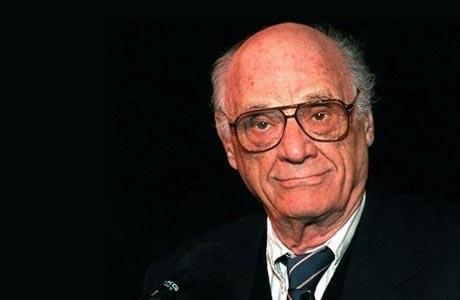

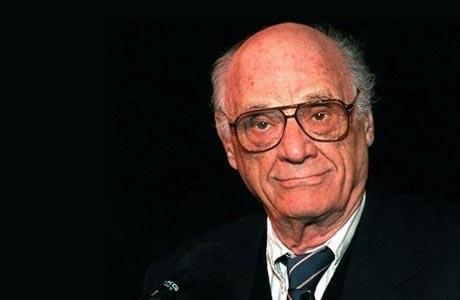

Arthur Miller

Jefferson Lecture

2001

"The American Dream is the largely unacknowledged screen in front of which all American writing plays itself out," Arthur Miller has said. "Whoever is writing in the United States is using the American Dream as an ironical pole of his story. People elsewhere tend to accept, to a far greater degree anyway, that the conditions of life are hostile to man's pretensions." In Miller's more than thirty plays, which have won him a Pulitzer Prize and multiple Tony Awards, he puts in question "death and betrayal and injustice and how we are to account for this little life of ours."

For nearly six decades, Miller has been creating characters that wrestle with power conflicts, personal and social responsibility, the repercussions of past actions, and the twin poles of guilt and hope. In his writing and in his role in public life, Miller articulates his profound political and moral convictions. He once said he thought theater could "change the world." The Crucible, which premiered in 1953, is a fictionalization of the Salem witch-hunts of 1692, but it also deals in an allegorical manner with the House Un-American Activities Committee. In a note to the play, Miller writes, "A political policy is equated with moral right, and opposition to it with diabolical malevolence." Dealing as it did with highly charged current events, the play received unfavorable reviews and Miller was cold-shouldered by many colleagues. When the political situation shifted, Death of a Salesman went on to become Miller's most celebrated and most produced play, which he directed at the People's Art Theatre in Beijing in 1983.

A modern tragedian, Miller says he looks to the Greeks for inspiration, particularly Sophocles. "I think the tragic feeling is evoked in us when we are in the presence of a character who is ready to lay down his life, if need be, to secure one thing-his sense of personal dignity," Miller writes. "From Orestes to Hamlet, Medea to Macbeth, the underlying struggle is that of the individual attempting to gain his 'rightful' position in his society." Miller considers the common man "as apt a subject for tragedy in its highest sense as kings were." Death of a Salesman, which opened in 1949, tells the story of Willy Loman, an aging salesman who makes his way "on a smile and a shoeshine." Miller lifts Willy's illusions and failures, his anguish and his family relationships, to the scale of a tragic hero. The fear of being displaced or having our image of what and who we are destroyed is best known to the common man, Miller believes. "It is time that we, who are without kings, took up this bright thread of our history and followed it to the only place it can possibly lead in our time-the heart and spirit of the average man."

Arthur Asher Miller, the son of a women's clothing company owner, was born in 1915 in New York City. His father lost his business in the Depression and the family was forced to move to a smaller home in Brooklyn. After graduating from high school, Miller worked jobs ranging from radio singer to truck driver to clerk in an automobile-parts warehouse. Miller began writing plays as a student at the University of Michigan, joining the Federal Theater Project in New York City after he received his degree. His first Broadway play, The Man Who Had All the Luck, opened in 1944 and his next play, All My Sons, received the Drama Critics' Circle Award. His 1949 Death of a Salesman won the Pulitzer Prize. In 1956 and 1957, Miller was subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee and was convicted of contempt of Congress for his refusal to identify writers believed to hold Communist sympathies. The following year, the United States Court of Appeals overturned the conviction. In 1959 the National Institute of Arts and Letters awarded him the Gold Medal for Drama. Miller has been married three times: to Mary Grace Slattery in 1940, Marilyn Monroe in 1956, and photographer Inge Morath in 1962, with whom he lives in Connecticut. He and Inge have a daughter, Rebecca. Among his works are A View from the Bridge, The Misfits, After the Fall, Incident at Vichy, The Price, The American Clock, Broken Glass, Mr. Peters' Connections, and Timebends, his autobiography. Miller's writing has earned him a lifetime of honors, including the Pulitzer Prize, seven Tony Awards, two Drama Critics Circle Awards, an Obie, an Olivier, the John F. Kennedy Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Dorothy and Lillian Gish prize. He holds honorary doctorate degrees from Oxford University and Harvard University.

Throughout his life and work, Miller has remained socially engaged and has written with conscience, clarity, and compassion. As Chris Keller says to his mother in All My Sons, "Once and for all you must know that there's a universe of people outside, and you're responsible to it." Miller's work is infused with his sense of responsibility to humanity and to his audience. "The playwright is nothing without his audience," he writes. "He is one of the audience who happens to know how to speak."

The Playwright Living In The Present Tense

BY JAMES HOUGHTON

Sitting atop a Manhattan apartment building in a community garden lush with flowers marked the beginning of a relationship with Arthur Miller that opened my eyes and heart to a vista of possibilities I had not imagined.

Now, we all know that Arthur Miller has had an extraordinary life. You can read about his work in this very magazine or better yet, pick up any one of his many plays, essays, or short stories, or perhaps his autobiography. We also understand that Arthur is highly regarded for his intellectual, cultural, and political contributions to our country and beyond. Some might recognize his good taste or know a bit about his carpentry skills and his passion for making practical furniture. Perhaps it is his relentless activism that strikes a chord with you. Maybe you have heard a thing or two about his travels around the world and his relationship with various leaders across the globe. Friends might note his family, his laps in his pond, or the grandchild that tickles him. Maybe it is the sweet ditty he wrote, "Sittin' Around," from The American Clock, one of my favorites.

I suspect you have an inkling of the remarkable decades of experiences he has lived through and affected. The Great Depression comes to mind, or say, the McCarthy era? Perhaps the civil rights struggle or the too-frequent assassinations. Maybe the great jazz or big band era. The golden ages of radio, television, film, and, some would say, theater. Watergate? Cuba? The construction and destruction of the Berlin Wall? Maybe World War II, Korea, or Vietnam? The Holocaust? The rise and fall of so many governments, democracies, peoples--you get the idea.

The whirlwind of history through which Arthur has passed is nothing less than tremendous, but what distinguishes him from others is that his passions have insistently pushed him to note time. He has been compelled to remember our past, and by not forgetting, to inform our future. But what strikes me most about him is his absolute insistence on living life in the present tense.

Living is something that Arthur does extremely well. Through each decade of his astonishing life, he has managed to be deeply touched and to have deeply touched many. His intellect is extraordinary, his wisdom cup full, his heart swollen to capacity, and his spirit is that of a shy, six-year-old kid trying not to let on.

One of my great pleasures in recent years has been to nudge Arthur about that deep well of optimism I know lies within him. I usually get a good laugh out of him when I warn him that he might be in danger of exposing that neatly covered reservoir. You see, I believe Arthur Miller is a dreamer and seeker of truth--the truth that lies within the mystery of human existence. He seeks the truth and dares to ask the questions Why am I here? How can I make a difference? Who am I? What am I? The big stuff. By merely asking these questions--let alone pursuing cogent answers--Arthur reveals the optimist living within him. No one makes it through the last eighty-five years standing without a pillar of optimism to hold him up in the face of disappointment. Arthur Miller, not only are you an optimist, but a cheery one at that. Sorry, Arthur. Your cover is blown.

Perhaps most profound for me is Arthur's willingness to embrace his own fear. Fear--the common denominator for all of us. If there is a single gift that my friendship with Arthur has bestowed, it has been the demystification of fear.

Let me go back for a minute to that rooftop in Manhattan. I remember sitting across from Arthur that breezy spring day. We were there to talk about working together at my theater, Signature Theatre Company, where each year we have the pleasure of dedicating a season to a living writer. Arthur and I started by discussing each and every one of his plays and the various experiences associated with his canon. The work began to tell us what might be a meaningful season, as it always does when it's good. We talked not of his works known by many, but rather, the plays that held a special place in Arthur's heart. Some cried out for mending, some just for another chance, but all fed the spirit of discovery in both of us. As we talked, that kid inside Arthur surfaced. His eyes lit up as the ideas percolated.

We talked of putting together a season that would address those "I wish I could reinvent" or "if I had to do it over again" moments we have in our lives. It was quite a joy to give birth to the renewed potential in each play and in doing so, to present a broader, deeper experience and appreciation of Arthur's work-and to have Arthur involved in every step of the discovery.

Our conversation ultimately resulted in a 1997-1998 season that included a reworking of The American Clock, The Last Yankee with I Can't Remember Anything, and the world premiere of Mr. Peters' Connections. In addition, the season presented a live broadcast of a radio play from the late thirties, The Pussycat and Expert Plumber Who Was a Man; and a reading by Arthur of his children's story, Jane's Blanket, which he read to a crowd of children and his now-grown daughter, Jane.

That season I had the pleasure of seeing Arthur at work-an artist who is completely in tune with his craft and, most importantly, who is understanding and respectful of his collaborators. He was always available and ready to expose the mystery of the creative moment, either by his willingness to accept newly discovered subtext, or by acknowledging the wonder of the creative process itself. No pretense . . . no bull . . . straight out. He gave life to his work by allowing it to breathe and evolve through respectful collaboration.

There was a fun moment when we were in rehearsal for The American Clock, a Depression-era tale that confronts the impact and toll of the time. It is a bit of a monster with fifteen actors playing some fifty roles and over thirty songs from the period played live. It's a big one. We were in the first week of rehearsal, breaking down the text and trying to get all the circumstances of the play in place, organizing the facts. I remember one of the actors had pointed out a discrepancy in the text to Arthur--two facts that that could not have occurred simultaneously. The room fell silent as Arthur contemplated this discovery. He turned to the actor and with great authority and a devilish grin said, "Mind your own business." He was caught . . . and so were we all, by his honesty and good humor. It seems a simple thing, I suppose, to witness someone "fessing up," but somehow the stakes seem higher when you are sitting in the room with one of the finest writers and minds of the twentieth century.

Toward the end of our season I sat with Arthur at the opening of his new play, Mr. Peters' Connections. We sat out in the lobby, both having opted to enjoy the peace of an empty room over the tension of an audience surely judging our every move. He turned to me and said, referring to our audience, "Where do they come from? Who are they? Why do they come?" There was a sort of puzzlement, or anxiety--or could it be fear--that ran across Arthur's face in that moment, a revealing reflection of my own state of mind.

Those questions got me thinking and ultimately I realized that if we are to learn anything about ourselves, we must be willing to be afraid, to step forward into the abyss of uncertainty. Arthur's willingness to expose his own doubts and fears was an invitation for me to forgive my own. Surely, I thought, he has been at this a long time and doesn't feel what I feel. But of course he must. Arthur, by example, provided me with a great gift that day, liberating me from expectation and the grip of fear.

I realized in my time with Arthur that experience informs the present, but does not provide answers. Although we all hope for a clear path to take us wherever we think it should, remarkably, we realize there is no such thing. Here is Arthur Miller, playwright, intellectual, activist, etc. He must have it figured out, right? Wrong. What he has is the willingness to say, "I don't know," and to muster up enough courage to proceed, one foot in front of the other. He confronts his fear every day and runs straight at it, full speed ahead. Time has told him that there is no other choice worth pursuing if you are to live in the present tense. The final punch is that while our past informs our present, both are irrelevant unless we have the courage to "know" nothing--to approach the present as if it were the first time. After all, isn't it?

Fear is a powerful tool when someone teaches you how to use it. Courage is contagious when you see the good it does and how it liberates you. Both, together, open your eyes and heart to a vista of possibilities previously unimagined. The "kid" that is present in Arthur is the fear itself. It is his wonder at humanity and his astonishment that we ever connect to one another at all. He has managed, for all his years, to hold on to wonder, embrace fear, and challenge himself and a few others along the way. That is some remarkable kid.

James Houghton is the founder and artistic director of New York's Signature Theatre Company, which devotes each season to the works of one living writer. The 1997-1998 season featured Arthur Miller as a Playwright-in-Residence.

The Poet: Chronicler of The Age

BY CHRISTOPHER BIGSBY

Arthur Miller once observed that in America a poet is seen as being “like a barber trying to erect a sky scraper.” He is, in other words, regarded as being “of no consequence.” Miller is so often praised, and occasionally decried, for what is taken to be his realism—a realism expressed through the authentic prose of a salesman, a longshoreman, a businessman. But Arthur Miller is no simple realist and hasn’t been for fifty years. Moreover, he is incontestably a poet: one who sees the private and public worlds as one, who is a chronicler of the age and a creator of metaphors.

In an essay on realism written in 1997, Miller made a remark that I find compellingly interesting. “Willy Loman,” he said, “is not a real person. He is if I may say so a figure in a poem.” That poem is not simply the language he or the other characters speak, though this is shaped, charged with a muted eloquence of a kind which he has said was not uncommon in their class half a century or more ago. Nor is it purely a product of the stage metaphors which, like Tennessee Williams, he presents as correlatives of the actions he elaborates. The poem is the play itself and hence the language, the mise en scène, the characters who glimpse the lyricism of a life too easily ensnared in the prosaic, a life which aspires to metaphoric force.

Willy Loman a figure in the poem? What kind of a figure? A metaphor. A metaphor is the meeting point of disparate elements brought together to create meaning. Willy Loman’s life is just such a meeting point, containing, as it does, the contradictions of a culture whose dream of possibility has foundered on the banality of its actualization, a culture that has lost its vision of transcendence, earthing its aspirations so severely in the material world. As Miller has said of Willy’s speech when he confronts his employer Howard, a speech he rightly calls an “aria,” “What we have is the story of a vanished era, part real, part imaginary, the disappearing American dream of mutuality and in its place the terrible industrial process that discards people like used-up objects. And to me this is poetic and it is realism both.” Much the same could be said of the rest of his work. It grows out of an awareness of the actual, but that actuality is reshaped, charged with a significance that lifts it into a different sphere.

But let’s, very briefly, look at some of the component elements that shape Arthur Miller’s poetry in Death of a Salesman. In a notebook he once remarked that “there is a warehouse of scenery in a telling descriptive line.” So there is. Consider the opening stage direction to Act 1, an act, incidentally, that has a bracketed subtitle, “An Overture,” and which begins with music. The description, the first words of the text, is at once descriptive and metaphoric. “A melody,” we are told, “is heard, playing upon a flute. It is small and fine, telling of grass and trees and the horizon.” This is something of a challenge to a composer, but what follows is equally a challenge to a designer as he describes a house that is simultaneously real and imagined, a blend of fact and memory that precisely mirrors the frame of mind of its protagonist and the nature of the dreams that he seeks, Gatsby-like, to embrace.

In other words, both in terms of music and stage set, we are dealing immediately with the real and with a poetic image, with a poet’s gesture, and that is how it was seen by a young Lanford Wilson who, in 1955, saw a student production. It was, he has said, “The most magical thing I’d ever seen in my life . . . the clothesline from the old building all around the house gradually faded into big, huge beech trees. I nearly collapsed. It was the most extraordinary scenic effect and, of course, I was hooked on theater from that moment….That magic was what I was always drawn to.” And as yet, of course, not a word of the text has been spoken, though a great deal has been communicated as the real has been transmuted into symbol. Incidentally, an astonishing number of playwrights have acknowledged this play as central to them. Tony Kushner was drawn to the theater by watching his mother perform in it. David Rabe virtually borrows lines from it in Sticks and Bones, Lorraine Hansberry acknowledged its influence on A Raisin in the Sun while Adrienne Kennedy has confessed to constantly rereading it and keeping a notebook of Miller’s remarks about theater. Tom Stoppard saw Salesman as a major influence on his first play while Vaclav Havel has likewise acknowledged its inspirational power. But for the moment let’s stay with the set.

As Miller said in the notebook he kept while writing Salesman, “Modern life has broken out of the living room. Just as it was impossible for Shakespeare to say his piece in the confines of a church, so today Shaw’s living room is an anachronism. The object of scene design ought not to reference a locale but to raise it into a significant statement.”

The original stage direction indicated of the Loman house that “it had once been surrounded by open country, but it was now hemmed in with apartment houses. Trees that used to shade the house against the open sky and hot summer sun were for the most part dead or dying.” Jo Mielziner’s job, as designer and lighting engineer, was to realize this in practical terms, but it is already clear from Miller’s description that the set is offered as a metaphor, a visual marker of social and psychological change. It is not only the house that has lost its protection, witnessed the closing down of space, not only the trees that are withering away and dying with the passage of time. It is a version of America. It is human possibility. It is Willy Loman.

Other designers have come up with other solutions to the play’s challenges, as they have to Mielziner’s use of back-lit unbleached muslin, on which the surrounding tenement buildings were painted and which could therefore be made to appear and disappear at will. Other designers have found equivalents to his use of projection units that surround the Loman house with trees whose spring leaves would stand as a reminder of the springtime of Willy’s life—-at least as recalled by a man determined to romanticize a past when, he likes to believe, all was well with his life.

Fran Thompson, designer of London’s National Theatre production in 1996, chose to create an open space with a tree at center stage, but a tree whose trunk had been sawn through leaving a section missing, the tree being no more literal and no less substantial than Willy’s memories.

And, indeed, it is the fact that for the most part this is a play that takes place in the mind and memory of its central character that determines its form, as past and present interact in his mind, linked together by visual, verbal, or aural rhymes. In the National Theatre production, all characters remained on stage throughout, being animated when they moved into the forefront of Willy’s troubled mind, or swung into view on a revolve. In other words, the space, while literal, was simultaneously an image of a mind haunted by memories, seeking connections.

Meanwhile, despite his emphasis on “the actual” and “the real,” the language of Death of a Salesman is not simply the transcribed speech of 1930s Brooklyn. Though its author is aware that all speech has its particular rhythms, he is aware, too, that, as he has said, “the Lomans have gotten accustomed to elevating their way of speaking.” “Attention, attention must be finally paid to such a person,” was not, as Mary McCarthy and others thought, an inadvertent revelation of a concealed Jewish identity, but Miller’s deliberate attempt to underscore the exemplary significance of Willy Loman. For, as he said, “Prose is the language of family relations; it is the inclusion of the larger world beyond that naturally opens a play to the poetic.” And, indeed, Linda’s despairing cry is that of a wife claiming significance for a desperate husband abandoned by those whose opinions he values, as it is also that of a woman acknowledging that that husband is the embodiment of other suffering human beings.

And if Miller was right in saying that “in the theater the poetic does not depend, at least not wholly, on poetic language,” there is no doubt that the poetic change to his language is carefully worked for. And which playwright, American or European, has offered such a range of different varieties of speech: a Brooklyn longshoreman, a seventeenth-century farmer, a Yankee carpenter, each authentic, but each so shaped so that there are moments when it sings. Turn to the notebooks which he kept while writing The Crucible and you will find a number of speeches tried out first in verse. Here is one of them.

We have exalted charity over malice

Suspicion above trust

We have hung husbands for loyalty

To wives, and honored traitors to their families

And now even the fields complain.

There will be hunger in Massachusetts

This winter the plowman is busy

Spying on his brother, and the earth

Gone to seed. A wilderness of weeds

Is claiming the pastures of our world

We starve for a little charity.

. . . nothing will grow but dead things.

Even in Death of a Salesman, Charley’s final speech was first tried out in a loose free verse.

All you know [is] that on good days or bad,

You gotta come in cheerful.

No calamity must be permitted to break through

Cause one thing, always you’re a man who’s gotta be liked.

You’re way out there riding on a smile and a shoeshine

And when they start not smilin’ back,

It’s the big catastrophe. And then you get

A couple of spots on your hat, and you’re finished

Cause there’s no rock bottom to your life.

In the final version it loses its free verse form and its redundancies but retains its lyrical charge. The tension in the prose, the rhythms, the images, meanwhile, were born out of a poetic imagination. It is spoken in prose, but a prose charged with the poetic.

If Willy Loman was a figure in a poem, that is even more true of the pseudonymous character in Miller’s later play, Mr. Peters’ Connections, set in what the opening stage direction calls “A broken structure indicating an old abandoned night club in New York City.” But that stage direction is itself metaphoric, for it is not the setting alone that is a “broken structure.” It is, potentially, a life. And if this play is a poem it is, in part, an elegy, an elegy for an individual but also, in some senses, for a culture, for a century, indeed for human existence itself.

For as he said the questions theater tries to address are “death and betrayal and injustice and how we are to account for this little life of ours.” In a sense these are the subjects of Mr. Peters’ Connections, though it is not a play that ends in despair.

It is a play that laments the loss of youth, the stilling of urgencies, and the dulling of intensity, as love, ambition, and utopian dreams devolve into little more than habit and routine. It is a play about loss—-the loss of those connections that once seemed so self-evident as moment led to moment, as relationships gave birth to their own meaning, as the contingent event shaped itself into coherent plot, as the fact of the journey implied a purposeful direction and a desirable destination. It is about a deracinated man; literally, a man who has lost his sense of roots, his connections. In another sense it is a contemplation of life itself, whose intensity and coherence slowly fades, whose paradox can never finally be resolved, as it is also a confrontation with death.

The conversations that constitute Mr. Peters’ Connections are the visions of a man in that half-world between wakefulness and sleep for whom life drifts away, becomes a jumble of half-forgotten people, incomplete stories. One by one he summons those with whom he has shared his life, but he encounters them first as strangers, as if they had already passed beyond the sphere in which he exists. A one-time lover, a brother, a daughter appear and disappear, but he can never quite recall what they were to him or he to them. In some senses their identity doesn’t matter. Yet he knows they must hold a clue to the meaning of his existence. The question is, what did he derive from them? What was important? What was the subject?

For Willy Loman, meaning always lay in the future. His life was “kind of temporary” as he awaited the return of his father, Godot-like, to flood his life with meaning, or as he projected a dream of tomorrow that would redeem his empty and troubling present. In Mr. Peters’ Connections meaning lies not in the future but in the past, in memories that even now are dulling like the embers of a once-bright fire, in the lives of those others who, in dying, take with them pieces of the jigsaw, fragments of the world where clarity of outline has been a product of shared assumptions and mutual apprehensions. What happens, he implicitly asks himself, to our sense of ourselves and the world, when one by one our fellow witnesses withdraw their corroboration, when there is nobody to say, “Yes, that’s the way it was, that’s who you once were.” As they die and withdraw from the stage, they take incremental elements of meaning with them and gradually thin his sense of the real to transparency.

In a sense Mr. Peters’ Connections is not set anywhere. The night club had once been a cafeteria, a library, a bank, its function shifting as the supposed solidities of the past dissolve. In a way, compacted into this place is the history of New York, the history of a culture and of a man. It exists in the emotional memory of its protagonist.

The word “connections” refers not only to Mr. Peters’ links with other people, particularly those closest to him, but also to his desire to discover the relationship between the past and the present, between a simple event and the meaning of that event. In other words, he is in search of a coherence that will justify life to itself. In facing the fact of death he is forced to ask himself what life has meant, what has been its subject. In that context the following is a key speech and one in which I find a justification for Miller’s own approach to drama as well as to the process of living, which that drama both explores and celebrates: “I do enjoy the movies, but every so often I wonder, ‘what was the subject of the picture?’ I think that’s what I’m trying to . . . to . . . find my connection with is . . . what’s the word . . . continuity . . . yes with the past, perhaps . . . in the hope of finding a . . . yes, a subject. That’s the idea I think.” In other words, the simplest of questions remains the most necessary of questions: “What is it all for?”

Fifty years ago, in the notebook he kept while writing Death of a Salesman, Miller wrote the following: “Life is formless . . . its interconnections are concealed by lapses of time, by events occurring in separated places, by the hiatus of memory. . . . Art suggests or makes these interconnections palpable. Form is the tension of these interconnections, man with man, man with the past and present environment. The drama at its best is the mass experience of this tension.” Death of a Salesman was concerned with that and generated a form commensurate with its subject. Much the same could be said of Mr. Peters’ Connections.

It is tempting to see a relationship between the protagonist and his creator. Mr. Peters recalls a time of mutuality and trust, a time when the war against fascism gave people a sense of shared endeavor. Once, he recalls, his generation believed in “saving the world.” “What’s begun to haunt me,” he explains, “is that next to nothing I believed has turned out to be true. Russia, China, and very often America. . . .” In a conversation three years ago with Vaclav Havel, Miller himself remarked, “I am a deeply political person; I became that way because of the time I grew up in, which was the Fascist period. . . . I thought . . . that Hitler . . . might well dominate Europe, and maybe even have a tremendous effect on America, and I couldn’t imagine having an audience in the theater for two hours and not trying to enlist them in some spiritual resistance to this awful thing.” Later, when China went communist, he set himself to oppose McCarthyism. He once confessed that he had thought theater could “change the world.” Today, like Mr. Peters, he is, perhaps, less sure of such an easy redemption.

If in some senses Mr. Peters is contemplating death, there is more than one form of dying. The loss of vision, of a sense of transcendent values, of purpose—what he calls a subject—is another form of death, operative equally on the metaphysical, social, and personal level. As Peters remarks, “Most of the founding fathers were all Deists . . . they believed that God had wound up the world like a clock and then disappeared. We are unwinding now, the ticks further and further apart. So instead of tick-tick-tick-tick we’ve got tick (pause) tick (pause) tick. And we get bored between ticks, and boredom is a form of dying.” The answer, perhaps, lies in a realization on that there is no hierarchy of meaning. As another character tells him, “Everything is relevant! You are trying to pick and choose what is important . . . like a batter waiting for a ball he can hit. But what if you have to happily swing at everything they thrust at you?” In other words, perhaps one can do no more than live with intensity, acknowledge the simultaneous necessity for and vulnerability of those connections without which there is neither private meaning nor public morality.

Willy Loman believed that the meaning of his life was external to himself, blind to the fact that he already contained that meaning, blind to the love of his wife and son. Mr. Peters comes to understand that his life, too, is its meaning, his connections are what justifies that life. This play, then, is not about a man ready to run down the curtain, to succumb to the attraction of oblivion. He may not rage against the dying of the light, but he does still find a reason to resist the blandishments of the night. So it is that Mr. Peters, a former airline pilot, remarks that “When you’ve flown into hundreds of gorgeous sunsets, you want them to go on forever and hold off the darkness.”

What is the poem? It is Mr. Peters’ life, as it is the play itself which mimics, symbolizes, and offers a metaphor for that search for coherence and meaning that is equally the purpose of art and the essence of life.

Willem de Kooning has spoken of the burden that Americanness places on the American artist. That burden seems to be, at least in part, a desire to capture the culture whole, to find an image commensurate with the size and nature of its ambitions, its dreams, and its flawed utopianism-—whether it be Melville trying to harpoon a society in search of its own meaning, Dreiser convinced that the accumulation of detail will edge him closer to truth, or John Dos Passos offering to throw light on the U.S. by means of the multiple viewpoints of modernism.

A big country demands big books. James Michener tried to tackle it state by state, with a preference for the larger ones. Gore Vidal worked his way diachronically, president by president, in books which if strung together would run into thousands of pages and in which he hoped to tell the unauthorized biography of a society. Henry James called the novel a great baggy monster and that is what it has proved to be in the hands of American novelists. Even America’s poets, from Whitman through to Ashbery, have shown a fondness for the epic.

The dramatist inhabits an altogether different world. He or she is limited, particularly in the modern theater, to no more than a couple of hours. (Unless your name is Eugene O’Neill, whose Strange Interlude ran for six hours, including a dinner break.) Increasingly, indeed, the dramatist is limited as to the number of actors he can deploy and the number of sets he can call for. The theater, of course, is quite capable of turning the few into many and a single location into multiple settings but the pressure is toward concision. The 800-page book becomes a 100-page play text. The pressure, in other words, is toward a kind of poetry, not the poetry of Christopher Fry or T. S. Eliot, but a poetry generated out of metaphor, a language without excess, a language to be transmuted into physical form, the word made flesh. Miller collapses the history of his society into the lives of his characters and in doing so, exemplifies a truth adumbrated by Ralph Waldo Emerson a century and a half ago when he said, “We are always coming up with the emphatic facts of history in our private experience and verifying them here . . . in other words there is properly no history, only biography.” Miller does not need 800 pages. He captures the history of a culture, indeed human existence itself, in the life of an individual; indeed in a single stage direction.

At the beginning of Death of a Salesman, Willy Loman enters carrying two suitcases. It takes the whole play—-and him, a lifetime—-to realize that they are not just the marks of his calling. They are the burden of his life, a life that he will lay down not just for his sons, but for a faith as powerful and all-consuming as any that has ever generated misguided martyrs. Staring into the future, in his present, he carries the burden of the past. He is, for a moment, the compacted history of a people, the embodiment of a myth, a figure in a poem: the poem of America, with its thousand points of light, its New Eden, its city on a hill, its manifest destiny. Here, distilled in a single stage image, is the essence of a whole culture still clinging to a faith that movement equals progress, selling itself a dream that accepts that personal and national identity are a deferred project, and that tomorrow will bring epiphany, revelation.

Willy Loman had all the wrong dreams, but they were a country’s dreams instilled into him out there in the heartland where his father, also a salesman, set out on that endless American journey into possibility, unmindful of those he abandoned, his eyes on the prize; a moment never forgotten by his son who constantly hears the sound of the flutes his father made and sold. For those who watch his dilemma, that sound, like the shrinking space around the Loman home, as a subtle light change takes us from past to present, recalls hope and betrayal in the same instant, in a compacted metaphor, the hope and betrayal seen by America’s writers from Cooper and Twain to Fitzgerald and beyond.

The subtitle of Death of a Salesman is Certain Private Conversations in Two Acts and a Requiem. Those private conversations are conducted in Willy Loman’s mind, but they are also America’s conversation with itself. Fifty years later, in Mr. Peters’ Connections, comes another such series of conversations as a man looks back over his life and wonders what it may have amounted to, what connections there are between people, between event and consequence, between the present and the past that it contains. He, too, is a figure in a poem. The poem is his life and he its author, but not he alone, for, as virtually all of Miller’s plays suggest, meaning is not something that will one day cohere. It is not an ultimate revelation. It is not contained within the sensibility of an isolated self. It lies in the connections between people, between actions and their effects, between then and now. The true poetry is that which springs into being as individuals acknowledge responsibility not for themselves alone, but for the world they conspire in creating and for those with whom they share past and present. The poetry that Arthur Miller writes and the poetry that he celebrates is the miracle of human life, in all its bewilderments, its betrayals, its denials, but, finally, and most significantly, its transcendent worth.

Christopher Bigsby is professor of American studies at the University of East Anglia, in Norwich, England, and director of the Arthur Miller Centre. His more than twenty-five books include Contemporary American Dramatists, The Cambridge History of American Theatre, The Cambridge Companion to Arthur Miller, and three novels.

The Crucible

John Proctor’s House.

HALE: Mary Warren, a needle have been found inside this poppet.

MARY WARREN, bewildered: Why I meant no harm by it, sir.

PROCTOR, quickly: You stuck that needle in yourself?

MARY WARREN: I--I believe I did, sir I--

PROCTOR, to Hale: What say you now?

HALE, watching Mary Warren closely: Child, you are certain this be your natural memory? May it be, perhaps that someone conjures you even now to say this?

MARY WARREN: Conjures me? Why no sir, I am entirely myself, I think. Let you ask Susanna Walcott—-she saw me sewin’ it in court. Or better still: Ask Abby, Abby sat beside me when I made it.

PROCTOR, to Hale and Cheever: Bid him begone. Your mind is surely settled now. Bid him out, Mr. Hale.

ELIZABETH: What signifies a needle?

HALE: Mary—-you charge a cold and cruel murder on Abigail.

MARY WARREN: Murder! I charge no—-

HALE: Abigail was stabbed tonight; a needle were found stuck into her belly—-

ELIZABETH: And she charges me?

HALE: Aye.

ELIZABETH, her breath knocked out: Why—-! The girl is murder! She must be ripped out of the world!

CHEEVER, pointing at Elizabeth: You’ve heard that, sir! Ripped out of the world! Herrick, you heard it!

PROCTOR, suddenly snatching the warrant out of Cheever’s hands: Out with you.

CHEEVER, Proctor, you dare not touch the warrant.

PROCTOR, ripping the warrant: Out with you!

CHEEVER: You’ve ripped the Deputy Governor’s warrant, man!

PROCTOR: Damn the Deputy Governor! Out of my House!

HALE: Now, Proctor, Proctor!

PROCTOR: Get y’gone with them! You are a broken minister.

HALE: Proctor, if she is innocent, the court—-

PROCTOR: If she is innocent! Why do you never wonder if Parris be innocent, or Abigail? Is the accuser always holy now? Were they born this morning as clean as God’s fingers? I’ll tell you what’s walking Salem—-vengeance is walking Salem. We are what we always were in Salem, but now the little crazy children are jangling the keys of the kingdom, and common vengeance writes the law! This warrant’s vengeance! I’ll not give my wife to vengeance!

THE CRUCIBLE opened in 1953 at the Martin Beck. © Arthur Miller 1952, reprinted with permission.

ALL MY SONS

The Kellers’ backyard.

KELLER: Listen, you do like I did and you’ll be all right. The day I come home, I got out of my car;—but not in front of the house . . . on the corner. You should’ve been here, Annie, and you too, Chris; you’d-a seen something. Everybody knew I was getting out that day; the porches were loaded. Picture it now; none of them believed I was innocent. The story was, I pulled a fast one getting myself exonerated. So I get out of my car, and I walk down the street. But very slow. And with a smile. The beast! I was the beast; the guy who sold cracked cylinder heads to the Army Air Force; the guy who made twenty-one P-40’s crash in Australia. Kid, walkin’ down the street that day I was guilty as hell. Except I wasn’t, and there was a court paper in my pocket to prove I wasn’t, and I walked . . . past . . . the porches. Result? Fourteen months later I had one of the best shops in the state again, a respected man again; bigger than ever.

CHRIS with admiration: Joe McGuts.

KELLER: now with great force: That’s the only way you lick ‘em is guts!

ALL MY SONS opened in 1947 at the Coronet Theater. © Arthur Miller 1947, reprinted with permission.

DEATH OF A SALESMAN

Howard’s Office.

WILLY, desperately: Just let me tell you a story, Howard—

HOWARD: ’Cause you gotta admit, business is business.

WILLY, angrily: Business is definitely business, but just listen for a minute. You don't understand this. When I was a boy—eighteen, nineteen— I was already on the road. And there was a question in my mind as to whether selling had a future for me. Because in those days I had a yearning to go to Alaska. See, there were three gold strikes in one month in Alaska, and I felt like going out. Just for the ride, you might say.

HOWARD, barely interested: Don't say.’

WILLY: Oh, yeah, my father lived many years in Alaska. He was an adventurous man. We've got quite a little streak of self-reliance in our family. I thought I'd go out with my older brother and try to locate him, and maybe settle in the North with the old man. And I was almost decided to go, when I met a salesman in the Parker House. His name was Dave Singleman. And he was eighty-four years old, and he’d drummed merchandise in thirty-one states. And old Dave, he’d go up to his room, y’understand, put on his green velvet slippers—I’ll never forget—and pick up his phone and call the buyers, and without ever leaving is room, at the age of eighty-four, he made his living. And when I saw that, I realized that selling was the greatest career a man could want. ’Cause what could be more satisfying than to be able to go, at the age of eighty-four, into twenty or thirty different cities, and pick up a phone, and be remembered and loved and helped by so many different people? Do you know? When he died—and by the way he died the death of a salesman, in his green velvet slippers in the smoker of the New York, New Haven and Hartford, going into Boston—when he died, hundreds of salesmen and buyers were at his funeral. Things were sad on a lotta trains for months after that. He stands up. Howard has not looked at him. In those days there was personality in it, Howard. There was respect, and comradeship, and gratitude in it. Today, it’s all cut and dried, and there’s no chance for bringing friendship to bear—or personality. You see what I mean? They don’t know me anymore.

DEATH OF A SALESMAN opened in 1949 at the Morosco Theater. © Arthur Miller 1949, reprinted with permission.

THE PRICE

The attic of a Manhattan brownstone soon to be torn down.

WALTER: Vic, I wish we could talk for weeks, theres so much I want to tell you . . . . It is not rolling quite the way he would wish and he must pick examples of his new feelings out of the air. I never had friends—-you probably know that. But I do now, I have good friends. He moves, sitting nearer Victor, his enthusiasm flowing. It all happens so gradually. You start out wanting to be the best, and there’s no question that you do need a certain fanaticism; there’s so much to know and so little time. Until you’ve eliminated everything extraneous—-he smiles—-including people. And of course the time comes when you realize that you haven’t merely been specializing in something—-something has been specializing in you. You become a kind of instrument, an instrument that cuts money out of people, or fame out of the world. And it finally makes you stupid. Power can do that. You get to think that because you can frighten people they love you. Even that you love them.—-And the whole thing comes down to fear. One night I found myself in the middle of my living room, dead drunk with a knife in my hand, getting ready to kill my wife.

ESTHER: Good Lord!

WALTER: Oh ya—-and I nearly made it too! He laughs. But there’s one virtue in going nuts—-provided you survive, of course. You get to see the terror—-not the screaming kind, but the slow, daily fear you call ambition, and cautiousness, and piling up the money. And really, what I wanted to tell you for some time now—-is that you helped me to understand that in myself.

VICTOR: Me?

WALTER: Yes. He grins warmly, embarrassed. Because of what you did. I could never understand it, Vic—-after all, you were the better student. And to stay with a job like that through all those years seemed . . . He breaks off momentarily, the uncertainty of Victor’s reception widening his smile. You see, it never dawned on me until I got sick—that you’d made a choice.

VICTOR: A choice, how?

WALTER: You wanted a real life. And that’s an expensive thing; it costs.

THE PRICE opened in 1974 at the Morosco Theater. © Arthur Miller 1968, reprinted with permission.

A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE

A law office.

ALFIERI: Eddie, I want you to listen to me. Pause. You know, sometimes God mixes up the people. We all love somebody, the wife, the kids—-every man’s got somebody that he loves, huh? But sometimes . . . there’s too much. You know? There’s too much, and it goes where it mustn’t. A man works hard, he brings up a child, sometimes it’s a niece, sometimes even a daughter, and he never realizes it, but through the years—-there is too much love for the daughter, there is too much love for the niece. Do you understand what I’m saying to you?

EDDIE, sardonically: What do you mean, I shouldn’t look out for her good?

ALFIERI: Yes, but these things have to end, Eddie, that’s all. The child has to grow up and go away, and the man has to learn to forget. Because after all, Eddie—-what other way can it end? Pause. Let her go. That’s my advice. You did your job, now it’s her life; wish her luck, and let her go. Pause. Will you do that? Because there’s no law, Eddie; make up your mind to it; the law is not interested in this.

EDDIE: You mean to tell me, even if he’s a punk? If he’s—

ALFIERI: There’s nothing you can do.

The one-act version of A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE opened in 1956 at the Coronet Theater; the two-act version also opened in 1956 at London’s Comedy Theater. © Arthur Miller 1955, reprinted with permission.

For the March-April 2001 issue of Humanities magazine, NEH Chairman William R. Ferris spoke with Miller about morality and the public role of the artist.

William R. Ferris: I'd like to begin with Death of a Salesman. In the play Willie Loman's wife says, "He's not the finest character that ever lived, but he's a human being, and a terrible thing is happening to him, so attention must be paid. He's not to be allowed to fall into his grave like an old dog." What kind of attention do you mean?

Arthur Miller: I suppose she was speaking about the care and support that his family might give him, in that context. Of course, there is a larger context, which is social and even political-that a lot of people give a lot of their lives to a company or even the government, and when they are no longer needed, when they are used up, they're tossed aside. I guess that would encompass it.

Ferris: When Death of a Salesman opened in 1949, Brooks Atkinson wrote in his New York Times review that you had written a superb drama. He went on to say, "Mr. Miller has no moral precepts to offer and no solutions of the salesman's problems. He is full of pity, but he brings no piety to it." Is there more of a moral message in Salesman than Atkinson saw there?

Miller: It depends on your vantage point. Willie Loman's situation is even more common now than it was then. A lot of people are eliminated earlier from the productive life in this society than they used to be. I've gotten a number of letters from people who were in pretty good positions at one point or another and then were just peremptorily discarded. If you want to call that a moral area, which I think it is, then he was wrong. What I think he was referring to was that the focus of the play is the humanity of these people rather than coming at them from some a priori political position. I think that is true.

Ferris: So many of your best plays, Death of a Salesman, All My Sons, The Crucible, besides being personal tragedies, are also a commentary on society, similar to Ibsen's work. Do you feel one person's story can transcend itself and speak to all of us?

Miller: I think it depends primarily on the writer's orientation. There is a lot of work being done today which is very sharp, but there doesn't seem to be a moral dimension to them. In other words, they are not looking out beyond the personal story. That is a difficult thing to trace in a work. I suppose if you took Moby-Dick, he could have written that as an adventure story about a whale and hunting it. Instead it became a parable involving man's fate and his struggle for power, over God even. The intensification of a work generally leads in the direction of society if it is indeed intense enough.

Ferris: How do you take daily life and turn it into the stuff of art?

Miller: Well, that's the secret.

Ferris: You're not talking.

Miller: I really don't know the answer to that. It is part of temperament. It is a part of a vision which is only definable through the work of art. You can't start analyzing it into its parts because it falls to pieces.

Ferris: Then what do you think are the core issues that a playwright should deal with?

Miller: There is no prescription that I know of, period. Whatever he feels intensely about and knows a lot about is the core issue for him. If he feels sufficiently about it and is well informed enough about it, factually and psychologically, emotionally, then that's the core issue. You make an issue. The issue isn't there, just lying around waiting to be picked up off the sidewalk. It is what the author is intense about in his life.

Ferris: Would you say there is a process of playwriting that's been a constant since Greek drama, or has this process changed over time?

Miller: You know, the Greeks used to use the same stories, the same mythology, time after time, different authors. There was no premium placed upon an original story--and indeed, Shakespeare likewise. A lot of people wrote plays about great kings. They didn't expect a brand-new story. It was what that new author made of the old story. It is probably the same now. We disguise it by inventing what seem to be new stories, but they're basically the same story anyway.

Ferris: When you wrote Death of a Salesman, how were you trying to take drama and make it new, as Ezra Pound said?

Miller: That play is several inventions which have been pilfered over the years by other writers. It is new in the sense that, first of all, there is very little or no waste. The play begins with its action, and there are no transitions. It is a kind of frontal attack on the conditions of this man's life, without any piddling around with techniques. The basic technique is very straightforward. It is told like a dream. In a dream, we are simply confronted with various loaded symbols, and where one is exhausted, it gives way to another. In Salesman, there is the use of a past in the present. It has been mistakenly called flashbacks, but there are no flashbacks in that play. It is a concurrence of a past with the present, and that's a bit different.

There are numerous other innovations in the play, which were the result of long years of playwriting before that and a dissatisfaction with the way stories were told up to that point.

Ferris: In your recent article in Harper's Magazine, you write about a colorful script doctor called Saul Burry who used to hold court at Whelan's drugstore in New York City. You say that he advised one writer, "You've got too much story. Slow it down. Examine your consequences more. We're in the theater to hear our own hearts beat with brand-new knowledge, not to get surprised by some stupid door slowly opening." Is that Saul Burry or Arthur Miller talking?

Miller: That was Burry. Burry was a very insightful person. He was the best critic I ever encountered, and he was perfectly capable of talking like that. In fact, I wish I could remember more of what he said, but it's so long ago that a lot of it's just slipped away. He had a marvelous way of encapsulating ideas that had to do with playwriting and the theater.

Ferris: What does Saul Burry's advice mean for the audience?

Miller: Pay for the ticket and arrive on time, and nowadays, not to have a cell phone go off. He expected the audience to cooperate and to appreciate what was in front of him as best he could. He also, I would have thought, probably wanted them to educate themselves so that they were less inclined toward what was specious and stupid.

Ferris: In many of your plays, from Willie and Biff, Joe and Chris Keller, to Victor Frank and his father's memory in The Price, fathers and sons are a theme. You grew up during the Depression and you've said that you witnessed a lot of grown men lose themselves when they lost their jobs. You've also said your relationship with your own father was "like two searchlights on different islands." How has what you saw during the Depression influenced your work?

Miller: Fundamentally, it left me with the feeling that the economic system is subject to instant collapse at any particular moment--I still think so--and that security is an illusion which some people are fortunate enough not to outlive. On the long run, after all, we've had these crises--I don't know how many times in the last hundred years--not only we but every country. What one lived through in that case was for America a very unusual collapse in its depth and its breadth. A friend of mine once said that there were only two truly national events in the history of the United States. One was the Civil War and the other one was the Depression.

Ferris: I think that's so true.

Miller: It leaves one with a feeling of expectation that the thing can go down, but also with a certain pleasure, that it hadn't gone down yet.

Ferris: What is it about father-son relationships that provides such good material?

Miller: The two greatest plays ever written were Hamlet and Oedipus Rex, and they're both about father-son relationships, you know. So this goes back.

Ferris: It is nothing new.

Miller: It is absolutely nothing new. This is an old story. I didn't invent it and I'm sure it will happen again and again.

Ferris: Three plays are usually named as the great works of the early twentieth century--your Death of a Salesman, Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night, and Tennessee Williams's A Streetcar Named Desire. I heard that after you saw Streetcar, you rewrote the play you were working on at the time, Inside of His Head, and that turned into Death of a Salesman. What did you see in Streetcar that changed your vision of your own play?

Miller: Actually, Salesman was practically written by the time I saw Streetcar. What it did was to validate the use of language the way Salesman uses language. People have forgotten that, thank God, that Willie Loman isn't talking street talk; Willie Loman's talk is very formed and formal, very often. It's almost Victorian. That was the decision I made: to lift him into the area where one could deal with his ideas and his feelings and make them applicable to the whole human race. I'm using slang in the play and different kinds of speech, but it is basically a formed, very aware use of the English language. Of course, Tennessee was similarly a fundamentally formal writer, and he was not trying to write the way people speak on the street. So it had a relationship.

Ferris: What about O'Neill? Did he influence your work? Did other playwrights?

Miller: He really didn't. When I started seriously writing in the late forties, he had come to a hiatus in his writing. He hadn't been writing or hadn't at least been producing or publishing plays for some years. His vantage point was basically religious rather than personal at that time. I'm speaking now of the late thirties and up to the end of the forties and early fifties. What certainly was a force was his dedication and his integrity. Those were maybe more important than anything else because I don't have to tell you that the spirit of Broadway is always vulgar, it's always a show shop, it's always the same thing. It never changes. To try to impose upon it something with a longer vision is very difficult. These plays usually fail the first time around and are rejected, if not worse. You need strong teeth and to hold on like a bulldog, and that was a great example.

Ferris: Is there something coming out of theater right now that is setting standards the way those three plays did in their day?

Miller: If there is, I don't know about it. I don't go to the theater all that much, but I do go where there seems to be something of value. I'm not aware of anything at the moment, but that doesn't mean there isn't. It's simply I don't see enough to make an overall judgment.

Ferris: In our society of sound bites and short attention spans, is theater anachronistic?

Miller: Not at all, not at all. No, it isn't by any means. Quite obviously, there is an enormous audience still there. For all I know, it's bigger than it's been in the past years. Death of a Salesman just finished a national tour, and there was no problem getting an audience. There is a problem on the so-called commercial stage in New York, of course. The price of a ticket is exorbitant, and there are no longer original productions possible, apparently, on the commercial stage. They are all plays that were taken from either England or smaller theaters, off-Broadway theaters, and so on. The one justification there used to be for the commercial theater was that it originated everything we had, and now it originates nothing. But the powers that be seem perfectly content to have it that way. They don't risk anything anymore, and they simply pick off the cream. It leaves most theater at the mercy of the market, and that doesn't always reflect what's valuable. So, there you are.

Ferris: What would you like to see in theater today?

Miller: Good stuff. There is no definition for these things. Theater is a very changeable art. It responds to the moment in history the way the newspaper does, and there's no predicting what to come up with next.

Ferris: In your life, you've often taken a very visible stand for what you believe in, whether it was refusing to name names at the House Un-American Activities Committee or doing advocacy against censorship. What is the artist's role in political life?

Miller: I would hope that he would just be a good--if I may use that corny old phrase--a good citizen. People do look to others for some leadership, and it's not bad for them to supply it when they feel that way. I wouldn't lay it down as a rule that an artist has to do anything he doesn't feel like doing, but sometimes there are issues. For example, censorship is of immediate importance to us. They should be taking positions on that and any number of issues that are very close to us, for example, whether or not the humanities are financed, and financed sufficiently, and how they are administered. All that is political policy, but it certainly affects the arts.

Ferris: Do you see a public life having an impact on your creative life?

Miller: In a way, sure. You gain a lot of different kinds of experience that way, and it's not bad to take a cold bath in a public pool occasionally. It's hard to trace it, but you become more and more aware of what things mean to people.

Ferris: When you took Death of a Salesman to China in 1983, were there any surprises?

Miller: There were a number. I wrote a book called The Salesman in Beijing, a daily diary of what was happening during the course of that production.

Ferris: The cultures seem so different, one wonders how Chinese audiences reacted to what seems to be a very American story.

Miller: It is an American story, but its applications are pretty wide. It doesn't really matter where it's played. Of course, it's not played as much as The Crucible. But it's played enough around the world, and it doesn't seem to matter where it is.

Ferris: Although Death of a Salesman got rave reviews the first night, that was not so with The Crucible, though it went on to great success around the world. You write about colleagues walking out of the theater the night The Crucible was premiered and not even speaking to you. What was it like to witness that?

Miller: It was very discouraging. At the same time, I felt a certain happiness that the play had dealt with the issue that everybody was worried about privately, and that I had brought it to the surface. There is an old rule of psychology that if something doesn't meet resistance, it is probably not true.

I knew The Crucible was what it was. I withstood the coldness at the moment, but it certainly wasn't comfortable. But I have the ability to slough things off when they get too tough.

Ferris: I want to thank you for taking the time from your writing to do this interview. It has been a pleasure talking with you.

Miller: Thank you.

On Politics and the Art of Acting

BY ARTHUR MILLER

The 30th Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities

March 26, 2001

Here are some observations about politicians as actors. Since some of my best friends are actors I don't dare say anything bad about the art itself. The fact is that acting is inevitable as soon as we walk out our front doors into society; I am acting now; certainly I am not speaking in the same tone as I would in my living room. It is no news that we are moved more by our glandular reactions to a leader's personality, his acting, than by his proposals or his moral character. To their millions of followers, after all, many of them highly intelligent university intellectuals, Hitler and Stalin were profoundly moral men, revealers of new truths. Aristotle thought man was by nature a social animal, and in fact we are ruled more by the arts of performance, by acting in other words, than anybody wants to think about for very long.

But in our time television has created a quantitative change in all this; one of the oddest things about millions of lives now is that ordinary individuals, as never before in human history, are so surrounded by acting. Twenty four hours a day everything seen on the tube is either acted or conducted by actors in the shape of news anchor men and women, including their hairdos. It may be that the most impressionable form of experience now, for many if not most people, consists of their emotional transactions with actors which happen far more of the time than with real people. For years now commentators have had lots of fun with Reagan's inability to distinguish movies he had seen from actual events in which he had participated, but in this as in so much else he was representative of a common perplexity when so much of a person's experience comes at him through the acting art. In other periods, a person might confront the arts of performance once a year in a church ceremony or a rare appearance by a costumed prince or king and their ritualistic gestures; it would have seemed a very strange idea that ordinary folk would be so subjected every day to the persuasions of professionals whose studied technique, after all, is to assume the character of someone who is not them.

Is this persistent experience of any importance? I can't imagine how to prove this, but it seems to me that when one is surrounded by such a roiling mass of consciously contrived performances it gets harder and harder for a lot of people to locate reality anymore. Admittedly, we live in an age of entertainment, but is it a good thing that our political life, for one, be so profoundly governed by the modes of theatre, from tragedy to vaudeville to farce? I find myself speculating whether the relentless daily diet of crafted, acted emotions and canned ideas is not subtlely pressing our brains to not only mistake fantasy for what is real but to absorb this process into our personal sensory process. This last election is an example. Obviously we must get on with life, but apparently we are now called upon to act as though nothing very unusual has happened and that nothing in our democratic process deteriorated, as for instance our claim to the right to instruct lesser countries on how to conduct fair elections. So in a subtle way we are induced to become actors too. The show, after all, has to go on, even if the audience is obliged to join in the acting.

Political leaders everywhere have come to understand that to govern they must learn how to act. No differently than any actor Gore went through several changes of costume before finding the right mix to express the personality he wished to project. Up to the campaign he seemed an essentially serious type with no great claim to humor, but the Presidential type character he had chosen to play was apparently happy, upbeat, with a kind of Bing Crosby mellowness. I daresay that if he seemed so awkward it was partly because the image was not really his, he had cast himself in a role that was wrong for him. As for Bush, now that he is President he seems to have learned not to sneer quite so much, and to cease furtively glancing left and right when leading up to a punch line, followed by a sharp nod to flash that he has successfully delivered it. This is bad acting because all this dire over-emphasis casts doubt on the text. Obviously, as the sparkly magic veil of actual power has descended upon him he has become more relaxed and confident, like an actor after he has read some hit reviews and knows the show is in for a run.

At this point I suppose I should add something about my own bias. I recall the day, back in the Fifties, during Eisenhower's campaign against Adlai Stevenson when I turned on my television and saw the General who had led the greatest invasion force in history, lying back under the hands of a professional makeup woman preparing him for his TV appearance. I was far more naive then, and so I still found it hard to believe that henceforth we were to be wooed and won by rouge, lipstick and powder rather than ideas and positions on public issues. It was almost as though he was getting ready to go on in the role of General Eisenhower instead of simply being him. In politics, of course, what you see is rarely what you get, but in fact Eisenhower was not a good actor, especially when he ad-libbed, disserving himself as a nearly comical bumbler with the English language when in fact he was actually a lot more literate and sophisticated than his fumbling public speaking style suggested. As his biographer, a Time editor named Hughes, once told me, Colonel Eisenhower was the author of all those smoothly liquid, rather Roman-style speeches that had made his boss, Douglas MacArthur, so famous. Then again, I wonder if Eisenhower's syntactical stumbling in public made him seem more convincingly sincere.

Watching some of our leaders on TV has made me wonder if we really have any idea what is involved in the actor's art, and I recall again a story once told me by my old friend, the late Robert Lewis, director of a number of beautiful Broadway productions, including the original "Finian's Rainbow." Starting out as an actor in the late Thirties, Bobby had been the assistant and dresser of Jacob Ben Ami, a star in Europe and in New York as well. Ben Ami, an extraordinary actor, was playing in a Yiddish play but despite the language and the location of the theatre far from Times Square on the lower East Side of Manhattan, one of its scenes had turned it into a substantial hit with English-speaking audiences. Experiencing that scene had become the in-thing to do in New York. People who had never dreamed of seeing a Yiddish play travelled downtown to watch this one scene, and then left. In it Ben Ami stood at the edge of the stage staring into space, and with tremendous tension, brought a revolver to his head. Seconds passed, whole minutes, some in the audience shut their eyes or turned away certain the shot was coming at any instant. Ben Ami clenched his jaws, sweat broke out on his face, his eyes seemed about to pop out of his head, his hands trembled as he strove to will himself to suicide; more moments passed, people in the audience were gasping for breath and making strange asphyxiated noises; finally, standing on his toes now as though to leap into the unknown, Ben Ami dropped the gun and cried out, Ich kann es nicht!" I can't do it! Night after night he brought the house down; Ben Ami had somehow literally compelled the audience to suspend its disbelief and to imagine his brains splattered all over the stage.

Lewis, aspiring young actor that he was, begged Ben Ami to tell him the secret of how he had created this emotional reality, but the actor kept putting him off, saying he would only tell him after the final performance. "It's better for people not to know," he said, "or it'll spoil the show."

Then at last the final performance came and at its end Ben Ami sat in his dressing room with the young Lewis.

"You promised to tell me," Lewis said.

"All right, I'll tell you. My problem with this scene," Ben Ami explained, "was that I personally could never blow my brains out, I am just not suicidal, and I can't imagine ending my life. So I could never really know how that man was feeling and I could never play such a person authentically. For weeks I went around trying to think of some parallel in my own life that I could draw on. What situation could I be in where first of all I am standing up, I am alone, I am looking straight ahead, and something I feel I must do is making me absolutely terrified, and finally that whatever it is I can't do it?"

"Yes," Lewis said, hungry for this great actor's cue to greatness. "And what is that?"

"Well," Ben Ami said, "I finally realized that the one thing I hate worse than anything is washing in cold water. So what I'm really doing with that gun to my head is, I'm trying to get myself to step into an ice cold shower."

Now if we transfer this situation to political campaigns -- who are we really voting for -- the self-possessed character who projects dignity, exemplary morals and forthright courage enough to lead us in war or depression, or is he simply good at characterizing a counterfeit with the help of professional coaching, executive tailoring, and that whole armory of pretense which the grooming of the president can now employ? Are we allowed anymore to know what is going on not in the candidate's facial expression and his choice of suit, but in his head? Unfortunately, as with Ben Ami, this is something we are not told until he is securely in office and his auditioning ends. After spending tens of million of dollars both candidates -- at least for me -- never managed to create that unmistakable click of recognition as to who they really were. But maybe this is asking too much. As with most actors, maybe any resemblance between them and their roles is purely accidental.

The so-called Stanislavsky System came into vogue at the dawn of the 20th Century when science was recognized as the dominating force of the age. Objective scientific analysis promised to open everything to human control and the Stanislaveky method was an attempt to systematize the actor's vagrant search for authenticity as he seeks to portray a character different from his own. Politicians do something similar all the time; by assuming personalities not genuinely their own -- let's say six-pack, lunch box types -- they hope to connect with ordinary Americans. The difficulty for Bush and Gore in their attempts to seem like regular fellas, was that both were scions of successful and powerful families. Worse yet for their regular fella personae, both were in effect created by the culture of Washington, D.C. and you can't hope to be President without running against Washington. The problem for Gore was that Washington meant Clinton whom he dared not acknowledge lest he be morally challenged; and as for Bush, he could only impersonate an outsider pitching against dependency on the Federal Government whose payroll, however, had helped feed two generations of his family. There's a name for this sort of cannonading of Washington, it is called acting. To some important degree both gentlemen had to act themselves out of their real personae into freshly begotten ones. The reality, of course, was that the closest thing to a man of the people was Clinton-the-unclean, the real goods with the six-pack background who it was both dangerous and necessary to disown. This took a monstrous amount of acting.

It was in the so-called debates that the sense of a contrived performance rather than a naked clash of personalities and ideas came to a sort of head. Here was acting, acting with a vengeance But the consensus seems to have called the performances decidedly boring. And how could it be otherwise when both men seemed to be attempting to display the same genial temperament a readiness to perform the same role and in effect to climb into the same warm suit? The role, of course, was that of the nice guy, the mildness was all, Bing Crosby with a sprinkling of Bob Hope. Clearly they had both been coached to not threaten the audience with too much passion, but rather to reassure that if elected they would not disturb any reasonable person's sleep. In acting terms there was no inner reality, no genuineness, no glimpse into their unruly souls. One remarkable thing did happen, though -- that single split second shot which revealed Gore shaking his head in helpless disbelief at some inanity Bush had spoken; significantly, this gesture earned him many bad press reviews for what was called his superior airs, his sneering disrespect -- in short, he had stepped out of costume and revealed his reality. This, in effect,was condemned as a failure of acting. The American press is made up of disguised theatre critics; substance counts for next to nothing compared to style and inventive characterization. For a millisecond Gore had been inept enough to have gotten real! And this clown wanted to be President yet! Not only is all the world a stage, but we have all but obliterated the fine line between the feigned and the real.

But was there ever such a border? It is hard to know, but we might try to visualize the Lincoln-Douglas debates before the Civil War when thousands would stand, spread out across some pasture to listen to the two speakers mounted on stumps so they could be seen from far off. There certainly was no makeup; neither man had a speech writer but, incredibly enough, made it all up himself. In fact, years later Lincoln wrote the Gettysburg Address on scraps of paper on his way to a memorial meeting. Is it imaginable that any of our candidates could have such conviction, and more importantly such self-assured candor as to move him to pour out his heart this way? To be sure, Lincoln and Douglas, at least in the record of their remarks, were civil to one another, but the attack on each other's ideas was sharp and thorough, revealing of their actual approaches to the nation's problems. As for their styles, they had to have been very different than the current laid-back cool before the lense. The lense magnifies everything; the slight lift of an eyelid and you look like you're glaring. If there is a single most basic requirement for success on television it is minimalization; to be convincing before the camera is that whatever you are doing do it less and emit cool. In other words -- act. In contrast, speakers facing hundreds of people without a microphone and in the open air, must inevitably have been broader in gesture and even more emphatic in speech than in life. Likewise, their use of language had to be more pointed and precise in order to carry their points out to the edges of the crowd. And no makeup artist stood waiting to pounce on every bead of sweat on a speaker's lip; the candidates were stripped to their shirtsleeves in the summer heat and people nearby could no doubt smell them. There may, in short, have been some aspect of human reality in such a debate.

Given the camera's tendency to exaggerate any movement, it may in itself have a dampening effect on spontaneity and conflict. There were times in this last campaign when one even wondered if the candidates feared that to really raise issues and engage in a genuine clash before the camera, might dangerously set fire to some of the more flammable public. But of course there is a veritable plague of benign smiling on the glass screen, quite as if a revealing scowl or passionate outburst might ignite some kind of social conflagration.