montana recounted Catt’s attendance at the International Suffrage Convention, held in Stockholm in 1911. With the objective “to organize the whole world for woman suffrage,” Catt journeyed to Africa as well, delivering “hundreds of suffrage addresses under unique and novel conditions.” The newspaper reported that Catt went on to India, China, and Japan to establish affiliates of the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance (now known as the International Alliance of Women), of which she was then the president.

Things Heat Up: Picketing and Hunger Strikes

Galvanized by Illinois’ decision to allow women to vote for the President, in 1913 suffragists such as Alice Paul and Lucy Burns launched an aggressive campaign, using tactics of the militant wing of the British suffrage movement: picketing, petitioning, pageants, parades and demonstrations, hunger strikes, and imprisonment. Holding street meetings and distributing pamphlets, they shifted attention away from state voting rights and toward a federal suffrage amendment. Their tactics paid off, and by 1917, a tipping point had been reached. With the entry of the United States into what President Woodrow Wilson declared a “War for Democracy,” women who had been fighting for equal rights for years grew even more determined. On June 20, 1917, while the President was hosting Russian delegates in Washington, suffragists unfurled a banner comparing Wilson to the German Kaiser. Over the rest of the year, women organized demonstrations in front of the White House, and many were arrested and sentenced to time in jail. In October 1917, Alice Paul and some of her fellow demonstrators, calling themselves political prisoners, organized a hunger strike, which spread to Washington, D.C.-area workhouses. The protests culminated in what is known as “The Night of Terror” (November 10, 1917), a confrontation between jailed protesters and prison guards at the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia. Hunger strikes and women being beaten by police proved an embarrassment for the President, and in 1918, Wilson announced that he would support suffrage for women. A year later, the 19th Amendment was passed, prohibiting the denial of voting rights on the basis of sex. The Amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920, and became law.

Want to Learn More?

The links contained here merely scratch the surface of fascinating primary source material in historic newspapers, which are a boon for studying history first hand. How can you use the nearly 7 million pages and 1,100 titles in the Chronicling America site?

- The Library of Congress’s list of Topics in Chronicling America is a great way to get started searching. The topic page for The Nineteenth Amendment (votes for women), for example, contains important dates, suggested search terms, and sample articles.

- Search by keyword, or use the Advanced Search to narrow your search by state, newspaper title, or date. For women’s history, try terms like “suffrage,” and “suffragist,” or combine “women” and “vote” in the search field. You can also look for more specific information about organizations like the National Women Suffrage Association and names like Alice Paul, Lucretia Mott, and Abigail Duniway.

- Check out the short historical essays accompanying the home page for each newspaper. These essays contain interesting information about the paper’s editors, political affiliations, and points of view. The essay for The New Northwest explains Editor Abigail Scott Duniway’s background and point of view and the paper’s place in history.

- You can also search the newspapers published by specific groups. Using the pull-down menu on the All Digitized Newspapers tab, browse African American, Native American, Irish, Jewish, Mexican, Latin American, and other groups’ publications.

- NEH’s EDSITEment initiative has added a Chronicling America portal, containing resources for searching the database and using newspapers in the classroom.

A related resource is the Library of Congress’s American Memory project, where you can find photographs, sound recordings, maps, prints, and other documents of the American experience. The American Women collection contains materials on women’s history.